The official version of this document can be found via the PDF button.

The below content has been automatically generated from the original PDF and some formatting may have been lost, therefore it should not be relied upon to extract citations or propose amendments.

Stewarts' Response to the Scrutiny Review of the Draft Damages (Jersey) Law 201-

About Stewarts

Stewarts is an international litigation firm specialising in complex high value disputes. Our practice areas include Personal Injury, Clinical Negligence, International Injury and Aviation.

Within these practice areas, the claims we undertake exclusively relate to injuries of the utmost severity or death. Our specialisms are recognised by top-tier rankings in the leading legal directories, Chambers, the Legal 500 and the Times.

Whilst there are many firms of solicitors which do some complex and high-value personal injury litigation, we are one of very few firms in the UK that exclusively specialise in such claims and do not conduct claims relating to non-disabling injuries (aside from the rare scenario when there are secondary claimants involved in the same incident as a claimant with severe injuries). We are well-placed to provide a response to this consultation, as almost all our cases involve issues surrounding periodical payments orders and the inevitable contrast with a lump sum award applying the discount rate. We acted for the Claimants in a number of the leading cases concerning periodical payments[1] and concerning negative discount rates in Bermuda[2].

We take the opportunity to point out that we are a relevant stakeholder for this review on the basis we have and continue to represent a number of Jersey based clients and this review, together with this response, are made in their interests. We work in conjunction with Jersey co-counsel David Benest at BCR Law in representing our Jersey clients.

Julian Chamberlayne, Partner and Head of International Injury acted for the plaintiff, in the case of X v Estate of Y (Deceased) & oths heard in the Royal Court of Jersey, Samedi Division (2013/143), a polish citizen injured in a road traffic accident in Jersey. We were able to obtain the first PPO in Jersey in this case.

In addition, we have two current catastrophic injury cases running in Jersey[3] in which our expertise is required to ensure those clients have the best chance of obtaining the correct level of compensation.

Accordingly, our submission has a particular focus on the impact of the issues raised by this review on those with seriously disabling injuries, with reference to those Jersey cases mentioned above.

We attach the following documents to assist in interpreting our comments below:

- The Discount Rate – a report for the Ministry of Justice prepared by Paul Cox, Richard Cropper, Ian Gunn and John Pollock. Dated 7 October 2015;

- PFP – MoJ call for evidence; and

- Stewarts Discount Rate Calculation example.

Wells v Wells approach and ILGS

It is accepted within the Draft Damages (Jersey) Law ("Draft Law") that Jersey's courts have generally adopted English common law'.

In our view, the English common law approach determined by the House of Lords in Wells v Wells remains the fairest and best way of meeting the full compensation principle.

In his leading speech in the House of Lords, Lord Lloyd of Berwick stated that the judges in the three jointly heard cases of Wells:

"were right to assume for the purpose of their calculations that the plaintiffs would invest their damages in I.L.G.S. for the following reasons:

- Investment in I.L.G.S. is the most accurate way of calculating the present value of the loss which the Plaintiffs will actually suffer in real terms.

- Although this will result in a heavier burden on these defendants, and, if the principle is applied across the board, on the insurance industry in general, I can see nothing unjustNo doubt insurance premiums will haveto increase in order to take account of the new lower rate of discount

- The search for a prudent investment will always depend on the circumstances of the particular investor. Some are able to take a measure of risk, others are notStill less is it his duty to invest in equities and gilts in order to mitigate his loss.

- How the plaintiff, or the majority of plaintiffs, in fact invest their money is irrelevant. The research carried out by the Law Commission does not suggest that the majority of plaintiffs in fact invest in equities and gilts but rather in a building society or a bank deposit"

The Wells approach was validated by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in Simon v Helmot with Lord Hope explaining at paragraph 47 that:

"finding a solution today is not so dependent on surmise and speculation as it was when the issue was being discussed in those cases three decades agoThe investment scene has been radically altered. The breakthrough came with the introduction of ILGS and the appreciation that there was at last a tool that could be used to provide protection against inflation. It is tailor-made for investors who want a safe investment for the long term. In practical terms that is risk free. As nearly as possible, it guarantees the availability of the money to meet costs as and when it is required. It may not be perfectBut it is the best tool that is available."

In the Draft Law, in line with the Ministry of Justice's (MoJ) 2017 consultation paper, a heavy emphasis is placed on investment return and investment risk. However, as Lord Hope's explanation suggests, the impact of inflation is equally as important. One of the reasons for adopting ILGS as a proxy return on which the discount rate should be derived was the difficulty courts otherwise faced in predicting future inflation. In the Court of Appeal case of Helmot, Sumption JA (as he then was), commented, stating at paragraph 38:

"The reason for calculating a lump sum award on the footing that the lump sum will be invested in index-linked gilts is that it achieves an automatic adjustment for future increases in the general level of prices."

