The official version of this document can be found via the PDF button.

The below content has been automatically generated from the original PDF and some formatting may have been lost, therefore it should not be relied upon to extract citations or propose amendments.

Title of consultation:

Title of consultation:

Review of legislation on harmful electronic communications

Summary:

The purpose of this consultation is to invite comments on the legislation applying to harmful electronic communications. It seeks views on whether the existing legislation is appropriate, or whether it requires amending, to remove any doubt about its application and to ensure that it is future proof'. It also considers whether a new offence is required to tackle the publication of revenge pornography.

Date published: Closing date:

31 March 2015 19 June 2015

Supporting documents attached:

Annex 1: Electronic Communications - Usage & Behaviour Survey November 2013

We aim for a full and open consultation process and aim to publish consultation submissions online. If you do not want your response, including your name and contact details, to be published, please state this clearly in writing when you submit your response together with a brief explanation. We will respect your wish for confidentiality as far as possible, subject to the Freedom of Information law.

The Council of Ministers is consulting on whether it is appropriate to make changes to the legislation applying to harmful electronic communications.

The Council recognises that it is important that the relevant authorities in Jersey have the ability, in appropriate cases, to prosecute people for sending grossly offensive, threatening, false or malicious electronic communications, including via social media. As part of this, the law should enable the appropriate authorities to tackle behaviour that constitutes cyberbullying; however, the law should not provide that electronic communications are subject to a more stringent level of legislation than other means of communication.

The Council is confident that the existing legislation is largely fit for purpose. However, changes to legislation may be required to remove any doubt about the application of existing legislation to activities conducted electronically, via means such as social media; to make certain that the legislation is future proof; and to ensure that existing offences do not have a chilling effect on free speech.

For the purposes of this consultation, the term social media has been broadly defined as meaning the online social networks, technology and methods through which people share content, opinions, information and ideas – whether this is in the form of text, images, audio or video' though it is worth noting that this definition should not be taken as exhaustive.[1]

Cyberbullying may include a range of online conduct and has been defined as the use of information and communication technologies to support deliberate, repeated, and hostile behaviour by an individual or group that is intended to harm others.' [2] So it may include sending abusive or threatening messages, but may also take place by other methods, such as impersonating a person online or posting revenge pornography.

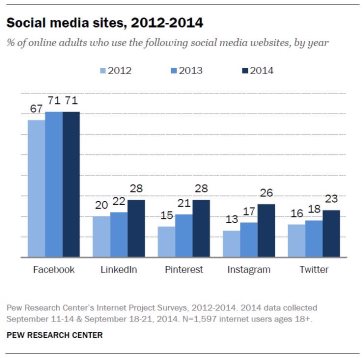

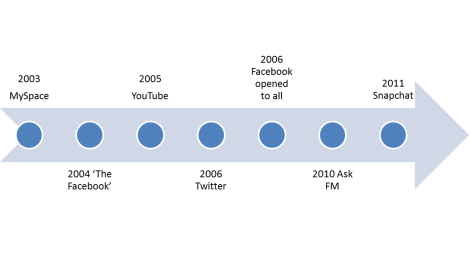

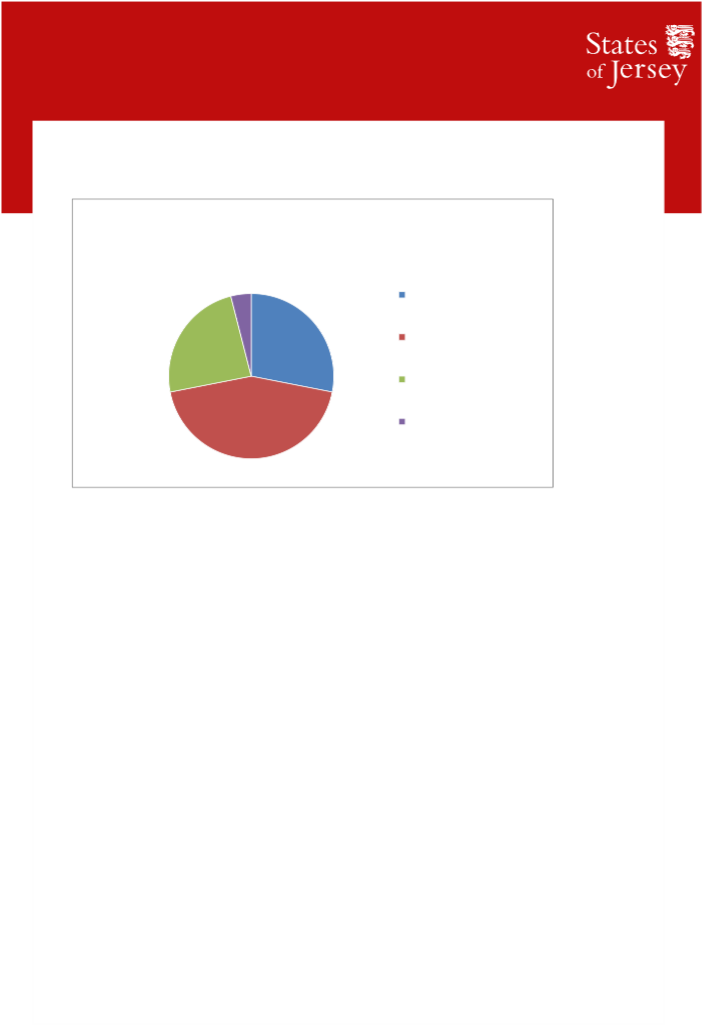

The digital world moves extremely quickly and any legislation in this area runs the risk of quickly becoming outdated. From Snapchat to real-time web', new platforms and trends are emerging at an unprecedented rate, in an often unpredictable way and on a grand scale. Taking Facebook as an example, it was founded in 2004

and now boasts more than 1.3 billion active users.[3] Other platforms, claiming fewer users are growing at a faster rate, as indicated in

Figure 1: Social media sites, 2012-2014.[4] Therefore, it is proposed that any amendments to the law and any new offences should be drafted in such a manner that makes them resilient to technological development, or future proof', as far as it is practical to do so.

