The official version of this document can be found via the PDF button.

The below content has been automatically generated from the original PDF and some formatting may have been lost, therefore it should not be relied upon to extract citations or propose amendments.

Health and Community Services Department

Administration Office 4th Floor

Peter Crill House Gloucester Street

St Helier

JE1 3QS

Deputy Mary Le Hegarat Chairman - Health and Social Security Scrutiny Panel Scrutiny Office

States Greffe

Morier House

JE1 1DD

9th October 2018

Dear Deputy Le Hegarat

I am writing in response to the review that you are undertaking in respect of mental health services in Jersey.

Based on the terms of reference of the review, my officers have written a detailed document responding to the questions posed by the panel. You have already received a copy of this.

As Minister for Health and Social Services I remain committed to improving mental health outcomes for Islanders. The Council of Ministers has made improving Islanders' wellbeing and mental and physical health one of its five strategic priorities for 2018-22.

Should you have any queries, please do not hesitate to contact me. Yours sincerely

Deputy Richard Renouf

Minister for Health and Social Services

![]() Health and Social Security Scrutiny Panel: 2018 Assessing Mental Health Services in Jersey.

Health and Social Security Scrutiny Panel: 2018 Assessing Mental Health Services in Jersey.

Health & Community Services Response

Introduction

The Hospital and Community Services department welcomes the opportunity to contribute to the Scrutiny of Mental Health Services in Jersey. This document contains the Departments response to the questions posed by the panel in relation to the Mental Health Strategy 2016-20:

- What are the current trends in mental health in Jersey?

- What progress has the States of Jersey made on implementing its mental health strategy and what further work is required?

- How have mental health services changed since the launch of the mental health strategy in 2015?

- What support is in place to ensure the organisations which provide mental health services are able to work in partnership in the best interests of the individual concerned?

- What are the potential risks and benefits of separating child and adult mental health services? How could any potential risks be mitigated?

- What examples of best practice are available from other jurisdictions that Jersey could learn from?

Since the publication of the strategy the operating context has changed significantly. Firstly, a new mental health law will be introduced on 1st October bringing the existing legislative framework up to modern and contemporary standards. Secondly, the States of Jersey has a new Chief Executive with a new vision and target operating model for public services and a clear focus on meeting the needs of the customer. Thirdly, a new Health Minister has been elected with a manifesto commitment to improve mental health and wellbeing. Finally, levels of expectation have grown within the Island community regarding their ability to access help and support from mental health services and a requirement for these services to be person-centred and available 24/7.

Background

The starting point for the most recent development of mental health services was 2012 when the States Assembly endorsed the strategic plan for Health & Social Services called A New Way Forward for Health and Social Care' (P82/2012). The plan outlined a programme of change to address the challenges facing the Island's Health and Social Care system and carried targeted investment for the Islands mental health services. As a result a number of service developments unfolded between 2013 and 2015 including for example Jersey Talking Therapies (JTT), and services for people abusing alcohol and/or engaging in substance misuse.

A specific review of mental health services then followed in 2015 involving all agencies connected to or providing mental health care and services as part of their work (education services, police services, voluntary sector and most importantly people who used services and their carers/families and friends). The review considered 4 main areas (below) and culminated in the first co-produced Mental Health Strategy (2016-2020) for Jersey

- public mental health and wellbeing (everyday stresses and strains)

- early intervention (nipping problems in the bud)

- acute intervention (when things get worse)

- recovery and support (helping people cope and return to their usual life)

The strategy addressed five key priorities reflecting a more holistic needs led approach to mental health and wellbeing with progress directed through a detailed work programme overseen by a Mental Health Implementation Group:

- Social Inclusion and Recovery

- Prevention and Early Intervention

- Service Access, Care Co-ordination and Continuity of Care

- Quality Improvement and Innovation

- Leadership and Accountability

Our response is informed by the work undertaken to date by members of this group.

.

Q1. What are the current trends in mental health in Jersey?

(a) Population Level

Mental Disorder

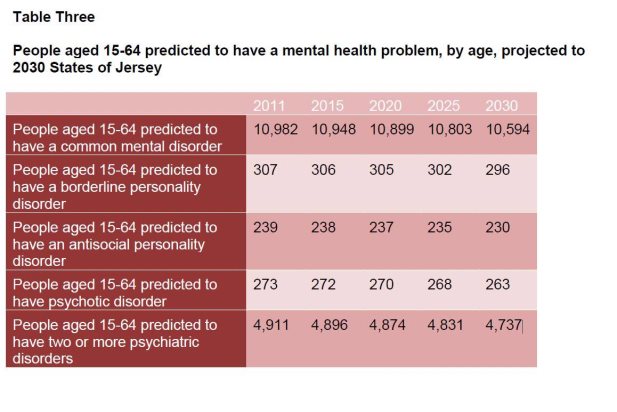

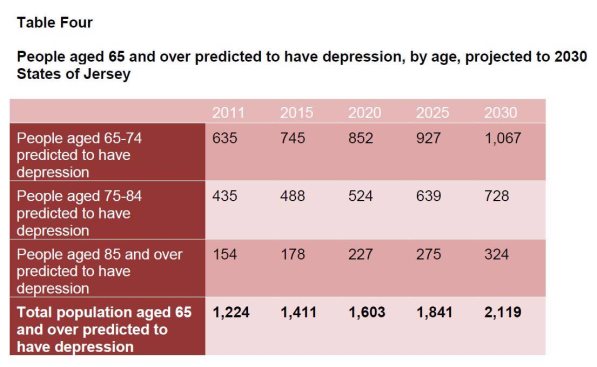

At the population level, the number of Islanders with a mental health disorder is predicted to decline gradually by 3.5% to 10,594 in 2030. The number of older adults who have depression is predicted to rise significantly from 1,224 people in 2011 to 2,119 in 2030, with the greatest increase amongst those aged 85 or older at 110%.

Predicted Mental Health Trends

Extract From: A Mental Health Strategy for Jersey (2016 - 2020)

Suicide

The current picture of suicide in Jersey shows that Jersey has comparable levels of suicide to the UK.

Table 5.6: Suicide ASR compared with England, London and the South West, 2012-2014, persons 10 years or over

| Number | ASR | 95% Confidence Interval (LL) | 95% Confidence Interval (UL) |

Jersey | 27 | 9.6 | 6.3 | 13.9 |

England | 14,122 | 10.0 | 9.8 | 10.2 |

London | 1,645 | 7.8 | 7.4 | 8.2 |

South West | 1,615 | 11.3 | 10.7 | 11.9 |

LL = confidence interval, lower limit; UL = confidence interval, upper limit Source: Jersey Public Health Statistics Unit, Public Health England

The table above shows rates that are comparable with other jurisdictions. The challenge in a small community such as ours is that our actual small numbers of deaths by suicide can fluctuate year to year and this therefore reduces the confidence in data that is seen in larger populations.

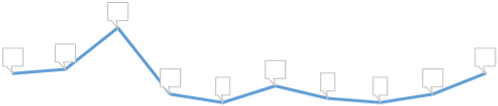

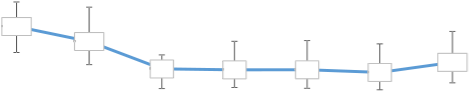

The actual numbers of suicide on an annual level can be seen below. Fluctuations year to year are evident with the highest number recorded in 2009. This period was identified elsewhere across the UK to have similarly higher rates. It is difficult to speculate as to causes of this increase although commenters often refer to the related economic climate has having an influence.