The MoJ's 2017 consultation was right to acknowledge that it is essential for the discount rate to be set in a manner that fairly represents the 100% compensation principle. This echoes the MoJ's 2013 consultation on discount rate where it was noted at paragraph 6 of that paper that:

"if the rate is too high, the burden would fall on the victims of the wrongful act, who include some of the most vulnerable members of society, who would be under- compensated, thereby possibly increasing their reliance on the state and, therefore increasing costs to the taxpayer."

Underlying that observation and the points made by Lord Hope in Wells is the simple concept that the cost of meeting the long-term losses and needs of those seriously injured by the wrongful acts of another party may fall to a combination of the following:

- The injured party;

- The party who caused the injury or more commonly their insurer; and

- The State/taxpayers.

It is clearly appropriate for the party who caused the wrong, creating the loss, to be responsible for the financial consequences. Where those losses continue into the future, the resultant financial risk as to how those losses should be met in the long-term should be borne by the wrongdoer. There is no sound argument in principle as to why either the loss or the risk of meeting the long-term needs should fall to the injured party or to the State/taxpayer, unless of course the State is the wrongdoer.

The adoption of a discount rate based on ILGS does not lead to the single Claimant being "over compensated". Rather, Claimants may choose to take investment risks so as to attempt to improve their financial position. To require them to do so, however, as is contemplated by this Draft Law, would make them the only class of investor required to take risk so as to advantage some other party (the wrongdoer/the wrongdoer's insurer). This cannot be considered either fair or just. In reality most seriously injured Claimants base their decisions on investing their damages around meeting their disability needs and very few seek to take investment risks to outperform their needs.

Proposed Statutory Discount rates of +0.5% and +1.8%

We strongly oppose the introduction of statutory discount rates, to be set at +0.5% and +1.8%, because such rates would not satisfy the full compensation principle and the basis for proposing those rates is inherently flawed. The key reasons why we are of this view are:

- reliance on the model portfolios from GAD report 2017;

- emphasis on the investment decisions assumed to be made by individual Claimants;

- allowance for investment management charges and tax;

- The proportion of claimants who will be under compensated utilising a mixed portfolio approach is inconsistent with a full compensation regime;and

- The dual rate split: the Ontario Model and earnings related model.

- Reliance on themodel portfolios from GAD report 2017

The Draft Law relies on the GAD report 2017 which followed the 2017 MoJ consultations; we refer to our 2017 consultation response to the MoJ which has been provided with this response.

The MoJ asked the Government Actuary Department ("GAD") to analyse two model portfolios based on unpublished anecdotal reports of claimant investor behaviour. Portfolio A was considered to reflect typical low-risk' claimant behaviour, whereas Portfolio B was the highest end of the low-risk' spectrum. They were not asked to and did not analyse the lowest end of the spectrum. Therefore, not only are the conclusions on which the MoJ proposes this legislation is passed derived from an unpublished and small evidential base, they also do not reflect the full range of claimant investor behaviours.

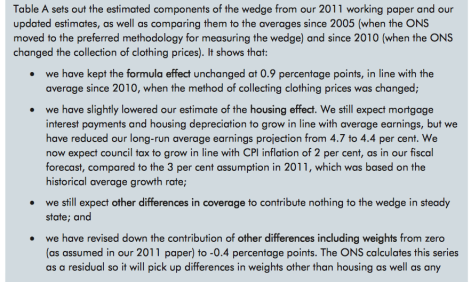

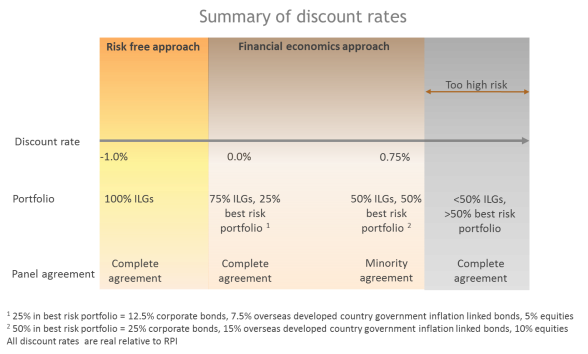

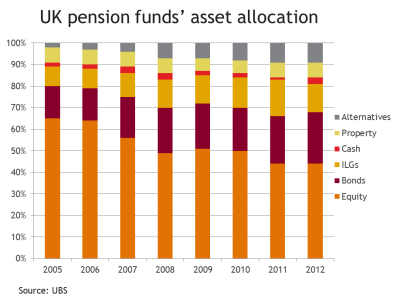

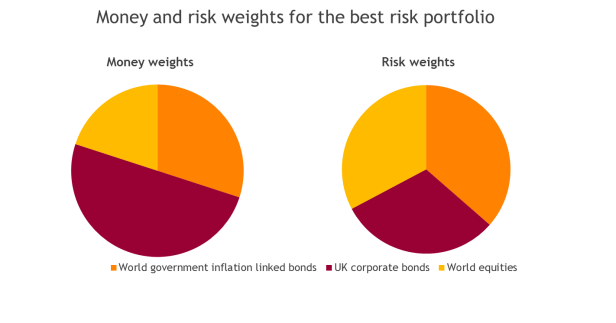

Additionally, the low-risk' categorisation of the portfolios modelled by the GAD is disputed on the grounds that both models carry a serious risk for the claimant's ability to achieve full compensation. According to the GAD model, Portfolio A had just 5% invested in ILGS (with 46% in equities or alternative investments) and this figure was only 3% in Portfolio B (with circa 65% in equities or alternative investments). In contrast, the majority of the 2015 MoJ expert panel (the full report has been provided alongside this response) described the low-risk portfolio approach as one in which at least 75% of the portfolio is allocated to ILGS.