Figure 1: Social media sites, 2012-2014.[4] Therefore, it is proposed that any amendments to the law and any new offences should be drafted in such a manner that makes them resilient to technological development, or future proof', as far as it is practical to do so.

Figure 1: Social media sites, 2012-2014

It is also vital that any amendments to the law should be made in such a way that strikes a balance between ensuring criminal law can be implemented effectively and protecting freedom of expression. As definitions of grossly offensive' or threatening' communications can be subjective, consideration must be given to how legislation can be framed so as to avoid unnecessarily infringing the right to freedom of expression, as provided by Article 10 of the European Convention of Human Rights, while also ensuring that there is greater certainty in the application of the relevant provisions than has been the case in other jurisdictions, in particular England and Wales.

This consultation is not about the detail of potential amendments to the law but about the proposed approach and the high-level principles that will guide any legislative response.

This consultation is not about the detail of potential amendments to the law but about the proposed approach and the high-level principles that will guide any legislative response.

Contents

- Background

- Current legislative position

- International examples

- Islanders' experiences and attitudes

- Proposal

- Conclusion and questions for consultation

Who should respond?

It is important that any changes to legislation take into account a wide range of views and experiences. Therefore we would like to hear from:

- members of the public;

- telecoms providers;

- ISPs;

- social media providers;

- digital businesses;

- internet safety professionals;

- consumer organisations; and

- schools and other education providers.

The internet has become integral to everyday life in Jersey. By 2014, nine out of ten adults (91%) had access to the internet; 89% of adults could access it at home and 86% of workers could access the internet at work.[5]

Although the most popular device for accessing the internet in Jersey remains the home computer, it is followed closely by the smart phone. The use of tablets is also increasing in popularity. In 2013 more than half (59%) of those in Jersey who accessed the internet used a smart phone, while more than two-fifths (42%) used a tablet.[6] In the UK there has also been a rise in the number of internet-enabled devices such as televisions and games consoles, which one would expect to see mirrored in Jersey.[7]

Internationally, there has been a rapid rise in the use of social networks. In the UK almost half of adults (47%) claim to use a social network, and usage is even higher in Jersey.[8] In 2014, 65% of adults said they used a social networking site. The use of social networks is particularly prevalent among young people; nine out of ten adults aged 16-34 years (92%) reported using social media such as Twitter and Facebook, compared to two out of ten (19%) of those aged 65 years or over.[9]

In conjunction with increased access to the internet and the rapid growth in the use of social media, there have been growing concerns, both internationally and in Jersey, about the potential for harm caused by new types of activity associated with their use.

UK case studies

Internationally, there have been numerous high profile cases involving cyberbullying and other abusive and threatening behaviour conducted over social media. These have involved a variety of social networking sites including Twitter, Facebook and Ask.Fm. In some instances criminal charges have been brought against alleged offenders.

Internationally, there have been numerous high profile cases involving cyberbullying and other abusive and threatening behaviour conducted over social media. These have involved a variety of social networking sites including Twitter, Facebook and Ask.Fm. In some instances criminal charges have been brought against alleged offenders.

The box below shows some examples of recent UK cases. These illustrate the range of activity that is being considered in this consultation.

Figure 2: UK Case Studies

Abusive and menacing tweets

In January 2014 Isabella Sorley and John Nimmo were sentenced to twelve weeks and eight weeks respectively for sending abusive tweets to the feminist campaigner Caroline Criado-Perez. They pled guilty to separate offences of improper use of a public electronic communications network, contrary to section 127 of the Communications Act 2003.

Offensive Facebook posts

In 2012 Matthew Woods, who had made several offensive postings about the missing five- year-old girl April Jones, was jailed for twelve weeks. He had been found guilty of sending by means of a public electronic communications network a message or other matter that is grossly offensive, contrary to the Communications Act 2003.

In 2012 Liam Stacey posted offensive comments about the footballer Fabrice Muamba. He pleaded guilty to a racially aggravated offence under Section 4A of the Public Order Act 1986 and he was sentenced to 56 days in prison.

Cyberbullying

The suicide of teenager Hannah Smith is believed to have occurred after she was subjected to bullying on the social networking site Ask.Fm. Following this the site made changes to its reporting policies.

Revenge pornography

In 2014 Luke King was given a 12-week sentence after pleading guilty to harassment without violence. He had published intimate images of a woman on the WhatsApp messaging service, after making a series of threats to her. This is believed to be the first instance in the UK of someone being jailed for posting revenge pornography online, following the issuance in October 2014 of guidance that clarifies how prosecutors can use existing legislation to prosecute perpetrators of these offences. King was prosecuted under the Protection from Harassment Act 1997, but people who distribute revenge pornography images and videos could now face two years in jail under a new UK law dealing specifically with the practice. The Criminal Justice and Courts Act covers material shared via the internet, text messages and physical distribution.

All of the major social networking sites have policies that are designed to help safeguard users. Details of these policies can be found on the social networks' websites.[10]

In most instances the policies prohibit abusive behaviour including: threats to others, bullying and harassment, and hate speech. The policies also outline the steps users should take if they encounter this type of behaviour. A recent report on social media and criminal offences by the House of Lords Select Committee on Communications noted:

Facebook has a real name culture, a set of community standards (e.g. regarding nudity), enables people to control their own privacy, and enables the reporting of abuse; Twitter have rules against threats of violence, targeted harassment and similar issues. Other operators are less responsible.[11]

However, in some instances, social media policies have been seen to be ineffective or the social networks themselves have not been seen to enforce these policies adequately. Internationally, concerns have been expressed that these policies alone are not sufficient to protect people from harmful behaviour that would be illegal if conducted offline. The Select Committee report goes on:

The number of staff employed to consider reports of content or conduct is inevitably inadequate to the scale of use of the website. Globally, Facebook employ "hundreds" of people in this area; Twitter "in excess of 100" We encourage website operators further to develop their ability to monitor the use made of their services. In particular, it would be desirable for website operators to explore developing systems capable of preventing harassment, for example by the more effective real-time monitoring of traffic.[12]

This sentiment was echoed in comments from Twitter CEO Dick Costolo in a recent interview:

We're going to get a lot more aggressive about [abuse on the platform] and

it's going to start right nowwe've always taken it seriously. We've drawn a line on what constitutes harassment and abuse. I believe that we haven't yet drawn that line to put the cost of dealing with harassment on those doing the harassing. It shouldn't be the person who's being harassed who has to do a lot of workyou set policies and then you try to stick to those policies.[13]

it's going to start right nowwe've always taken it seriously. We've drawn a line on what constitutes harassment and abuse. I believe that we haven't yet drawn that line to put the cost of dealing with harassment on those doing the harassing. It shouldn't be the person who's being harassed who has to do a lot of workyou set policies and then you try to stick to those policies.[13]

It is of particular importance to the Government of Jersey that vulnerable users (including children) are protected against harmful behaviour when using social networking sites.