Deaths by suicide in Jersey

26

26

15 16 15

12

![]() 10 8 9 8 10

10 8 9 8 10

2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016

Because actual year on year numbers are subject to variation and can show fluctuations the annual rate is also prepared using an age standardised calculation with a three year rolling average. This allows the comparison with other jurisdictions as the data accounts for any differences in demographic differences across populations as well as allowing a clearer picture of any trends.

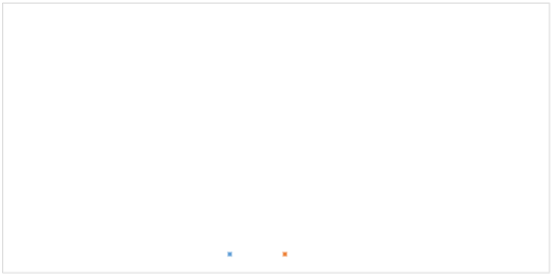

Age-standardised mortality rate by intentional self harm per 100,000 residents (3 year average)

25

20

20

17.8

15 14.8

10 9.4 9.2 9.2 8.7 10.7

5

0 ![]()

2008-2010 2009-2011 2010-2012 2011-2013 2012-2014 2013-2015 2014-2016

Data on deaths by suicide is typically around 2 years in arrears to allow for accurate recording of deaths allowing related inquests to conclude.

The Prevention of Suicide Framework reported specific gender trends around suicide locally with men aged between 40 – 49 most likely to complete suicide. This trend is reported elsewhere with suicides for men across the EU being four or five times higher than for women.

Prescribing

There has been a long and steady increase in antidepressant prescribing (mirrored in the UK) and a fairly steady use of anxiolytics (principally diazepam). Neither suggest an impact for Jersey Talking Therapies at this stage. The continued decline in hypnotic prescribing reflects improving practice among community prescribers.

Total number of prescription items dispensed in the community | |||

| Antidepressants (all types) | Anxiolytics | Hypnotics |

2011 | 76,333.00 | 15,292.00 | 27,383.00 |

2012 | 81,240.00 | 15,683.00 | 25,256.00 |

2013 | 87,427.00 | 16,367.00 | 25,042.00 |

2014 | 91,053.00 | 15,587.00 | 23,044.00 |

2015 | 94,931.00 | 15,055.00 | 19,486.00 |

2016 | 98,200.00 | 15,330.00 | 17,668.00 |

2017 | 101,452.00 | 14,749.00 | 16,377.00 |

2018* | 103,986.86 | 14,998.29 | 15,884.57 |

*2018 total estimated based on data for January - July

Operational Activity

Adult inpatient activity data suggests that the trends associated with bed occupancy, admissions and average length of stay compares favourably with the UK national average but with local fluctuating increases in activity. The overall position reflects low occupancy locally (77% of available beds) but an increase against the local 2015 position of 60.3%.

In comparison with UK organisations the percentage of admissions taking place under the mental health Law is below average but slightly raised against the local 2015 baseline position.

There is a sharp increase in the rate of emergency admissions from 7.2% in 2015 to 12.1% in 2017.

In older adult mental health services (for people aged 65 and over) the number of beds per 100,000 population is extremely high. The UK average has fallen which means compared to the UK Jersey is still providing more beds for its older adult population. This is counter intuitive to the model of providing care closer to home. As would be expected given the number of available beds admission rates remain high, although there is evidence of a downward trend in the number of admissions per 100,000 population locally since 2015.

Length of stay for this population has decreased by around 40% since 2015 and is now at 76 days. This is similar to the UK average.

Emergency readmission rates for this age group have increased since 2015 by 0.6% up to 4.3%

Since the implementation of the strategy caseload sizes of community mental health teams (CMHTS) have reduced significantly remaining above the average but well within the UK benchmark upper quartile range. Contact with CMHTS has risen since 2015 but remains below the UK average.

Data collected on activity relating to caseload of 16-25 year olds is not available to compare with the UK but over the last 2 years suggests a 2% increase locally.

Similarly contact activity with community teams for 16-25 year olds has risen by 2% on the 2016 position.

The number of CAMHS referrals received per 100,000 remains below the UK average 2403 (2017 benchmark figure) and just within the quartile range. The number of CAMHS referrals accepted and the number of re referrals shows a similar trend.

Waiting time for a CAMHS routine appointments is 3 weeks which is low compared to the UK average of 9 weeks and activity related to those who go on to have a second appointment showing a downward trend. There are no notable changes in "Did Not Attend" rates (DNA) which remain within the UK average.

Inpatient activity relating to CAMHS shows a downward trend for length of stay but a very large increase in admissions in 2018. It is difficult to provide trend analysis due to the small sample size of the data to make it statistically significant. It suggests changes in practice (one consultant retiring) and the vacancy of a CAMHS consultant are factors which have contributed to the current position.

Activity relating to workforce suggests the longer term trend with recruitment difficulties relating to psychiatrists and mental health nurses.

The trend in sickness rates across professional groups is down since 2015 from 9% in 2015 to 2%in 2017. Expenditure on bank and agency use is well below the UK average of 22% across professional groups at 13%.

- WhatprogresshastheStatesofJerseymadeonimplementingitsmentalhealthstrategyandwhatfurtherworkisrequired?

Since 2105 engagement and participative approaches such as the Citizens Panel and action learning sets have helped to deliver the priorities identified in the strategy. This has included work with other States of Jersey Departments, Community and Voluntary Sector organisations and local business an example of which includes developing an awareness raising programme to address issues of mental health and wellbeing in the workplace. Annual engagement events have been held over the last 3 years. These events were well attended by professionals from the States of Jersey, community voluntary sector services, carers and people with lived experience. The outcome of these events are as follows:

- Raise the profile of the strategy

- Ongoing engagement and continuing co-production

- Celebrating success by thanking people who have contributed

- Sharing experiences

- Identifying issues and solutions

- Agreeing priority areas of work

- Enable professionals to network

Key speakers have included:

- The right honourable Norman Lamb MP who spoke about the UK learning from the ongoing work to improve the mental health services.

- Anna Lewis who spoke about how recovery principles are being used to inform service improvement efforts and understand some of the tools and techniques being used to bring recovery approaches into all areas of practice.

The events include a 'market place' of 18 different organisations helping to raise awareness of existing services and networks including people from the Armed Forces Veterans' Mental Health, with guest speakers from Rock2Recovery.

New Legislation

The new Mental Health (Jersey) Law 2016 comes into force on the 1st October 2018. We have also produced a Code of Practice to support Implementation. From the 1st October 2018 we have made statutory provision for Independent mental Health Advocacy (IMHA) and Independent Capacity Advocacy (ICA) within the new Mental Health (Jersey) Law 2016 and Capacity and Self-Determination (Jersey) Law 2016.

The Mental Health Law training has been targeted and specialised. To date, training has been provided in respect of designated forms and statutory process; the changes and differences between the existing and new legislation; application and utilization of the Code of Practice.