In preparing this response we have sought the views of 2 of the authors of that expert report: Richard Cropper and Ian Gunn. They have confirmed that they stand by the view that no account was taken of the fact that any claimant investment behaviour was in light of the need to hedge mortality risks, the impact of having insufficient capital following the purchase of a property (due to the Roberts v. Johnstone approach to future accommodation giving rise to a capital shortfall), earnings (rather than price inflation), taxation and active investment charges.

Personal Financial Planning (member of the MoJ's expert panel) have repeatedly warned that if one is to take account of real-life experience, that must be in respect of both claimants' liabilities to real earnings growth, taxation and investment charges, as well as the return on investing in a mixed portfolio.

By only looking at what claimants invest in and not why they are forced to invest in those assets, the discount rate is bound to be set at too high a rate, as claimant will have to invest with exposure to even more risk to cover real earnings growth, taxation and investment charges.

- Emphasis onthe investment decisions assumed to be made by individual Claimants

The House of Lords in Wells v Wells, as followed by subsequent courts who have considered the issue of whether ILGS is the best tool by which discount rate could be determined, have renounced the proposition that it was based on how Claimants choose to invest their compensation. The utilisation of ILGS as the benchmark is only ever a pragmatic proxy for the net real rate of return. It created a fair and predictable method by which future losses could be calculated that was not reliant upon expert evidence. It did not require speculation about the composition of any investment portfolio, the returns on the portfolio, the level of charges of investment managers and stockbrokers, the level of taxation nor a prediction of future inflation.

An individual Claimant's decision to take an investment risk is clearly their choice and a matter only for them. If their investments go well and they out-perform the discount rate, then their financial position is enhanced. However, that is as a result of the investment decisions/risks they choose to take after the conclusion of their case, coupled with the good fortune of those investment risks working out in their favour. If a Claimant who makes numerous risk-based investments were to achieve poor returns or actual losses, it would result in a performance below the discount rate and ultimately lead to compensation running out during his or her lifetime. There is nothing in law, currently, which would allow for him or her to return to the Defendant who caused their injury to seek further compensation. Once again, this potential outcome is a consequence of the risk the Claimant chooses to take in relation to any investments. The law should not be constructed in such a way that either forces the Claimant to take those risks, or requires them to do so for the benefit of the party who caused their losses in the first place.

We endorse the following points made by Personal Financial Planning[4]: that in their experience Claimants (1) do not invest in risk assets with the aim of maximising returns in order to generate over compensation that they can spend on wants' rather than needs', and (2) sometimes accept risk in order to facilitate the maintenance of their needs over time, often having also looked at family support to create a saving on care costs, state support and compromising or foregoing needs.

- Allowance for investment management charges and tax

It is essential to make full allowance for administration, management expenses, investment advice and the costs of purchasing and selling investments (both initial costs and subsequent changes). The need for such adjustments have been consistently acknowledged by GAD and the MoJ, but the level of the adjustment has not yet been determined nor applied to the modelling conducted by GAD.

Our Mr Chamberlayne, in his role as Chairman of the Forum of Complex Injury Solicitors (FOCIS) has been gathering data on this point from UK firms who regularly act as Deputy and/or Professional Trustee for seriously injured Claimants who have received substantial damages awards. We append a summary of the preliminary conclusions of an analysis of that data by Ian Gunn of PFP as recently submitted to the MoJ and GAD. The broad indication from that data is that overall costs, including investment advice, tend to fall in the range 1.5% to 2%. This is materially higher than the 0.5% figure tentatively suggested by GAD in their 2017 report for the MoJ. It is within, but at the upper end, of the range the GAD referred to in their 2018 report to the Scott ish Parliament. Note that this data did not include the impact of tax on the investment return, as that impact varies considerably between Claimants based on their personal circumstances, but GAD accept that a further adjustment for tax is necessary. This may be achieved in crude terms by rounding up rather than down, until someone conducts the research to enable a more informed adjustment to be made.

In this summary Ian Gunn adds:-

"I should point out that the costs set out above are incurred by claimants in managing cash flows and risk, selecting what to buy and what to avoid, when to sell, holding and keeping track of investments, the income they generate, capital gains and capital losses, and all regulatory compliance. They are not performance fees, i.e. payments to an investment manager in the expectation of achieving superior returns compared to a benchmark, so that the investor ends up better off than without active investment management".