Section 2: Current legislative position Existing legislation

There are four key pieces of legislation that are relevant to this area in Jersey. These are:

- Electronic Communications (Jersey) Law 2000[14]

- Article 51 of the Telecommunications (Jersey) Law 2002[15]

- Crime (Disorderly Conduct and Harassment) (Jersey) Law 2008[16]

- Data Protection (Jersey) Law 2005[17]

This legislation was enacted before social media became pervasive, and thus was not designed for the digital era', or was not explicitly intended to deal with behaviour conducted via social media.

Figure 3: Launch dates of major social networks and video sharing sites

It is important therefore, that this consultation establishes whether it is necessary to make changes to existing legislation, to ensure that the relevant authorities can adequately respond to criminal behaviour – such as sending grossly offensive, threatening, false or malicious communications via social media – while also ensuring that the offences do not have a chilling effect on free speech.

It is important therefore, that this consultation establishes whether it is necessary to make changes to existing legislation, to ensure that the relevant authorities can adequately respond to criminal behaviour – such as sending grossly offensive, threatening, false or malicious communications via social media – while also ensuring that the offences do not have a chilling effect on free speech.

The relevant Jersey legislation is summarised below. Electronic Communications (Jersey) Law 2000 [ECJL]

The ECJL provides for the facilitation of electronic business and the use of electronic communications and electronic storage. Under the ECJL, provision is made for the obligations of service providers and for the protection of service providers from criminal and civil liability, in certain circumstances, for messages posted on their systems. The term electronic communication' is defined in section 2 of the ECJL as follows:

electronic communication' means a communication of information transmitted –

- by means of guided or unguided electromagnetic energy or of both; or

- by other means but while in electronic form;

However, no provision is made in the ECJL for the prohibition of grossly offensive, threatening or malicious communications.

Article 51 of the Telecommunications (Jersey) Law [TJL] Under Article 51, any person who –

- sends, by means of a public telecommunication system, a message or other matter that is grossly offensive or of an indecent, obscene or menacing character; or

- for the purpose of causing annoyance, inconvenience or needless anxiety to another, sends by those means a message that the person knows to be false or persistently makes use for that purpose of a public telecommunication system,

shall be guilty of an offence and liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 6 months or to a fine not exceeding level 4 (currently £5,000) on the standard scale, or both.

The TJL defines telecommunication system' as a system for the conveyance of messages through the agency of energy'.

[18] It is clear that abusive phone calls can be prosecuted under Article 51 of the TJL. It also appears that emails and postings on video sharing sites such as YouTube, or social media sites such as Facebook and Twitter, can be prosecuted under Article 51, because internet access is provided via a public telecommunications system.

[18] It is clear that abusive phone calls can be prosecuted under Article 51 of the TJL. It also appears that emails and postings on video sharing sites such as YouTube, or social media sites such as Facebook and Twitter, can be prosecuted under Article 51, because internet access is provided via a public telecommunications system.

Decisions of the Courts in England and Wales have made it clear that messages sent via social media were communications through such a service.[19] The definition of telecommunications system' in the TJL is different to that used in similar legislation in England and Wales however, which refers to an electronic communications service'.[20] Though it is perhaps not beyond doubt, it is likely that the TJL would be interpreted in a similar way with regard to the applicability of Article 51 to electronic communications and communications via social media.

Crime (Disorderly Conduct and Harassment) (Jersey) Law, 2008 [CDCJL] Under Article 2 of the CDCJL a person commits an offence if he or she:

- uses words that are threatening or abusive;

- behaves in a threatening or abusive way; or

- engages in disorderly behaviour,

within the hearing or sight of another person likely to be caused alarm or distress by the words or behaviour. As a consequence this offence does not apply in the context of electronic communications.

However, Article 3 of the CDCJL provides that a person commits an offence if he or she pursues a course of conduct:

- that amounts to harassment of another person; and

- that he or she knows, or ought to know, amounts to harassment of another person.

Under some circumstances the CDCJL would be the appropriate legislation for dealing with the conduct being considered in this consultation. However, this would

only be the case when there have been two or more separate incidents such that a course of conduct' can be established.[21]

only be the case when there have been two or more separate incidents such that a course of conduct' can be established.[21]

The application of the Article 3 offence in the context of communications via social media was considered by the Royal Court in the case of Chapman v Attorney General, which concerned an appeal against conviction and sentence from the Magistrate's court.[22] In that case the course of conduct alleged to amount to harassment arose from three incidents, two of which were communications on Facebook. Although in that case the Royal Court did not find the messages sufficiently serious to justify criminal culpability for the course of conduct as whole, it is clear that the offence can be used in relation to communications via social media.

The Data Protection (Jersey) Law 2005 [DPL]

The DPL requires data controllers' to process personal data (i.e. data relating to particular identifiable persons) in accordance with eight data protection principles as well as the other provisions of the DPL.[23]

In many cases the processing of personal data by private individuals for domestic purposes using social media will fall within an exemption from the requirements of the DPL. As a result, the DPL does not provide a complete answer to the concerns addressed in this consultation.[24] However, in the UK, equivalent provisions of the Data Protection Act 1998 have been used occasionally to address the unwanted publication of some personal data on social media by campaign groups.[25]

Summary

Summary

In summary, analysis of the existing legislation indicates the following:

- No explicit provision is made in the ECJL for the prohibition of offensive, threatening or malicious communications.