Training has been provided to health and community services staff with attendance from all allied health staff across community mental health teams including older adult services and CAMHS. It has been provided to other government agencies e.g. probation service, police, primary care. Additionally training has been provided to third/independent sector agencies including MIND. This training does not take into account the ongoing provision of specialist advice which is provided by members of the Legislation Project Team to other professionals working both within and outside of Health and Community Services. Such advice and guidance is provided as requested.

Capacity and Self Determination (Jersey) Law 2016

As a result of the far-reaching nature of the new law, the breadth of training which has needed to be provided has been extensive. The majority of the training provided has been Foundation training. However, as need has dictated there has been the provision of some specialised training e.g. in relation to the undertaking of Capacity Assessments; the making of Best Interest Decisions. In addition to this, collaborative work

has been undertaken with the Adult Safeguarding Operational Team in devising and delivering training to employees in Health and Community Services which has explored the interface between Capacity and Adult Safeguarding.

To date over 3500 people have been trained which includes health professionals, legal professionals and members of the public. Separately, training has been devised and delivered to a smaller cohort of staff members who will be employed as Capacity and Liberty Assessors, fulfilling statutory functions under the new legislation.

Tier III: Specialised Tier II: Targeted Tier I: Foundation

Tier III: Specialised Tier II: Targeted Tier I: Foundation

Recovery College

The establishment of the Recovery College has been a huge success. It has now been open for a year and operated by people with lived experience of mental health issues with support from mental health professionals. It offers a range of educational courses on mental health conditions co-produced and delivered with experts by experience. In the three semesters of 2017, the college had enrolled 326 students. Student feedback included:

"Great course, lovely people and made to feel welcome. Completely different to what I thought - was much more about relaxation/meditation rather than purely physical - would definitely do the course again if it came up next time. Loved that it was a small class too."

"I really enjoyed the course - it was really empowering and instilled confidence and self- belief. Loved the balance of yoga and mindfulness meditation."

"I think this model of co-production is excellent and the recovery college is doing an excellent job at using education to improve recovery."

"[I] enjoyed hearing other peoples' experiences and thinking of the definitions of the word recovery."

Based on evidence from IMRoC (Implmenting Recovery through Organisational Change) and the other extensive work and advice from recovery experts in the UK we have been able to place the concept of recovery at the centre of all mental health related training and practice development across the life course in mental health services and embed this approach within our policy framework and related processes.

We have worked closely with the Public Health Department and the Community and Voluntary Sector to build a co-ordinated programme of mental wellbeing awareness delivered with the aim of reducing stigma and discrimination and continued to raise awareness of mental illness in the local media to address discrimination and stigmatisation of people who experience mental illness.

Jersey Wellfest

In January 2018 a small market place style event the Wellbeing Services Day' was open to professionals to find out about what services are available across the island to support wellbeing and mental health needs in Jersey, it enabled people to find out about different services and talk to the people who work within that service about what they can provide and how you can access the service. Learning from this event led to the development of the Jersey WellFest.

Jersey WellFest is an innovative way to ensure public engagement and partnership working. It is a free two-day annual event for Islanders of all ages, where they can try new sports and activities and learn about managing their own mental health and wellbeing.

The event coincides with World Mental Health Day in partnership with Children, Young People, Education and Skills and supported by other wellbeing partners including Mind Jersey, the Bosdet Foundation, Jersey Sport, Les Ormes and Creepy Valley, to promote mental, emotional and physical wellbeing.[1] The overall aim is to promote the importance and understanding of the interaction between mind, emotions and physical wellbeing and the things people can do to improve and look after themselves and to increase awareness of the many services and activities that are available on the Island to help reduce the stigma of mental health at the same time. The event includes talks, workshops, interactive market stalls and activities on staying mentally and physically fit.

Suicide Prevention Programme

The States of Jersey Prevention of Suicide Framework was released in November 2015 as part of the Mental Health Strategy. Good suicide

prevention first starts with good mental health. The Suicide Framework's aim is to reduce suicide in Jersey and has four key objectives:

Objective 1: Improve mental health and wellbeing in vulnerable groups Objective 2: Reduce stigma about suicidal feelings

Objective 3: Reduce the risk of suicide in high-risk individuals

Objective 4: Improve information and support to those bereaved or affected by suicide

The aim of the prevention of suicide framework to reduce suicide has challenged key stakeholders. It is recognised that with small numbers of suicide year to year with fluctuations it is difficult to measure success of commitments to reduce suicide. The challenge is that although deaths by suicide are relatively rare the factors and risks for suicide are relatively common. Risk factors include: self-harm; alcohol and substance misuse; unemployment; financial crisis; criminal behaviour; depression; relationship break-down and social isolation.

This situation has led to wider development of data measures that record some of these factors through the mental health scorecard. In this case data such as recording changes in self-harm and alcohol use can start to measure reductions in the risk to suicide.

Progress of the Prevention of Suicide Framework to date includes:

Ongoing Media opportunities to raise awareness include (i) an annual awareness around Suicide Prevention Day

Responding to relevant scrutiny, Safeguarding Partnership Board and Freedom of Information enquiries

Officers liaising with editorial teams proactively ahead of inquests including the provision of good practice media guidance in suicide reporting and re-actively to reporting which contravenes best practice

Provision of information on gov.je for families on mental health/suicide risk and service support accompanied by media coverage and targeted communications through schools.

Review of prevention of suicide training and implementation of Connecting With People, awareness, risk reduction and safety planning Training Programme

Developing baseline data on awareness and stigma of mental health

Inclusion of attitude based' questions in Jersey Opinions and Lifestyle Survey

Development of real time suicide audit process which monitors deaths suspected to be by suicide for any trends which could indicate related clusters and/or specific learning. The process also ensures the triggering of relevant support to family and friends. (Since commencement in 2018 the process has triggered one multi- agency meeting to review a small number of deaths suspected to be by suicide).

Production of Help is at Hand' a bereavement by suicide resource produced in partnership with people who have lived experience of bereavement by suicide.(xii) a review of lived experience of bereavement by suicide to inform planning which involved a 2.5 hour facilitated session followed by a summary report drawing on the experiences of bereavement by suicide and opinion on support and potential gaps and areas for improvement

A review of zero suicide methodology and the latest international evidence of zero suicide methodology to inform the provision of a position statement on considering the approach in the Jersey context.

- Provision of two key stakeholder forums

Training staff in Suicide Prevention has been delivered jointly with the public health department. The 'Connecting with People 'training programme has been running for 2 years and helps professionals to develop their understanding of suicidal behaviour, suicide mitigation and promotes their role in suicide prevention. It was introduced for those who work with adults and young people in emotional distress and crisis and is now being rolled out to key community and voluntary sector services who support people in need. Since the launch of the programme 241 people have been trained. More recently the training programme has been extended through Jersey Recovery College by supporting 7 more people to become trainers. This involves Mind Jersey, Jersey Employment Trust and peer trainers from the Jersey Recovery College. With events planned for delivering training in the autumn.

Children and Young People: Enhancing early intervention in mental health and wellbeing in schools: In place

Improving mental health and wellbeing in vulnerable groups has been delivered with a focus on young people in schools and also covered in the response provided by the Children's Education and Young Peoples department. As a result of the Mental Health Strategy two Primary Mental Health Worker's, were seconded from CAMHS to education. Since June 2017 they have provided in-reach into schools. They offer support to colleagues in education to support young people experiencing mild mental health issues and bring education and health closer to delivering evidence-based interventions for children, young people and families at the very earliest opportunity.