It is essential that the adjustment for all aspects of investment management charges and tax is made to ensure the resultant discount rate reflects the likely net return that these Claimants will achieve on a low risk basis. The alternative is that the law would need to be changed to make such costs a recoverable head of damages. However we contend that is a less satisfactory approach as it will inevitably lead to disputes in many claims.

- The proportion of claimants who will be under compensated utilising a mixed portfolio approach is inconsistent with a full compensation regime

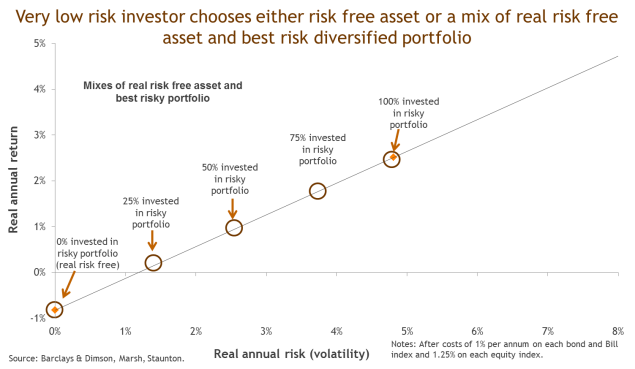

As strong advocates of the Wells v Wells approach, we are of the opinion that the assumed investment risk profile of the Claimant should be assumed to be that of very risk averse or "risk free".

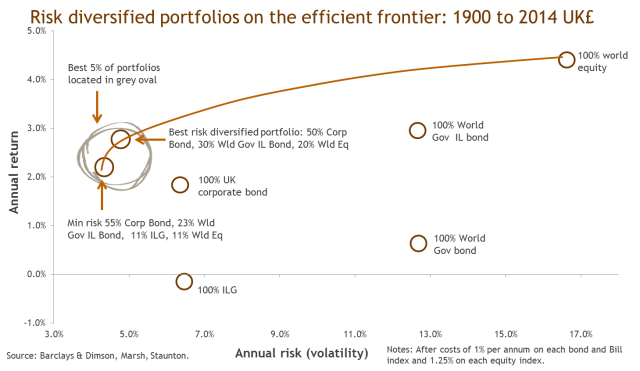

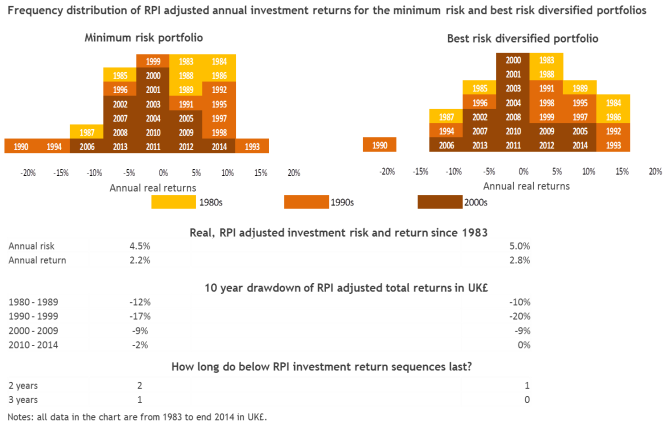

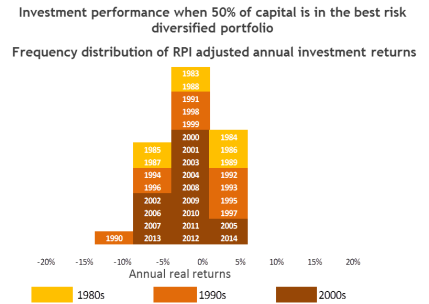

These issues were previously considered and addressed in a 2015 expert report commissioned by the Ministry of Justice. The appointed panel of experts, consisting of Paul Cox, Richard Cropper, Ian Gunn and John Pollock, came to the majority view that the discount rate should continue to be based on the Wells approach. The panel cautioned that if the approach of a mixed portfolio balancing low risk investments were to be taken (category b), then only up to 25% of that portfolio should be allocated to non- risk-free assets. The modelling also demonstrated that if the approach were adopted, the discount rate would be 0%.