- It appears that the definition of telecommunications systems' in the TJL could be interpreted as including electronic communications such as email and social media, so that the offences in Article 51 of that law could be applied to harmful online communication such as cyberbullying.

- Prosecution under the CDCJL is appropriate in some cases when there have been sufficient incidents to qualify as a course of conduct'. However, one-off' incidents would not qualify as harassment.

- The DPL places some relevant restrictions on the use of personal data, but it is limited in its application to the processing of personal data by private individuals, so it isn't a substitute for appropriately tailored offences.

- The existing law does provide protection from cyberbullying and other types of behaviour on social media that would be considered criminal if conducted via traditional means of communication.

- Nonetheless, consideration should be given as to whether the TJL or other legal provisions should be amended or additional offences introduced to remove any ambiguity about the circumstances in which a prosecution may take place and the particular types of malicious, grossly offensive and threatening communications that are covered.

Section 3: International examples

Internationally, the type of behaviour considered in this consultation is rarely a specific criminal offence. Instead, it often falls under other legislation such as stalking and harassment laws.

Some jurisdictions have taken steps to explicitly tackle behaviour such as cyberbullying through legislation.

Canada

For example, in 2013 Nova Scotia introduced a new law (the Cyber Safety Act) which gives victims the ability to sue cyberbullies or (in the case of minors) their parents. The legislation allows victims to apply for protection orders to place restrictions on, or to identify, the cyberbully. A new unit, Cyber Scan, oversees this law.[26] The court has powers to cut off the suspected bully's internet or seize their equipment for up to one year. This legislation has been criticised as it is perceived that those deemed to be cyberbullies' are not offered the opportunity of a defence and that parents and school administrators can be liable, to various degrees, for what minors do online.

USA

In the USA the primary federal law regarding internet safety is the Children's Internet Protection Act of 2000 [CIPA]. Schools and libraries subject to the CIPA must have an internet safety policy for their computers that filters and blocks obscene content in order to receive discounts for internet through their E-rate programme. They must also have a policy that addresses minors' access to harmful material on the internet.

Individual US states have also passed some relevant legislation. For example, in 2010 Arkansas passed a new criminal offence of cyberbullying that criminalises the transmission, sending or posting of a communication by electronic means of frightening, coercing, intimidating, threatening, abusing, harassing or alarming another person if this action was in furtherance of severe, repeated or hostile behaviour towards the other person. This offence is punishable by up to 90 days imprisonment.

Singapore

Singapore

In November 2014 Singapore introduced a wide-ranging law that targets harassment.[27] The law makes it clear that the courts may prosecute acts of harassment committed online. The courts will also be able to impose fines of up to $5000, longer imprisonment sentences (up to 12 months), community orders and increased penalties for repeat offenders.

England and Wales

In England and Wales the behaviour being considered in this consultation falls foul of offences under a number of different pieces of legislation. The two most relevant are: the Malicious Communications Act 1998 and the Communications Act 2003.

Section 1 of the Malicious Communications Act 1998

The Malicious Communications Act encompasses the sending of letters, electronic communications and other articles to another person. It covers messages that are indecent, grossly offensive, constitute a threat and that contain false information. To commit the offence the person sending the communication must intend to cause distress or anxiety to the recipient or to other people whom the sender intends the message to be communicated. By virtue of section 1(2A) of the Act, the offence has been specifically extended to cover any communication in electronic form.

Section 127 of the Communications Act 2003

By virtue of Section 127(1) of the Communications Act 2003, it is an offence for a person to send or cause to be sent through a public electronic communications network', a message or other matter that is grossly offensive or of an indecent, obscene or menacing character'. Section 127(2) goes on to provide that it is an offence to send or cause to be sent a false message for the purpose of causing annoyance inconvenience or needless anxiety to another'. These offences are similar to those in the TJL.

As noted earlier in this paper, there is a distinction between the Communications Act 2003 and the TJL in the terminology used to describe a system through which messages are sent. However, it is likely that, as with the English legislation, the TJL can capture all forms of electronic communication, including those sent via social media.

However, the practical application of the Communications Act 2003, which like the TJL was enacted before the mass adoption of social media, also reveals some difficulties with the application of the section 127 offences to behaviour on social media

and offers some important lessons. Indeed, it is only recently that its application to social media has been clarified by judgments of the courts and by the introduction in 2013 of new Guidelines for prosecutions involving social media by the then Director of Public Prosecutions.[28]

and offers some important lessons. Indeed, it is only recently that its application to social media has been clarified by judgments of the courts and by the introduction in 2013 of new Guidelines for prosecutions involving social media by the then Director of Public Prosecutions.[28]

One particular problem that was noted with section 127(1) of the Communications Act 2003 is that it does not make it clear what the intent of the sender should be in order to commit the offence and this has only been clarified by the Divisional Court in England in the case of Chambers v DPP.[29] Essentially the sender must have intended that the message should be of an offensive or menacing character or alternatively, have recognised the risk that it may create fear or apprehension in any reasonable member of the public who reads or sees it.[30]

As the then Director of Public Prosecutions, Keir Starmer QC explained, in England it was necessary to put in place prosecutorial guidelines, which were designed, in view of difficulties in applying the legislation to social media, to help ensure a consistent approach to enforcement and balance the fundamental right of free speech with the need to prosecute serious wrongdoing:

The guidelines will help prosecutors to make fair and consistent decisions to prosecute in those cases that clearly require robust prosecution in accordance with the Code for Crown Prosecutors, and to uphold the right to freedom of speech in those cases where a communication might be considered grossly offensive, but the high threshold for prosecution is not met.[31]

It is warranted to suggest that prior to the introduction of these guidelines, the English legislation in this area was so broadly drafted as to lead to its use in too many cases (including the now infamous Chambers v DPP case, better known as the Twitter Joke Trial' mentioned above).