Citizens Panel

A citizen panel made up of a different people from across the island, chosen at random, worked together to identify key features that should be considered when planning improvements to mental health services. The panel had a chance to hear from experts, including professionals and people who use services, including the opportunity to ask questions. The recommendations from the citizen panel were used to decide the priorities identified in the Mental Health Strategy and provided an important link between clinicians and professionals working in the services and the local community. The panel have been involved in all the programmes of work to date including the Codes of Practice for the new mental health legislation and the Estates Feasibility study.

Mental Health Network

Workshops were held in December 2016 and March 2017 for both professionals and people with lived experience to fully explore the challenges and benefits of adopting a coproduction approach to working. The outcome was to recommend the establishment of a Mental Health Network.

In 2018 the Jersey Recovery College as a key partner led on defining the scope of the Mental Health Network, however due to long term sickness the development could not progress at that time but this had provided an opportunity to link to the wider States customer focus work as part of the One Government strategy

Jersey Online Directory

An enhancement of the Jersey Online Directory has been completed, to ensure more information was included on mental health issues and was made available to the public. Jersey Online Directory includes information about all services offered for support on the island for mental health issues.[2]

Prevention and Early Intervention:

To date the work targeted around early intervention and prevention has focused on developing relationships with primary care, education and schools to promote health and wellbeing and creating ability to respond quickly when people start to have mental health problems.

Jersey Talking Therapies

As part of the P82 funding, JTT was given a clear focus to develop further to ensure improvements in waiting times and access were achieved and align the model with the Increasing Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) model developed in the UK

Three half-day workshops were held on 25th and 26th September 2017 and were attended by approximately 40 people. To progress this work. A summary of this report is available on request.

Older Adult Mental health

In older adult services care closer to home has been promoted and facilitated by building closer links with primary care practices through the development of a primary care mental health team (PCMHT) and Hospital Liaison Service which supports older people with acute and/or complex functional mental health needs and dementia.

The rapid response multidisciplinary reablement team was set up to provide care closer to home and is accessible during extended hours. The team was expanded, incorporating new services for home care reablement which includes 2 Mental Health Nurses supporting people to avoid hospital admission (or be discharged earlier) and to be supported to remain independent in their own homes.

The Memory Assessment Service was developed as a multidisciplinary team which includes medical, social work, occupational therapy, nursing and psychology input to provide a holistic rather than a medical based approach. The enhancement of the team has enabled the development of services for younger people who experience dementia for whom the progression of dementia, life factors and needs, require a different assessment and support pathway. The enhanced service has also enabled development of initial post diagnostic support, and an individualised support plan to people who have received a diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or dementia. The service improves the ability of care professionals (including GPs) to identify signs of cognitive impairment so that they are confident about making referrals.

The Memory Assessment Service has achieved accreditation through the Memory Services National Accreditation Programme (MSNAP), which involved meeting a number of key standards in relation to the provision of the service, of which feedback from people who use the service was an integral part.

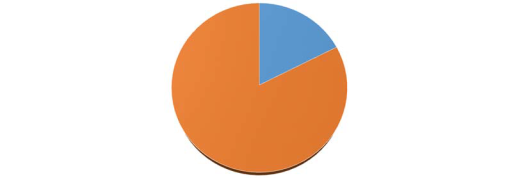

MAS CASELOAD - SEPTEMBER 2018

MAS CASELOAD - SEPTEMBER 2018

18%

18%

82%

< 65yrs > 65 yrs

Enhanced Mental Health Liaison for older people

The older adult mental health hospital liaison service was introduced to the Jersey General Hospital as a result of P82 funding. Whilst the service is currently for older people with mental health needs, there is a plan to expand into a hospital based liaison service for all adults. The service currently consists of a full time Clinical Nurse Specialist and Nurse Practitioner and Consultant Psychiatrist medical time, and provides an 8am to 8pm service.

Initial data suggests that the number of delayed transfers for older people with a mental health need has reduced since the introduction of the service, enabling better outcomes for individuals, and more effective use of acute beds.

Criminal Justice and Mental Health

Mental health training has been delivered to staff in prison, probation and police. The training includes 6 sessions on various topics of mental health awareness, so that staff across the system can understand more about mental health issues.

Detainees assessed by the Forensic Medical Examiner in police custody are assessed in a timely manner and where clinically indicated they are connected into health and social care services.

HMP La Moye has a functional urgent and routine pathway in which individuals are assessed by a mental health professional and care/treatment plans formulated.

The Mental Health Quality Standards and Reporting Framework

Developed specifically for Jersey. The process included a literature review of similar frameworks from across the world and a series of workshops with key stakeholders including carers and people with lived experience to identify themes and approaches that are relevant for Jersey. The five priority areas come directly from the Mental Health Strategy which itself was developed with input from key stakeholders.

An Annual Mental Health Quality Report (2016) was published at the Engagement Day in 2017, it reports on a number of activities on how the services are performing against the priority areas of the Mental Health Strategy. The annual report for 2016 is available online at www.gov.je.

Jersey has joined the NHS Benchmarking network and submitted data to the Inpatient, and Community Mental Health and also the CAMHS exercises for three years. Data is collated and sent to the network to compare Jersey with other jurisdictions and an annual report is published. The results are shared with service leads and used in planning service developments as well as providing assurance and sharing best practice/learning from others.

Further work required..

The following areas of work will be incorporated into the Mental Health Improvement Plan which will also include a refresh of the strategy

24/7 services

There remains a recognised need however to develop core 24 outreach services into community combining community triage service

Embedding new laws

As with any new law the first phase of implementation may encounter some problems for people as they start to work with a new legal framework. Work will continue to support training and supervision and monitoring of compliance against the legislation to ensure the States fulfils its legal obligations particularly with regard to upholding rights and responsibilities.

Dementia

Completing the work on the Dementia Strategy – the scale of Dementia related illness will follow the demographic trend for Jersey over the next 10 years and will require a refresh of the needs assessment.

Criminal Justice Mental Health

Work is ongoing with partners across the States of Jersey to plan for improved mental health services within health and social care and across the criminal justice system including development of a place of safety' and strengthening the interface with probation services. A 6 month Community Triage Pilot took place during October 2017 to April 2018. The service provided an out of hour's integrated response involving health and social care, the Police and Ambulance services to those experiencing a mental health crisis. During the pilot 29 individuals were referred into mental health services 10 were seen in their own homes. The outcome of this pilot improved the service user experience and outcome, avoided unnecessary Mental Health Law Detentions under Article 47, reduced repeat attendances at the Emergency Department and built resilience, improved collaboration between the emergency Services. The learning from this will now be taken forward under the Mental Health Improvement Plan which will set out the next phase of development and improvement relating to mental health services. The data suggests that more people are coming into contact with the police because of welfare' related incidents.

Police Data

Police Data

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

261 33

261 33 ![]()

![]()

![]() 232

232

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() 52

52![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() 256

256

![]()

![]()

65

65

1476 1239

1057

2015 2016 2017

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Police welfare incidents

Police welfare incidents ![]() Art. 47 custody detentions

Art. 47 custody detentions ![]() Full arrest for mental health need

Full arrest for mental health need

Jersey Talking Therapies

Work will continue to develop the next level of service with a focus on development of a trauma informed' pathway in response to recommendation 8.4 of the Children's Inquiry.