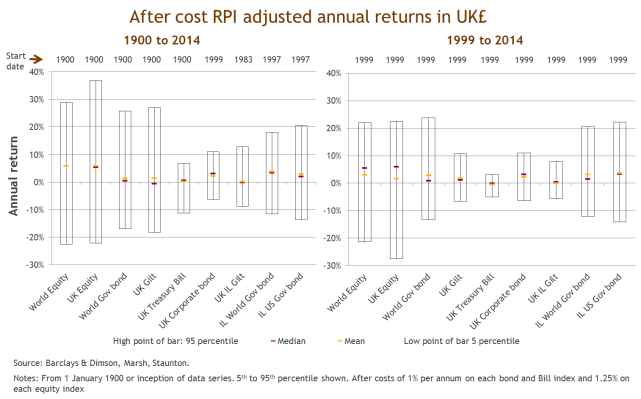

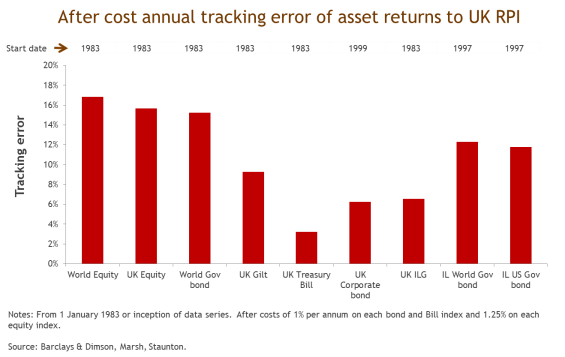

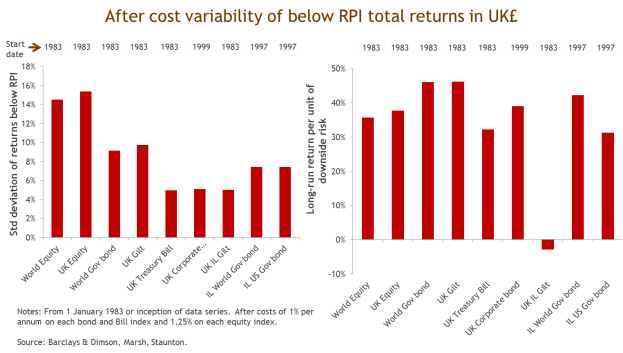

The majority of the panel did, however, emphasise that having reviewed Dr Cox's research on the modern portfolio theory, the emerging risk measures appeared to be inconsistent with the requirement for the portfolio to be considered very low risk. This analysis highlights the very significant deviations that could arise even with a low risk or very low risk mixed portfolio. They could cause a significant proportion of Claimants to be undercompensated and hence leave them unable to meet their needs.

In the Bermuda case of Thomson v Thomson and Colonial Insurance Company Limited, similar issues can be described as having arisen. At first instance in the Supreme Court of Bermuda, Chief Justice Kawaley observed at paragraph 38 that the case appeared to be the first occasion in which a common law court has been required to consider, in the future damages discount rate assessment context, the respective merits of an assumed investment of the entire lump sum to be awarded in ILGS as opposed to in a mixed basket of investments. The Defendants in that case had relied on the expert evidence of

a Canadian Actuary, Christopher Gorham, who advocated a mixed portfolio moderated with what he described as a "safe fund". This was similar in concept to the financial economics approach that is advocated by Dr Cox and considered by the other members of the Ministry of Justice's expert panel back in 2015. This mixed portfolio was also broadly comparable to the "low risk" portfolios that feature in the GAD 2017 report to the MoJ. At paragraph 93 of the Thomson Judgment, it was observed that Mr Gorham: "conceded under cross-examination by Mr. Harshaw that on his investment model between 50 and 33% of plaintiffs would not have sufficient funds. He viewed his approach as fair to both claimants and defendants."

Chief Justice Kawaley commented:

"I viewed his approach as a stunning dilution of the prevailing legal policy preference, in the future loss discount rate calculation context, for a hypothetical investment in an instrument likely to generate a risk-free rate of return."

At paragraph 100, Chief Justice Kawaley also made reference to the evidence of the Claimant's Actuary, (former Government Actuary), Christopher Daykin, as follows:

"As Mr. Daykin explained, institutional investors are able to safely invest in a wider range of investment instruments because they are investing on behalf of multiple ultimate investors whose needs to redeem their investments stretch out over multiple lifetimes. Such investors are also able to hedge against short-term risks in ways which are generally impossible for the typical individual personal injury Claimant. I find that there is a fundamental distinction between the investment goals of the hypothetical prudent investor, especially an institutional investor, (who is not investing sums received by way of compensation for tortious injury), and the investment goals of the hypothetical prudent plaintiff. As regards the latter, there are explicit legal policy imperatives which require the courts assessing the appropriate level of lump sum to award to:

- assume that the least possible risk will be taken when the lump sumis invested by the prudent Claimant with a view to achieving the goal of full compensation;

- ignore the commercial realities of how lump sums may actually be invested; and

- utilize tools for the calculation of the discount rate which are sufficiently simple to be conveniently deployed both in the context of assessing damages in and out of court without the need for the expense of expert evidence save in exceptional cases."

The Bermuda Court of Appeal subsequently fully endorsed the Judgment of the Chief Justice.

At paragraph 23, Bell JA commented further that:

"What Mr. Daykin was saying is essentially that Mr Gorham's theory of sufficiency demonstrated that, using his model, there is approximately a 50% chance of a Claimant receiving a fund sufficient to meet expenses and losses, with the other side of the coin being that 50% of Claimants would not have sufficient assets to do so. Consequently, Mr. Daykin concluded that these figures come nowhere near meeting the principle of full compensation which has been accepted over many years by the courts. What Mr. Daykin said in relation to the 90 to 95% figures was not that these represented over- compensation on the basis of the Chief Justice's ruling, but that if one were to test a model proposed in place of the Wells mechanism (as advocated by Mr Gorham), then

there would have to be a demonstration that the payments were sufficient for the Claimants in at least 90 to 95% of cases in order to come close to providing full compensation."