In view of these difficulties in England and Wales, it may be appropriate to make changes to existing legislation in Jersey to remove any uncertainty as to its application. Further, if new any new offence is enacted in response to this consultation, it must be prepared with an awareness of these difficulties, so as to avoid similar pitfalls.[32]

One of the difficulties in applying the existing offences to social media is that, arguably, it is important that the context in which a communication takes place is taken into account in deciding whether it should be characterised as criminal. The House of Lords Select Committee on Communications cites the following extract from the guidance, emphasising this point:

Prosecutors should have regard to the fact that the context in which interactive social media dialogue takes place is quite different to the context in which other communications take place. Access is ubiquitous and instantaneous. Banter, jokes and offensive comments are commonplace and often spontaneous. Communications intended for a few may reach millions.[33]

Revenge pornography

Notwithstanding that other offences may apply, the UK has recently amended legislation to make revenge pornography' a specific offence. The Criminal Justice and Courts Act 2015, which received Royal Ascent on 12 February 2015 states:

It is an offence for a person to disclose a private sexual photograph or film if the disclosure is made

- without the consent of an individual who appears in the photograph or film, and

- with the intention of causing that individual distress.[34]

Speaking on the topic of revenge pornography, Minister for Women and Equalities Nicky Morgan said:

Circulating intimate photos of an individual without their consent is

never acceptable. People are entitled to expect a reasonable level of respect and privacyit is right that those who do circulate these images are held to account, and that we educate young people to the hurt that can be caused by breaking this trust.[35]

never acceptable. People are entitled to expect a reasonable level of respect and privacyit is right that those who do circulate these images are held to account, and that we educate young people to the hurt that can be caused by breaking this trust.[35]

In Jersey, posting sexually explicit material onto the internet may constitute the sending of a message of a character prohibited by Article 51 of the TJL. In this context the focus will be on whether the sending of the particular message or communication is grossly offensive, indecent or obscene, not whether the image itself is grossly offensive, indecent or obscene. Posting revenge pornography online might also, potentially, form part of a course of conduct amounting to harassment. Further, where the material depicts a person under the age of 16, that may be an offence under Article 2 of the Protection of Children (Jersey) Law 1994.[36]

Existing legislation might therefore address incidents of revenge pornography. Nonetheless, given the harm that might be caused to a victim by just a single incident of revenge pornography, Jersey may wish to consider enacting a specific offence, perhaps of a similar nature to that enacted in the UK, to tackle this type of conduct and to ensure that the maximum penalty for such an offence is commensurate with the harm caused.

Therefore, whilst taking the opportunity to consult on the subject of inappropriate online behaviour, it was felt that this consultation should also seek input on whether it would be appropriate to consider making revenge pornography a specific new offence, or whether it would be preferable to use existing legislation where possible.

Education and awareness initiatives

Education and awareness-based approaches may also have a chance of effectively reducing harmful behaviour in the longer term. A number of jurisdictions undertake initiatives aimed to inform and educate internet users.

For example, Safer Internet Day is organised by the UK Safer Internet Centre in February of each year to promote the safe and responsible use of online

technology and mobile phones for children and young people.[37] The Anti-Bullying Week which takes place in November each year also tackles cyberbullying and has been taken up by other jurisdictions such as the Isle of Man.

technology and mobile phones for children and young people.[37] The Anti-Bullying Week which takes place in November each year also tackles cyberbullying and has been taken up by other jurisdictions such as the Isle of Man.

Australia's key anti-bullying event for schools, the National Day of Action Against Bullying, has been running since 2011. It provides resources to schools, children and parents regarding real world' bullying and cyberbullying.

In Malta the Be Smart Online project, which is partly funded by the European Union, endeavours to ensure that all stakeholders in the Island focus on the safer use of the internet by children and youths. The initiative is designed to raise awareness of the primary issues, as well as to promote and operate reporting facilities for internet abuse, and to support respective victims.

Summary

By studying international approaches to managing harmful electronic communications, we might better inform Jersey's own approach to grossly offensive, threatening and malicious behaviour online. The key points are as follows:

- Instantaneous communication that takes place on the internet and via social media has its own particular character, meaning that definitions of offences must be carefully crafted so that the imposition of an offence does not unnecessarily stifle free speech.

- Where the potential application of offences is unclear or offences are very broadly drafted, then guidelines for prosecutors and police can help to ensure that there is a consistent approach to legislation and help set parameters for where prosecution is appropriate.

- There are inherent difficulties in enforcing legislation on a medium such as the internet, which has no territorial boundaries.

- There are concerns regarding the effectiveness of legislation, particularly regarding the ability to police and prosecute in terms of resourcing and evidence.

- Legislation may be appropriate in some cases but other non-legislative approaches, including improved education and awareness, could also be considered to help address harmful behaviour in a constructive rather than a punitive way.

Section 4: Islanders' experiences and attitudes

Section 4: Islanders' experiences and attitudes

To inform policy development in this area, and to enhance its understanding of online behaviour and attitudes, the Government of Jersey commissioned Island Analysis to conduct quantitative research on usage and behaviour in relation to electronic communication in Jersey. This research had a particular focus on user experience and existing levels of concern around malicious, grossly offensive or threatening communications: including cyber-bullying.[38]

The research offered further insight regarding:

- online usage trends;

- online malpractice and level of concern;

- the need for additional education and support relating to online usage and security;

- different demands of various sections within the population regarding online usage; and

- the perceived need or otherwise for legislative amendments to enhance consumer protection online.

The full report is attached to this document as Annex 1, and key findings from this research are outlined below. In considering these findings it is important to note that this survey was conducted online and that respondents were therefore likely to be regular internet users.

Online usage

The research found that the laptop computer at home and the smart mobile phone were the two most used devices to access the internet. The tablet computer was also becoming more popular.