Workforce Strategy

The Mental Health Workforce Strategy is incorporated within the States of Jersey HSSD Strategic Workforce Plan, July 2017 and the C&SS Workforce Plan July 2017 (which includes mental health services). This will needs refreshing and updating to reflect current context for mental health services under the new Target Operating Model

Asset Management Plan for Mental Health estate

A Strategic Outline Case has been completed following a feasibility study for new mental health services to provide modern fit for purpose facilities, in line with UK NHS guidance. The Strategic Outline Business Case described the case for change, recognising the defined and clear direction documented in P.82/2012. This is currently being reviewed to ensure the business case is fit for purpose in the current context. Plans for improving the quality of estate in the meantime focus on the actions required in response to the recent Health and Safety inspection of Orchard House

Annual Mental Health Quality Report

Will continue to be developed to move to more outcomes based reporting.

- How have mental health services changed since the launch of the mental health strategy in 2015?

Since the launch of the mental health strategy in 2015 the following changes have been noted in services:

- Visibility & Integration: The mental health services are now much more visible in the community challenging the barrier and stigma associated with mental health. The integration between Child & Adolescent Mental Health Services and the Primary Mental Health Team as well as Jersey Talking Therapies and the Alcohol Pathway Team has shown improved pathways developed for service users.

- Social Inclusion: There is improved social inclusion as the States of Jersey is working more in partnership with the community and voluntary sector via formal (contracts) and informal arrangements. Through yearly public engagements services are able to review where things are going well and get direct feedback from the public on how our services are performing.

- Better relationships: the community and voluntary sector are treated as equal partners in the delivery of mental health services. Charities such as Recovery College, MIND Jersey, JET, Jersey Alzheimer's and others are regularly contributing as equal partners to the islands populations alongside our statutory services.

- Recovery focused care: there is increased capacity to support people in the community more rather than a hospital settings using a recovery focused model. The Alcohol Pathway Team has increased the number of people offered community detoxes, reducing demand for hospital beds and offering clients alternative/appropriate support in their own environments.

- Improved coordination with Primary Care: the introduction of the older adult's primary mental health team and developing a cluster service to support GP surgeries has improved coordination. The Rapid Response Team support both GP and Care homes supporting them to manage client's with mental health issues appropriate support in the least restrictive environment.

- Improved Early Diagnoses: we have seen improved early diagnoses of people with dementia through consistency of GP surgeries working closely with the Memory Assessment Clinic. Early diagnosis and intervention in improving quality of life and delaying unnecessary admissions into hospitals and care homes.

- Supporting the most vulnerable: there has also been provisions made for our most vulnerable clients who may not have family and appropriate others to speak on their behalf when they are being treated under the Jersey mental health law. Independent Mental Health advocacy supports them to understand their rights, treatment and have a voice in their care.

- Holistic Approach: the holistic approach to supporting people who need support with their mental health accessing other services that contribute to their recovery. Having mental health professionals also working in social security supporting areas such as return to work schemes has improved relations with employers to understand and support their staff who may have a mental health problems return to work in a supported way.

- Parity of esteem: We are in the early phases of improving the parity of esteem between physical and mental health issues across all our services but the message is getting through and getting recognized.

- What support is in place to ensure the organisations which provide mental health services are able to work in partnership in the best interests of the individual concerned?

Services across States of Jersey has signed up to the new Target Operating Model to ensure the delivery of those objectives. The model across all services has a number of objectives and priorities under the one government plan that aim to ensure the following:

- Co-production with individuals and families

- Individuals are supported to live safely in their homes, with families and communities

- Response is appropriate, proportionate and timely

- Developing one, single point of referral

- Reducing hand-offs through Integrated Care Pathways

- Support is provided to minimise/prevent an escalation of need

- Support and intervention takes place within legislative and policy frameworks based on an assessment of need

- Support and intervention is outcome focused

There are various service level agreements that Health and Community Services provide grants to within community and voluntary sectors services, to work in partnership and support care and people with lived experience. All community and voluntary sector services level agreements are subject to two meetings a year where progress and key performance indicator are reviewed and support for the service is offered.

- What are the potential risks and benefits of separating child and adult mental health services? How could any potential risks be mitigated?

Currently Children's mental health services (Specialist CAMHS) are located in Health & Community Services and follows the specialist health services models recognised by the UK and international community. Specialist CAMHS, which is often referred to as secondary/tertiary health services, provides care and treatment interventions (sometimes under legal detention) for those children and young people with the more severe, diagnosable mental disorders often presenting with co-morbidity e.g. mental illness/epilepsy, mental illness/eating disorder, mental illness/substance misuse etc. and hence sits within health services, staffed by mainly health professionals and functions within a clinical governance system. The children's emotional and wellbeing services are located within Education and other children's services through the P82 investment programme. Close links are maintained between all the services.

Key potential benefits and risks identified separating child and adult mental health services include:

Benefits:

- Improves opportunity for making sure the child or young person is at the centre of care

- Improves wrap around care' and transitions for children and young people

- Improve collaborative/partnership working across specialist CAMHS, Children's services and Education

- Improves the understanding of and quality of referrals for mild, moderate and severe mental health needs for children and young people

- Provides and opportunity to develop a more system based model across education, social care and health services.

- Opportunity for a new management structure that is child and young person focussed

- Opportunity for resources investment

- Opportunity for joint learning

Risks:

- Potential lack of patient advocacy – mitigated by strong and resourced independent advocacy service for children and young people

- Sitting a large education focussed structure – mitigated by involvement of existing health roles working in education (i.e. mental health workers)

- Change in clinical/health management structure may result in a lack of governance and supported adherence for professional bodies and codes of conduct – mitigated by a professional supervision and governance framework aligned to education and health

- Medical Officer and chief Nurse sitting outside of management and operational structure – mitigated through reporting requirements and oversight arrangements for professional practice as part of the governance framework.

- Does not enable a whole family system model – mitigated by developing the Think Family' model of care and support

- Requires working to two Ministers – mitigated by clear briefing to both Ministers

- No medical framework does not allows for emergency medical cover in a crisis/emergency to sustain delivery of service – mitigated through a service level agreement that addresses the clinical and professional governance issues professional/medical staff arrangements as part of an on call rota.