The Ministry of Justice's expert report in 2015 does not appear to have directly addressed the question of sufficiency, this being the percentage of Claimants who would, under the alternative portfolio models proposed by Dr Cox, end up with insufficient assets to meet their future needs. However, reading between the lines in relation to the panel of experts' comments concerning the similar concept of deviation, a significant proportion of those Claimants would end up with insufficient funds. This no doubt led the majority of the panel to come to the conclusion that it was an inappropriate way for calculating the discount rate.

In the GAD 2017 report they acknowledged that the need for the MoJ to consider the issue of what level of under compensation was acceptable within a full compensation regime then make any necessary adjustment to the figures derived from their modelling before setting the discount rate. This issue was echoed in the Justice Committee's Report, published 30 November 2017, in particular paragraphs 22 -24.

The sufficiency question was posed by us to Wrigleys Solicitors and Fensham Howes, firms which routinely advise Claimants on long-term investment following the resolution of their litigation. They both indicated that when considering low risk investment portfolios for their seriously injured clients, they tend to strive for a sufficiency ratio of 90 to 95%. In doing so, they take account of the life expectancy risk to try and ensure that Claimant funds would last to the upper end of the range of probable ages. Fensham Howes' approach to investment is based upon years of research which has repeatedly shown that the perfect investment offering both low price volatility and high long term returns above inflation does not exist.