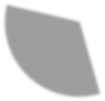

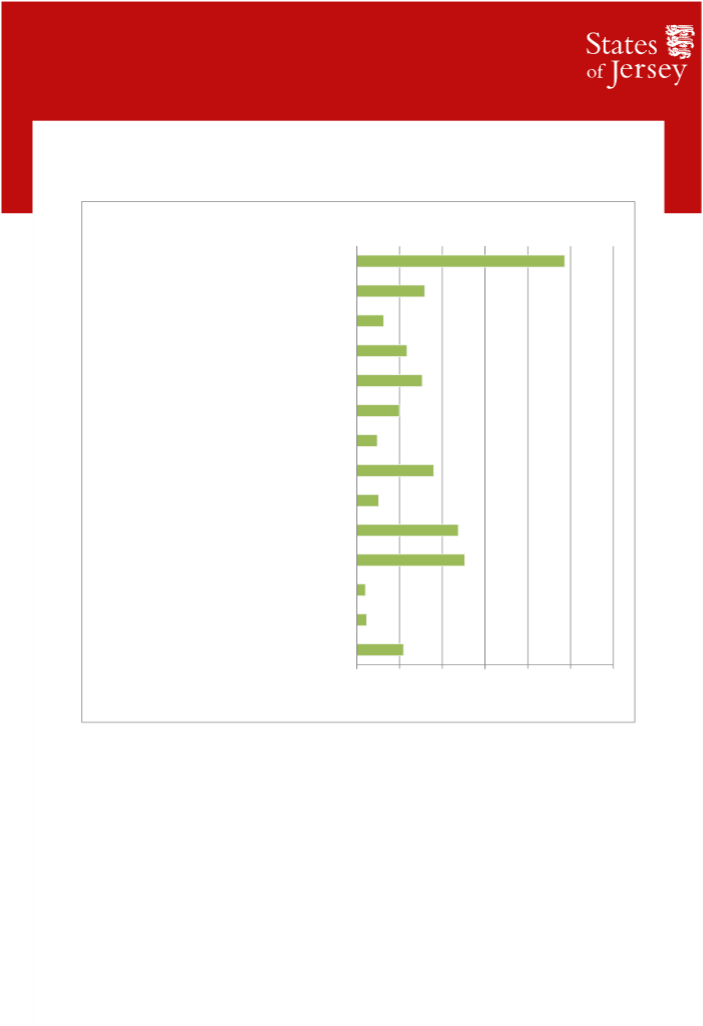

The most frequent online activities were browsing the internet, using social media sites and email. Half of respondents said they accessed social media sites several times a day and the most used social media sites were Facebook, Google+ and Twitter.

Figure 4: Online activities

Figure 4: Online activities

Frequency of undertaking following online activities

Browsing the internet

Browsing the internet

![]() Using social networking sites Several times per day Emailing Daily

Using social networking sites Several times per day Emailing Daily

Listening to radio and music

Weekly

Viewing videos or movies

Online gaming Occasionally (once a

month)

Adding or editing web

Rarely (once every few Telephone or video calls months)

Downloading music or Never

Online banking

Don't know or not Online shopping applicable

0% 50% 100%

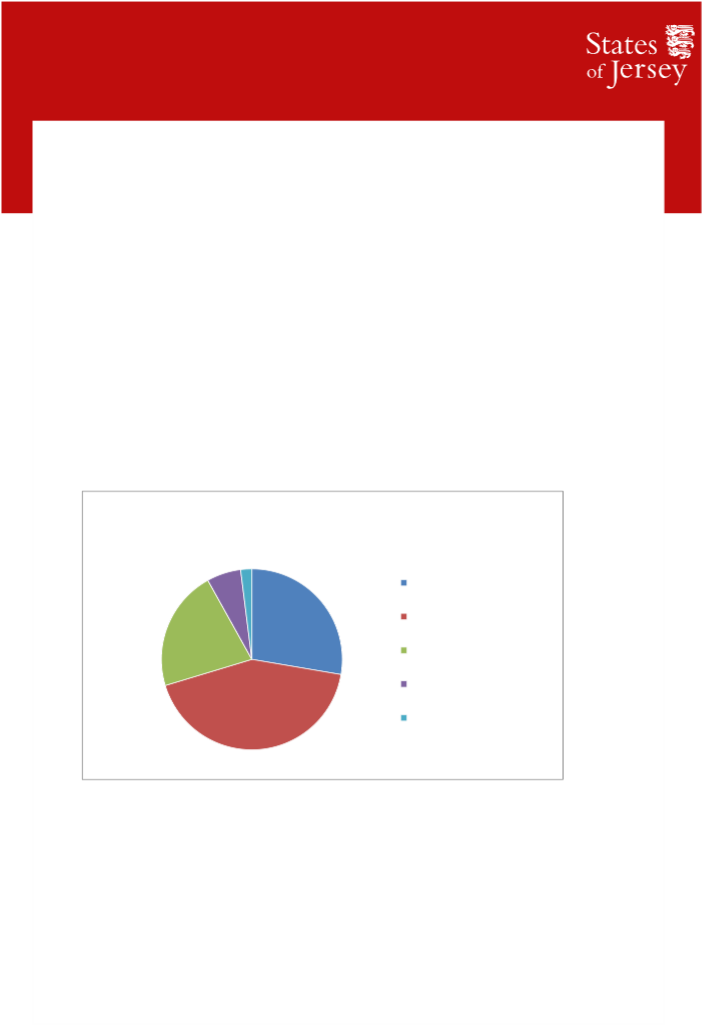

Level of concern about content online

Just under half of respondents indicated that they were either very concerned' (20%) or concerned' (26%) about being exposed to inappropriate, malicious or offensive content online. A further one in three was not particularly' concerned, with 20% saying they were not concerned at all'.

Figure 5: Level of concern

Level of concern for inappropriate, malicious or offensive content online

![]()

1%

1%

Very concerned

Very concerned

20% 20% Concerned

Not particularly concerned Not concerned at all

Not particularly concerned Not concerned at all

26%

33% No view

Confidence and awareness

Confidence and awareness

In Jersey, evidence suggests that majority of internet users are aware of how to respond to malicious, indecent or grossly offensive content, and feel confident in doing so.[39] The majority of respondents (72%) stated that they were very aware' or aware' of the actions that they could take with regard to blocking, getting help, or reporting offensive online content. A similar percentage (71%) indicated that they were very confident' or confident' of knowing what to do if they came across this type of content if they found it online. However, it is important to note that a significant proportion (27%) reported that they were not very confident' or not confident at all' of knowing what to do if they encountered this type of material and 28% said they were not very aware' or not aware at all' of actions that they could take.