- Restricts shared prescribing practices - mitigated by prescribing protocols and standards

- Potential lack in continuation of wrap around care when transitioning into adult world of services – mitigated by the development of a transitional care pathway

- Restricts ability to ensure parity of health and mental health care – mitigated by the assessment and review process related to care planning and formulation and regular clinical review

- Out of hours system will sit in a different management and operational structure – mitigated as above in relation to governance framework

5. What examples of best practice are available from other jurisdictions that Jersey could learn from?

Global

The World Health Organisation identifies four key global objectives for mental health; more effective leadership and governance for mental health, the provision of comprehensive, integrated and responsive mental health and social care services in community based settings, implementation of strategies for promotion and prevention in mental health and strengthened information systems, evidence and research for mental health. [3]

In Ireland, best practice guidance sets out key principles that should be applied in any mental health setting including; (1) recovery-oriented care and support, (2) effective care and support, (3) selfcare and support, (4) leadership, governance and management, and (5) workforce. All mental health services across Ireland are assessed against the best practice guidance in order to identify good practice and areas of where improvements can be made. The best practice guidance includes a train the trainer' programme to support the introduction of the guidance. The trainers known as "Quality Champions" train and mentor self-assessment teams in each service.[4]

Australia

Australia is leading the way in the development of perinatal services. Australian practitioners have developed different ways to engage fathers during the perinatal period that does not rely on their presence at clinics. It includes high quality on line resources, groups aimed at fathers and the innovative use of digital technology to connect with fathers across the perinatal period. The project SMS4dads" involves sending regular text messages to fathers across the perinatal period including tips, information, advice and links to services. Messages are linked to the developmental stage of the baby, the fathers own well-being, his relationship with his partner and his relationship with the baby. Fathers are sent a mood tracker every 3 weeks. [5]

United Kingdom

The traditional age split between Child and Adolescent Mental Health services (CAMHS) and Adult Mental Health services (AMHS) has resulted in services in the UK being described as weakest at the point of highest need'. Across the jurisdictions of the UK there are efforts to address the problem by improving the process of transition and transfer of care. In England and Wales there is support for new models of care for young people that bridge the traditional age gap between CAMHS and AMHS such as 16 to 25 year old services. National Institution for Clinical Effectiveness (NICE 2016) recommends that good transition planning for young people include the designation of a named worker that the young person trusts, who will act as a link between child and adult services and provide continuity of support for a minimum of six months before and after transfer. NICE (2016) also recommends that attention is paid to supporting the infrastructure ensuring there is a senior executive accountable for transition strategies and an operational level champion supporting the process.

Key good practice points have been identified as improving the experience of transition from child to adult services. These include; (1) developmental and family-oriented approach, (2) emphasis on meaningful engagement (3)

joint working and close liaison with other agencies – statutory and non- statutory, (4) range of psychological, psychiatric and psychosocial interventions (5) mix of expertise from CAMHS and AMHS (6) availability of appropriate crisis, intensive community treatment and in-patient care (7) an emphasis on supporting young people in getting on with their lives and (8) involvement of young people in service development. To combat gaps in service and inequity of provision, an increasing number of mental health services have developed a designated clinical liaison or designated link posts to facilitate joint working between CAMHS and AMHS. Examples of new models of care include the setting up of transition clinics (Nottingham) primary care youth clinics with an embedded mental health specialist or robust links to specialist teams (London – The Well Centre for 13 to 20 year olds).[6]

Nuremberg and Europe

In 2001 Nuremberg Action Against Depression was initiated as a community-based model that implemented a specific four level approach to reduce suicidal behaviours. Based on the positive results of the project and significantly reducing suicidal acts and behaviour, 18 international partners representing 16 different European countries the European Action Against Depression.

The four level approach has a specific goal of improving care for patients suffering from depression and preventing suicidal behaviour and comprises of; (1) primary care and mental health care GP's and paediatricians invited to educational workshops about how to recognise and treat depression and explore suicidal tendency in the primary care setting, (2) general public large scale depression awareness campaigns to improve knowledge about adequate treatments of depression in general and to reduce the stigmatisation of the topic depression' and the affected individuals, (3) patients, high-risk groups and relatives being provided emergency cards' guaranteeing direct access to professional help in a suicidal crisis and (4) community facilitators and stakeholders providing educational workshops to various target groups playing an important role in disseminating knowledge about depressive disorders such as Police, Priests, and the media who have a role in preventing copycat suicides.[7]

United States of America

America is focusing on suicide prevention having recognised that one programme to prevent suicide in a community is considered not enough. The examples of community-based programmes that effectively reduced suicidal behaviours all involved numerous strategies working together. A comprehensive approach to suicide prevention and mental health promotion is delivered through nine strategies that can be delivered through a number of activities such as programmes, policies, practices and services. Suicide prevention programmes are identified to more likely succeed if they involve five guiding principles; (1) engaging with people with lived experience, (2) partnerships and collaboration, (3) safe and effective messaging and reporting, (4) culturally competent approaches and (5) evidence-based prevention.[8]

United States of America, New Mexico and National

Identified as a programme with evidence of effectiveness, MASPP is a public health-oriented suicide prevention and intervention programme originally developed for a small American Indian tribe in rural New Mexico to target high rates of suicide among its adolescents and young adults. The goals of the programme are to reduce the incidence of adolescent suicides and suicide attempts through community education about suicide and related behavioural issues, such as child abuse and neglect, family violence, trauma and alcohol and substance abuse. Central features of the programme include formalised surveillance of suicide-related behaviours, a school- based suicide prevention curriculum, community education, enhanced screening and clinical services and extensive outreach provided through schools, health clinics, social services programmes and neighbourhood volunteers recruited to serve as helpers' and can offer low levels support and assistance into professionals services in a less formal setting.[9]

Canada

Canada are developing some exciting initiatives linked to mental health in the workplace. The project maintains that the workplace can contribute to the development of mental health problems and illness such as depression and anxiety and the objective is to create mentally healthy workplaces. A National standard has been implemented to provide organisations across Canada with the tools to achieve measurable improvement in psychological health and safety for Canadian employees.[10]

Integrated Stepped Care Pathways

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2011) describe a stepped care' model of integrated services and care pathways that support a service user's journey through a range of often increasingly specialised services. It brings together Primary Mental Health and CMHTs with specialist services, and is flexible depending on the client's needs:

Step 1 - supported self-management of psychological and emotional wellbeing, social prescribing, peer experts and mentors, health trainers, psychological wellbeing practitioners trained in cognitive behavioural treatments for people with mild to moderate anxiety and depression, and access to e-mental health services such as on-line peer support groups.

Step 2 - coordinated care involving the primary care team, including provision of low intensity therapies and links to employment support, carer support and other social support services. Many service users will be supported well by an individual clinician – most commonly a GP, but it could be a practice nurse, a health visitor, a psychological wellbeing practitioner or a counsellor.

Step 3 - high intensity psychological therapies and/or medication for people with more complex needs (moderate to severe depression or anxiety disorders, psychosis, and co-morbid physical health problems). Initial treatment should be psychological therapy delivered by a high intensity worker, and/or medication. For people with moderate to severe depression whose symptoms do not respond to these interventions, NICE recommends a multiprofessional collaborative care approach.

Step 4 - specialist mental health care, including extended and intensive therapies, with pathways between the primary care, Psychological Therapies and specialist mental health services. Specialist mental health teams may operate across several practices, with a practice-affiliated specialist team member (for instance a community psychiatric nurse). This model enables specialist mental health to be provided in a primary care setting to avoid the need for cumbersome referral processes and the stigmatisation that sometimes affects service users in secondary care settings.

Recovery Based Models of Care

People using mental health services have long requested more information, support for self-directed care and self-management, empowerment and choice and employment of peers in providing services[11]. This has driven the development of recovery-oriented practice in mental health services over the past 20 years.

Recovery orientation requires a focus on approaches which foster hope and the possibility of reaching personal goals and ambitions; taking back control of symptoms and life; developing valued roles and relationships; finding meaning and purpose, and having the opportunity to do what is personally valued to build a life beyond illness.