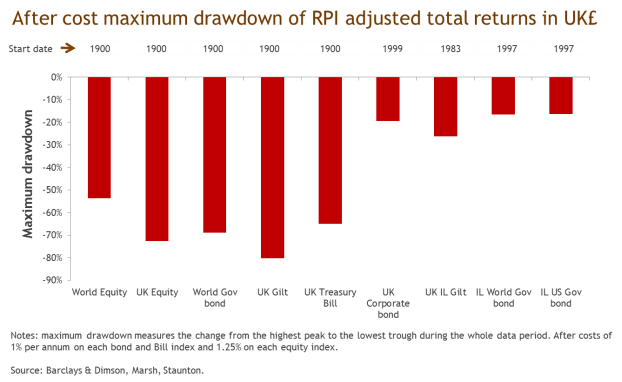

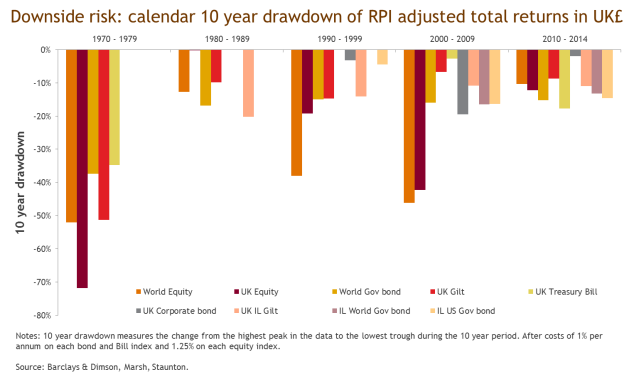

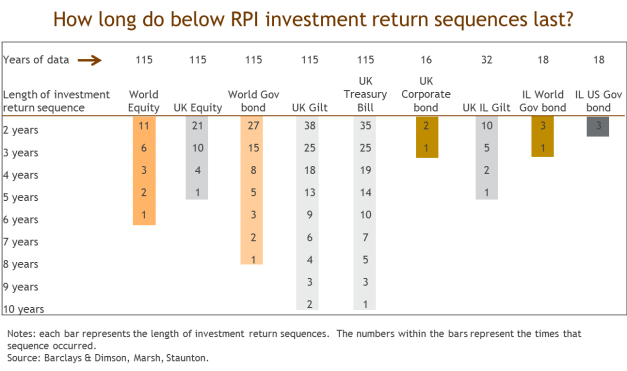

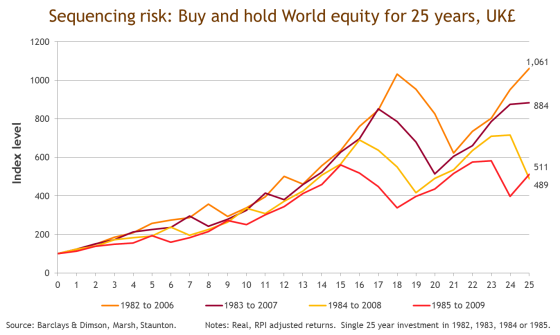

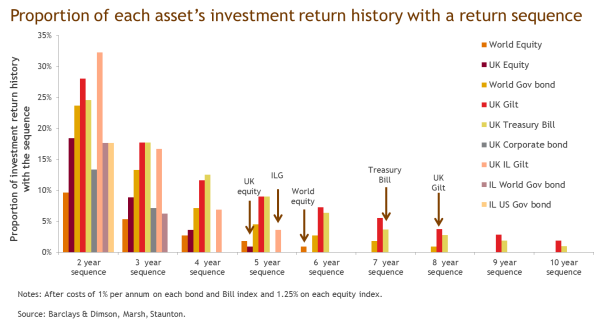

Due to the boom and bust cycle of the economy the uncertainty caused by this lack of stability means that if a Claimant is in need of funds when the market is low, it will adversely affect his remaining award to his/her detriment and could therefore leave them reliant on the state when the money runs out. This volatility, as outlined in the expert report prepared for the Ministry of Justice in 2015, creates a sequencing risk "which occurs where one year of below RPI investment returns is immediately followed by another, which is immediately followed by another etc. Poor investment return sequences combine with portfolio withdrawals in a highly destructive way because more fund units need to be enchased [sic –encashed] to generate the same annual income. The double erosion of capital following a market fall -the market drop and the drawing an equal income at depressed fund value -is what makes sequencing risk potentially destructive One of the lessons of the technology boom and bust followed shortly by the financial crisis was the importance of the order, or sequence, of extreme investment returns. If a sequence of market drops means the capital of a fund is 50 per cent lower than planned, a 100 per cent gain is needed to return the fund to where it should be"[5]

- The dual rate split: the Ontario Model and earnings related model

The Draft Law refers to the UK GAD's analysis and proposes Jersey statutory discount rates of +0.5% up to 20 years and +1.8% applicable to all the years where the loss is deemed to be for a period of over 20 years. The proposed rates and the use of a form of the Ontario model, in splitting periods, lacks adequate supporting analysis for either the 20 year period or the proposed rates. We understand that the 1.8% discount rate is a hybrid of Portfolio A and B over 30-50 year period but we strongly believe this is flawed for two reasons. First, claimants are likely to have a shorter investment life than a composite of 30-50 years. The only claimants that would have an investment life of that length of period would be minors. Since the beginning to 2016, only 3% of Stewarts' PI cases involved minors, therefore the assumption regarding investment period is inappropriate. Secondly, as discussed above, the Portfolio A and B contain 46% and 65%, respectively, in equities and alternatives and therefore cannot be considered a sufficiently low risk portfolio appropriate for claimants. Furthermore, if the Draft Law were passed as proposed, it appears that a Claimant with a loss spanning 19 years would receive more compensation that one of a little over 20 years, as evidenced below:

That is clearly perverse.

We contend that the more important issue is there are to be differential discount rates is to provide full compensation for earnings-related heads of future loss, notably loss of earnings and future care and case management. It is also applicable to other earnings- related heads of loss, such as the cost of a Professional Deputy and medical professionals including therapists.

The impact of earnings inflation and the need for an adjustment has already been closely scrutinised and accepted in the context of a periodical payment regime as reflected by the Court of Appeal Judgment in Flora v Wakom (Heathrow) Limited and Thompstone v Tameside. This has resulted in the general practice thereafter being to apply ASHE 6115 indexation to PPOs for care and case management and less frequently, other earnings- related indices for other earnings-related losses.

The application of this adjustment to lump sum compensation has been considered by the Guernsey Court of Appeal (in the highly regarded Judgment) of Sumption JA (as he then was) and the Privy Council. It has also been considered by the Chief Justice of Bermuda, and subsequently endorsed by the Court of Appeal in Bermuda in Colonial Insurance Company Limited v Thomson (conjoined with Harvey v Warr en).

Lord Hope in the Privy Council Judgment concerning Helmot v Simon quoted favourably from the Judgment of Sumption JA as follows:

"if an adjustment could be made which would serve to compensate the respondent more exactly for his losses there was no legal reason why it should not be made" (paragraph 40) and "having considered the evidence, Sumption JA said that it seemed to him to constitute strong unchallenged evidence of both the existence of a gap between price and earnings inflation in Guernsey of the order of 2%, and the likelihood that over time it would persist" (paragraph 41).

"As for the question whether there should be more than one rate this seemed to him to be correct in principle in a case where there was a significant difference between elements representing loss of earnings and care costs" (paragraph 42).

Lord Hope's conclusion, strongly supported by Lord Brown at paragraph 75, was that: "75. if this Claimant is compensated for future loss only on the basis or projected RPI inflation, his award (intended to compensate for increased future losses over the period for his predicted further lifespan of 40 years) will almost certainly prove inadequate to meet his long-term future care needs.

- The real question in the Appeal must therefore be this: Which approach is preferable: one which ignores the established claim showing an increase in real earnings and so produces an award of almost certainly less than will be sufficient to meet the Claimant's likely future care costs, or one which uses the best available evidence

- The answer must therefore be obvious."