Figure 6: Confidence

Confidence level of knowing what to do regarding malicious or offensive online content

2%

![]()

6% Very confident

6% Very confident

28% Fairly confident 21%

Not very confident Not confident at all No view

Not very confident Not confident at all No view

43%

Figure 7: Awareness

Figure 7: Awareness

Awareness of actions that could be taken with regard to blocking, getting help or reporting online content

![]()

Very aware

Very aware

4%

28% Aware

24%

Not very aware Not aware at all

Not very aware Not aware at all

44%

Users' experiences

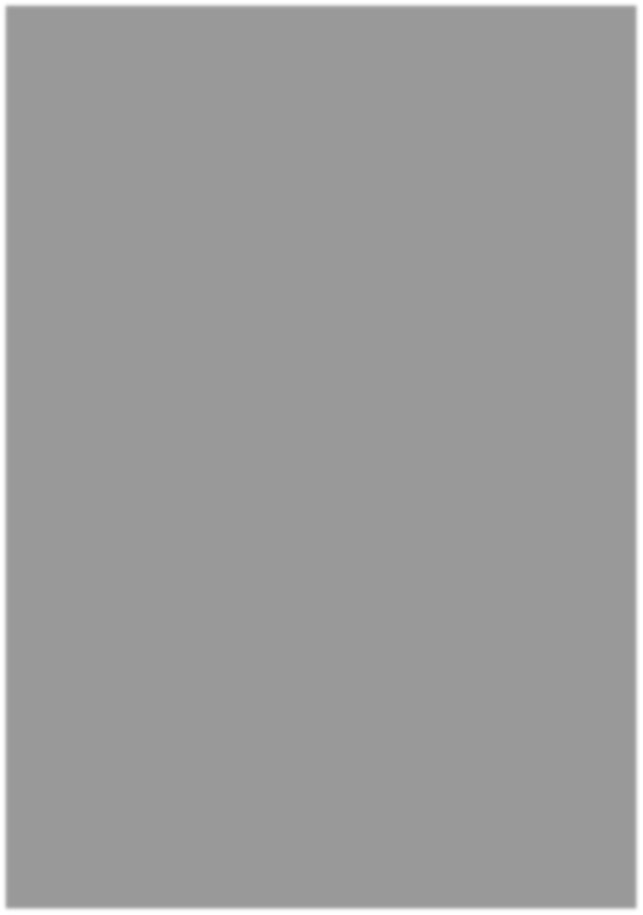

Respondents were asked to detail the issues that they had encountered online during the past 12 months. By far the most commonly reported problem was receiving unsolicited emails, followed by online fraud attempts and virus security threats. A small proportion (3%) of respondents said they had experienced online bullying while 2% said they had received threatening communications. Analysis of responses by age group indicates very little variation between age groups, however the 50 and over group reported a slight preponderance of online fraud attempts and unsolicited emails.

Figure 8: Experience of Online Issues

Figure 8: Experience of Online Issues

Experience of following online issues online in last 12 months

Unsolicited emails Unwanted sexual content Unwanted violent content Upsetting material Privacy issues

Unsolicited emails Unwanted sexual content Unwanted violent content Upsetting material Privacy issues

An offensive comment directed at you through social media

Threatening communications

Been offended by something that you have seen online

Experienced online bullying Security threat e.g. virus Online fraud attempt Identity theft

Financial loss None of the above

0 5 10 15 20 25 30

% of responses

Only half the respondents indicated that they had taken action against such online activity. Respondents were asked to state what action they had taken and many reported blocking the content or reporting it to the website.

The research indicates that such online experiences do not significantly affect the way that the majority use the internet, with 71% of respondents saying that it had no impact at all'. But when respondents were offered the opportunity to state how it had changed their behaviour, if at all, many reported being more cautious about which sites they use and being more vigilant regarding security.

Responsibility for internet safety

Responsibility for internet safety

Respondents were strongly of the view that, for adults, internet safety was the responsibility of individual users and, to a slightly lesser extent, website owners/creators. Respondents overwhelmingly felt that parents were responsible for the internet safety of children and, to a much lesser extent; the organisation that the minor was accessing the internet through (e.g. a school, workplace or college).

Summary

The findings from this research indicate that, as more people have access to the internet, social media use is becoming almost ubiquitous. A large proportion of internet users in Jersey feel confident going online and using social media, and say they know how to respond if they come across potentially harmful material. However, there is still a significant number of less confident users who might benefit from increased protection and/or improved education and information around internet safety.

It is clear that most of the respondents believe that adults bear the majority of responsibility for their own safety online. The situation is less clear-cut with minors, where the majority of respondents felt that parental responsibility was paramount but some felt that institutions such as schools have an important role to play

Only a small proportion of respondents reported experiencing online bullying or threatening communications. However, international cases demonstrate that, for the minority who do encounter malicious or threatening communications online, or who are victims of cyber bullying, the experience can be deeply troubling and in some cases have severe and potentially tragic consequences.

It should be clear in Jersey that a person may be guilty of an offence if he or she sends, or causes to be sent electronically, including by social media, a message that is of a grossly offensive, obscene or threatening character or sends a false electronic communication for the purpose of causing annoyance, inconvenience or needless anxiety to another.

While it does not appear that a new offence is needed to achieve this, it is also recognised that there have been difficulties in applying offences to behaviour of this nature in England and Wales. It might therefore be appropriate to take some action to avoid similar difficulties in Jersey by either clarifying the law or creating a new offence.

It is proposed that further consideration be given to whether it might be appropriate to introduce further definition and clarification into the TJL than is currently present in Article 51(a) or whether any further offences are required.

It is also proposed that any changes to legislation should draw on the principles established in the DPP's guidelines for when it would be appropriate to prosecute in respect of communications sent by social media.[40] Clarification of the law in line with the DPP's guidelines would have three primary objectives:

- to ensure that all types of threatening and bullying behaviour conducted via social media are potentially captured by the relevant offences;

- to provide greater certainty as to when offences will apply and to ensure that they only act as a restrictions on freedom of speech where it is necessary and proportionate to do so; and

- to provide, so far as is appropriate, that the context in which the communication is sent, including the age and maturity of the sender and the circumstances of the potential victim is taken into account in determining whether an offence has been committed.