Cultural change in mental health services towards recovery-oriented practice is supported by mental health policy. No Health without Mental Health sets the objective that more people with mental health problems will recover' by having 'a good quality of life – greater ability to manage their own lives, stronger social relationships, a greater sense of purpose, the skills they need for living and working, improved chances in education, better employment rates and a suitable and stable place to live.'12131415. Recovery practice is also recommended, with top priorities for mental health services including supporting self-management, educating people about their conditions and expanding the peer workforce (workers with expertise by personal experience of mental health challenges).

At the heart of the concept of recovery is a set of values about a person without the continuing presence of mental health symptoms. Recovery emphasises the importance of hope in sustaining motivation and supporting expectations of an individually fulfilled life. In Making Recovery a Reality[12] the authors argue that argue that recovery does not necessarily mean cure. Instead it focuses on "the unique journey of an individual living with mental health problems to build a life for themselves beyond illness (social recovery'). Thus, a person can recover their life, without necessarily recovering from' their illness."

Recovery orientated mental health service models[13] are designed to move specialist mental health care from traditional treatment and cure' models offering open-ended support (sometimes amounting to community based institutionalisation) to realistically optimistic, recovery-based services with time-limited, focused and evidence based interventions that reduce distress and enhance self-determination, social inclusion and quality of life.

Primary Care Mental Health Services

The UK Joint Commissioning Panel for Mental Health estimates that, in a group of 2000 patients at any one time, an average general practice will be treating:

• 352 people with a common mental health problem

• 8 with psychosis

• 120 with alcohol dependency

• 60 with drug dependency

• 352 with a sub-threshold common mental health problem

• 120 with a sub-threshold psychosis

• 176 with a personality disorder

• 125 (out of the 500 on an average GP practice list) with a long-term condition with a co-morbid mental illness

• 100 with medically unexplained symptoms not attributable to any other psychiatric problem (MUS).

The Joint Commissioning Panel for Mental Health estimate that this means about one in four of a full time GP's patients will need treatment for mental health problems in Primary Care. For common mental disorder which is the most prevalent mental disorder only 24% receive any intervention.

Strong and effective Primary Care is typically considered to be critical to a high performing health care system because of its role in improving outcomes and containing costs[14],[15].

Community Mental Health Teams (CMHTs)

A recent Cochrane Review (2007) of the value of CMHTs for people with severe mental illness and personality disorders concluded that they promoted greater acceptance of treatment (than non-team standard care), and may also be superior in reducing hospital admission and avoiding death by suicide[16]

The Mental Health Review noted that CMHTs need to be part of a specialist mental health service that includes acute care (crisis and home treatment, inservice users), rehabilitation, and highly specialist teams working with specific conditions, as well as a range of statutory and non-statutory services that support the delivery of care.

The overlap between mental and physical health

There is growing evidence that supporting the psychological and mental health needs of people with long-term conditions more effectively can lead to improvements in both mental and physical health. For example, addressing the psychological needs of people with diabetes can improve clinical outcomes, quality of life, relationships with health care professionals and carers, dietary control and overall prognosis[17].

Existing health care provision often fails to realise these opportunities. A separation of mental and physical health is hard-wired into institutional arrangements, payment systems and professional training curricula. As a result, co-morbid mental health problems commonly go undetected among people with long-term conditions, and where problems are detected the support provided is often not effectively linked or co-ordinated with care provided for physical problems.

Improving support for the mental health and psychological aspects of physical illness cannot mean treating a large number of additional people within specialist mental health services; an expansion along these lines would be both unaffordable and undesirable. What is needed is a Primary Care-based approach.

Primary Care is a key area where steps to promote the mental wellbeing of individuals with long-term conditions can be initiated. It is also the main source of formal support for those individuals identified as having mental health problems – only 10 per cent receive a referral to specialist mental health services.

A number of approaches could be taken towards integrating mental health and Primary Care.

Collaborative care is recommended by National Institute Clinical Excellence for supporting people with long-term conditions and co-morbid depression in Primary Care[18]. Key elements of the collaborative care model include:

- a case manager responsible for co-ordination of different components of care

- a structured care management plan, shared with the patient

- systematic follow-up

- a multi-professional approach with mechanisms to enable closer working between primary care and specialists

- patient education and support for self-management

- a stepped care approach limiting more intensive interventions to those who do not respond to initial care.

Research suggests approaches based on this model can improve outcomes without additional costs and can potentially deliver net savings[19]. For example:

- collaborative care for people with diabetes and co-morbid depression improved depression outcomes in USA-based studies and led to slight reductions in total medical costs over a two-year period, with cost increases in year one being outweighed by returns in year two.2425 A longer-term study found a 14 per cent reduction in total costs per patient over five years.[20]

- collaborative case management by a medically supervised nurse, with the goal of controlling risk factors associated with multiple diseases, improved control of medical illness and depression outcomes in patients with depression and diabetes and/or coronary heart disease.[21]

The collaborative care model provides an evidence-based framework for sharing responsibilities between GPs and specialists UK-based examples of innovative service delivery include the Primary Care-based approach to mental health adopted in Sandwell, which focuses on wellbeing and delivery of upstream and psychosocial interventions. The approach is a federated one, including Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) but also extending beyond this to include a range of other service providers. Key components include:

- a single point of mental health referral for GPs, health visitors, midwives and other professionals, which asks patients which of a menu of services they would like to access

- a tiered approach – people are assigned to one of five different levels of severity, with a different menu of services available at each

- a focus on wellbeing throughout all services – with success defined in terms of meeting a person's self-defined emotional and social needs more than in terms of clinical symptoms and definitions. This is driven by measuring wellbeing and mental health outcomes using standardised tools

- bottom-up service redesign based on extensive community engagement

- systematically mapping community and public service assets and building capacity in local charities and community groups, so that these are increasingly organising into a more federated entity able to provide a range of services

- building a culture of independence, by teaching problem-solving and self-management skills, and through use of peer support and social prescribing

- transforming libraries into community hubs providing a range of health and wellbeing services and self-help resources

- care management for people with complex needs.

Collaborative care could be supported through a variety of organisational approaches.28 29

- a single integrated care organisation providing both Primary Care and specialist mental health services

- shared care arrangements between a Primary Care provider and a mental health provider, with mental health staff embedded in Primary Care settings

- a facilitated referral approach where a care manager ensures co- ordination of care delivered by Primary Care and mental health professionals, but without physical co-location of staff.

Older Adult Mental Health Services

Home-based models of care are especially effective for service users with multiple diagnoses and comorbidities with a high risk of hospitalisation[22]. The UK all party parliamentary group on dementia document "The £20 billion question" stated that at any one time up to a quarter of general hospital beds are occupied by people with dementia. For Jersey this would equate to about 50 service users at the general hospital having a dementia at any one time, although dementia would not necessarily be the reason for admission. It is widely accepted that many of these admissions could be prevented if individuals and their carers were better supported at home. The challenge is to ensure that any new service model gets to the heart of the unmet needs.

Evidence supports early diagnosis and intervention in improving quality of life and delaying unnecessary admissions into hospitals and care homes[23]. In addition to diagnosis, the Memory Assessment Service will provide information, and direct medical, psychological and social support for people with dementia and their family carers.