Any amendments to the legislation in Jersey should be made in light of these objectives. This should help to avoid some of the difficulties faced in England and Wales, mentioned earlier in this paper, and mitigate concerns about threats to free speech.

One area where greater clarity may be useful is in relation to the intent that a person sending a communication must have if they are to commit an offence. One approach would be to provide expressly that a person only commits an offence where they intend that the message be threatening or grossly offensive or are reckless as to whether it would have that effect. So, where a message is intended purely as a joke and the person has no reason to think it would be perceived in another way, then they would not commit the offence. A variation on this approach would be for a person to commit an offence only where they intend that the message cause distress or anxiety to the particular recipient of the message.

One area where greater clarity may be useful is in relation to the intent that a person sending a communication must have if they are to commit an offence. One approach would be to provide expressly that a person only commits an offence where they intend that the message be threatening or grossly offensive or are reckless as to whether it would have that effect. So, where a message is intended purely as a joke and the person has no reason to think it would be perceived in another way, then they would not commit the offence. A variation on this approach would be for a person to commit an offence only where they intend that the message cause distress or anxiety to the particular recipient of the message.

Another area where greater clarity may be useful is in relation to the key terms used in the offence. For example, drawing on experience in England and Wales and the DPP's guidelines, it is proposed that a high threshold should be set when considering which communications should be considered grossly offensive, obscene or threatening. A merely offensive electronic communication, or one that is in bad taste, should not be contrary to criminal law. As mentioned previously, it is important that electronic communication is not held to a different standard than any other form of communication. Further, the expression of controversial views about serious or trivial matters and banter or humour, even if distasteful to some or painful to those subjected to it, should not be prohibited. It might be useful to consider defining key terms such as grossly offensive', to provide greater certainty in respect of such matters.

It is also worth considering whether some of the terms used in the TJL remain appropriate. For example it might be preferable to use the term threatening' rather than menacing' in setting the scope of the Article 51(a) TJL offence. This is on the basis that the two terms may have the same meaning, but threatening' is a more common term today and more readily understood.

General matters in relation to offences

In keeping with the objectives outlined above, there may be other ways in which the application of Article 51 of the TJL or any new offence can be tailored.

For example, it might be appropriate to provide for a defence in respect of these offences where the sender (or resender) of an electronic communication takes swift action to remove the communication or block access to it or to mitigate any harm that it may have caused (e.g. by apologising to the recipient(s)).

It may also be appropriate to provide for defences where the sender did not know and could not be expected to know, that the audience for the communication would include a particular alleged victim or would be as large as is ultimately the case.

It may also be appropriate to provide for defences where the sender did not know and could not be expected to know, that the audience for the communication would include a particular alleged victim or would be as large as is ultimately the case.

The legislative form that any amendments to Article 51 of the TJL, or any new offences should take will be the subject of further consideration in light of the outcomes of this consultation. If new offences are enacted then further consideration will also need to be given to amending the offence in Article 51 of the TJL to ensure the two laws work in harmony.

While we do not propose to amend the definition of telecommunications system in the TJL at this time, views are welcome on the application of this definition to electronic communications via social network sites such as Facebook and Twitter.

In order to ensure that the provisions are future proof', as far as it is practical to do so, it may also be appropriate to look to take powers for the States Assembly to be able to amend technical definitions such as this by Regulations.

As noted above, in England and Wales the DPP has drawn up guidelines to reduce the scope for inconsistent prosecution decisions to be taken regarding the very broad way in which the offences are framed in that jurisdiction. Whether it would be appropriate for Jersey's Law Officers, who are responsible for prosecutorial decision making, to draw up any similar guidelines in relation to any new offences would be a matter for them to consider in due course. It may be relevant to note in this regard that the application of a public interest test is always part of the process when deciding whether to pursue a prosecution.

Revenge Pornography

The posting of sexually explicit material onto the internet, without the consent of the individual depicted, may have devastating consequences for the victim of such an act. Given the potential harm involved, it is proposed that, notwithstanding the potential application of existing offences to this conduct, further investigation should be conducted into whether specific legislative provision should be made. This provision could be of a similar nature to that enacted in the UK and further views are sought on this proposal.

Section 6: Conclusion and questions for consultation

Section 6: Conclusion and questions for consultation

The Council of Ministers is seeking input on what the appropriate legislative position should be for dealing with grossly offensive, threatening, false or malicious electronic communications in Jersey.

The subject of electronic communications, including social media, is a complex and emotive one. It will be important therefore, that any approach takes into account the need to provide the relevant authorities with accessible, up-to-date legislation, whilst ensuring freedom of expression. It is also important that any changes to legislation are made in such a way that ensures they are future proof', as far as it is practical to do so.

This consultation proposes that, so far as it is necessary and appropriate, further clarity and certainty should be brought to the law in this area. The Council of Ministers is seeking input on whether existing legislation is appropriate and sufficient, or whether further offences, such as the specific act of revenge pornography', should be introduced.

Questions for consultation (Please give reasons for your response)

- Do you think that the approach proposed in this consultation document strikes the right balance between ensuring freedom of expression and the need to uphold the criminal law?

- Do you think that, as a matter of general principal, people should be held accountable for their activities conducted online in the same way that they are for activities conducted offline?

- Do you think it is appropriate to amend the existing offence in Article 51(a) of the Telecommunications (Jersey) Law 2002 so that it is clearer when the sending of a harmful online communication should be treated as criminal?

- Do you think that it would be appropriate to create a new offence so that is clearer when the sending of a harmful online communication should be treated as criminal?

- Do you think that alternative approaches to tackle this type of behaviour should be considered as well as/or instead of changes to legislation? If so, please give details.

Do you believe that a specific offence should be considered relating to revenge pornography'?

Do you believe that a specific offence should be considered relating to revenge pornography'? - Do you have any comments in relation to the topic that you feel have not been addressed in this consultation? If so, please give details.

Ways to respond

Telephone: +44 (0) 1534 448100

Email: HOCconsultation@gov.je

Write to: Harmful Electronic Communications Consultation

Cyril Le Marquand House

The Parade

St Helier

JE4 8UL

This consultation paper has been sent to the Public Consultation Register.