Analyses suggest[24] that the service needs only to achieve a modest increase in average quality of life of people with dementia, plus a 10% diversion of people with dementia from residential care, to be cost-effective.

NICE guidelines state that "People with dementia should have an assessment and an ongoing personalised care plan, agreed across health and social care, that identifies a named care coordinator and addresses their individual needs."

The evidence for Liaison is also strong - an innovative project in the West Suffolk and Ipswich Hospitals[25] provided improved support to the acute hospitals for service users presenting with delirium and dementia, including the appointment of specialist nurses and health care support workers. The project found that when working closely with mental health liaison services readmission rates reduced by 70%. The Leeds Liaison service follow-up study revealed that the average length of stay within the acute hospital for people with dementia fell by 54% from 30 to 13.9 days saving 1,056 bed days per year. This is supported by the BMA written evidence to the All Party-Parliamentary Group on Dementia who stated "with 300 referrals per annum (to old age psychiatry services), there is a potential saving of 1500 days waiting per acute hospital, if only half of these service users discharge planning were delayed as a result of waiting for a psychiatric opinion then this would equate to 750 bed days".

Forensic Mental Health Services

The core purposes of all forensic mental health services are to:

- treat individuals with mental disorders (including neurodevelopmental disorders) who pose, or who have posed, risks to others and where that risk is usually related to their mental disorder

- provide this treatment in community, hospital (particularly secure hospitals) and prison settings in line with the principles of a recovery- based approach

- provide treatment aimed at managing mental disorder and reducing risk to others and offending behaviour

- advise and work collaboratively with other mental health professionals, GPs and social care staff – providing specialist risk assessment and management advice on community patients who demonstrate a risk of serious harm to others (perceived or actual), with the aim of reducing risk and avoiding the need for admission to secure care

- give expert advice to, and work with, other criminal justice system agencies to manage risk for individuals with (or thought to have) a mental disorder – this is usually via a Multi-Agency Public Protection Arrangement (MAPPA), which includes police officers, prison staff and probation officers

- provide services to the criminal justice system (these are expected to fit with the 'Criminal Justice Mental Health teams envisaged by the Bradley Report

- provide evidence-based assessment and treatment that will rely on education and training provided by forensic mental health services

- support research and audit within services.

The model of forensic mental health care is based on an integrated pathway which is comprised of numerous service components. Within the Care Pathway there should be:

- clear care pathway for each patient from admission to discharge from secure care

- integrated services dependent on patient identified needs and through whatever levels of security are required

- that there is seamless progress along the pathway, even when this is through different levels of security or different providers of care

- that needs are being regularly reviewed and care plans in place to meet those identified needs

- that there is an expectation that the patient's needs will change as they move along their care pathway

There should not be an expectation that all patients must descend' through all levels of security (i.e. high, medium, and low) prior to discharge.

Different services will have different processes to manage the pathway of care (with case managers alone or working with clinicians). They should ensure that, even when specific packages of care are commissioned, these are not delivered in isolation. They should be an integrated part of the patient's care pathway.

Appendix A

![]() Priority1: Social Inclusion & Recovery

Priority1: Social Inclusion & Recovery

What we said we People working in mental health services will agree a common would do approach to help people continue their recovery and help them

learn to live with their diagnosis and continue to play a full and

active part in their community, parish and Island.

Continue to raise awareness of mental illness in the local media and stand up to discrimination and stigmatisation of people who experience mental illness.

What we have done Established a Mental Health Citizens Panel.

- Established a Jersey Recovery College.

- Developed an integrated Suicide Prevention Training programme for professionals.

- Enhanced the Jersey Online Directory.

- Continue to raise awareness of mental illness and services

available.

- Older Adult Primary Care Mental Health Team established with focus on links with Primary care, re- ablement and social prescribing.

Next Steps Continual awareness raising of mental health to reduce

stigma.

- Implement a Community Network.

- Hold a Jersey WellFest public event on the 27th October 2018.

![]() Priority 2: Prevention and Early Intervention

Priority 2: Prevention and Early Intervention

What we said we would do Build preventative approaches used in schools to support

students to look after their emotional wellbeing, in the

same way as they look after their physical health.

Reducing waiting times for the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service (CAMHS) improve the quality of this service for those with specialist needs.

Improve the way we identify, treat and support people living with dementia.

What we have done Commenced Primary Mental Health workers in schools.

- Enhanced Memory Assessment and Early Diagnosis – Primary Care Mental Health Team, enhanced all-age multi-disciplinary memory assessment service, and

Older Adults Mental Health Hospital Liaison service.

- Enhanced Mental Health Liaison for people with

dementia.

- Established Primary Care Mental Health Service for older adults

Next Steps Jersey WellFest (year 7 students only) event on the 26th

October reaching in to schools.

- CAMHS Transition

![]() Priority 3: Service Access, Care Co-ordination and Continuity of Care

Priority 3: Service Access, Care Co-ordination and Continuity of Care

What we said we would do More mental health services into GP surgeries to make it

easier for people to obtain help.

Improve services to make them more able to respond quickly to people living at home and thereby avoid unnecessary hospital admissions.

Providing mental health services for groups who we know have high levels of need

What we have done A review and gap analysis of criminal justice mental

health service.

- Established a forum with professionals from Mental Health and Criminal Justice Services.

- Community Triage Pilot.

- Feasibility Study and Strategic Outline case for

Estates.

- Care Close to Home introduction of 2 Mental Health Nurses to Rapid Response and Re-ablement Team for older people.

- Collaborative links and joint work with Jersey

Alzheimer's Association.

- Series 6 Training to police probation and prison

Next Steps 24/7 Crisis Response Team

- Implement all the recommendations from the gap analysis to design integrated pathway

- Place of Safety

- Multi-disciplinary teams for adult mental health in GP surgeries(Primary Mental Health Care)

- Develop a pathway for forensic medium and low secure mental health inpatient services

- Develop asset management plan for mental health estate

- Develop future housing options for people with dementia – plan to develop as part of the Dementia Strategy.

- Assistive technology (telecare) to service users and their carers

- Develop Care Closer to Home services

![]() Priority 4: Quality Improvement and Innovation

Priority 4: Quality Improvement and Innovation

What we said we would do Publish a set of measures for the public that describe the

quality of our mental health services.

Publish a set of measures for the public that describe how our mental health services are performing.

Workforce development

What we have done A defined set of Mental Health outcome measures.

- Signed up to the NHS benchmarking.

- Recruitment Campaign.

- MSNAP accreditation for Memory Assessment

Service

- Develop a workforce strategy.

Next Steps Continue to publish annual reports about performance.

- Develop a robust Quality Assurance and Governance system.

- Implement the Workforce Strategy

.

![]() Priority 5

Priority 5

What we said we Routinely ask service users to help us to improve services. would do

Use information about how our services work to help us improve services, achieving better value for the funds that are invested.

What we have done Established a Mental Health Implementation Group.

- Involving service users to ensure co-production when designing services.

- Development of two monthly forums for people who use memory assessment services – younger onset and older

pathway.

- Jersey Talking Therapies (JTT) improvement workshops – Co-production.

- Engagement Days bringing all together.

- Communicate progress to key stakeholders.

- Established an integrated communication group for

various awareness days.

Next Steps

- Continue to involve service users to ensure co-production when designing services.