Lord Brown at paragraph 82 referred to Sarwar v Ali and oths in which Lloyd Jones J accepted what he described (at paragraph 143) as:

"A consensus between the experts that the RPI is not an appropriate index for Periodical Payments in respect of future loss of earningsThe same is true of the future cost of care and case management."

Finally and pithily from the Helmot Judgment, Lord Dyson at paragraph 113 said:

"There can be no justification for holding that, on these admittedly bare and rather crude facts, damages should be assessed using a discount rate based on RPI inflation. Such an assessment would be bound to lead to under-compensation."

In Sarwar v Ali & the MIB, the Defendant did have an Economist, a Mr Cooper. At paragraph 142 of the Judgment, Lloyd Jones J stated:

"there is near unanimity on the part of the experts in relation to certain of the issues. Dr Wass (Economist), Mr Hogg (Accountant), Mr Copper (Economist) and Mr Hall (Accountant) all agree that average earnings generally increase at a faster rate than prices, that on the balance of probabilities average earnings growth is likely to exceed growth in prices in the future and that, on the basis of historical data, linking Periodical Payments to loss of earnings for RPI would be very likely to undercompensate the Claimant."

At paragraph 161, he observes that:

"She (Dr Wass) concludes that all the measures of earnings growth which she examines exceeds the corresponding measures of growth in pricesShe concludes that measures of earnings growth in the care sector have consistently exceeded the growth in aggregate earnings over the period 1998-2005."

The Judge then quoted from the evidence of the Claimant's Accountant, Mr Hogg, which had confirmed that:

"For the whole period 1963-2006 earnings (AEI) increased on average at 1.9% per annum faster than prices (RPI) but over the last 20 years the rate increase has been lower at 1.53% above price inflation as mentioned by RPI."

The Judge noted at paragraph 163 that:

"Mr Cooper and Mr Hall agree that there is a longstanding pattern showing average earnings rising faster than price inflation."

At paragraph 166 Lloyd Jones J dismissed one of the Defendant's counter-arguments, being:

"wholly unpersuaded by Mr Cooper's arguments based on the possibility of improved productivity in the provision of care for the Claimant in the future."

He observed that was not supported in any way by the care experts.

As can be seen, when this issue has been closely analysed by the courts, the evidence in favour of making an adjustment for earnings-related heads of loss was on each occasion considered overwhelming and required to achieve full compensation. The evidence demonstrated that the scale of the adjustment required tended in the long-run to be between 1.5 and 2%. This would mean it is necessary for there to be a differential earning related discount rate that is between 1.5 and 2% lower than the general (prices) discount rate. This would ensure that the full compensation principle is adhered to and avoid manifest unfairness, notably to those Claimants for whom a Periodical Payment for those heads of loss was wholly unavailable, not offered by the Defendant, or not appropriate for a variety of other factors.

We note that there has apparently been a more modest earnings inflation differential in Jersey in recent years. The short timescale for responding to this consultation has meant we have not been able to scrutinise that phenomenon. It conflicts with the economic evidence advanced in all of the above mentioned cases concerning negative discount rates in Guernsey, Bermuda and Jersey[6]. However, rather than having this issue prescribed by primary or secondary legislation, we propose that the Courts be given a broad discretion to set a differential earnings related discount rate, if the evidence supports such a conclusion. This would be in line with the approach to the issue of the indexation of periodical payments for earnings related losses pursuant to the Damages Act.

Reverting to the concept of the different rates for different periods of time, our position is that we do not consider that to be either necessary or appropriate. We observe this concept was carefully considered and dismissed by the Ministry of Justice's panel of experts, with them commenting at their paragraph 6.7 that they were:

"not persuaded that the discount rate needs to vary by term of loss at the current time, if the discount rate was set by reference to ILGS alone, as the real interest rate yield curve is relatively flat over the long durations."

Fensham Howes, Financial Investment Advisers, emphasise that the risks Claimants face vary with investment time horizon, but do not inevitably, let alone predictably, reduce. For investors with short time horizons, volatility is the greater problem and this leads the prudent advisor to recommend portfolios with little or no volatility risk. Such portfolios will by nature contain a high proportion of low risk fixed income securities and will therefore have very limited potential for real growth above inflation. For investors with long investment time horizons, protecting against inflation is usually the greater problem.

The only common law Judgment which we are aware of in which an adjustment to the discount rate was varied by the term of loss is the Hong Kong case of Chan Pak Ting v Chan Chi Kuen et al. The Defendants in their above-mentioned Bermuda case of Thomson v Thomson and Colonial Insurance Company Limited urged the Bermuda Court to take a similar approach. It was a path adopted by the Defendant's Actuary, Christopher Gorham. However, as Chief Justice Kawaley in Thomson observes at paragraph 34:

"Chan Pak Ting must be understood in the context of its facts. There was a joint expert report and it was common ground that the ILGS measure was inappropriate as it was not even a potentially available instrument vehicle for the hypothetical reasonable Hong Kong Plaintiff. The vehicles taken into account were not selected as a more appropriate reference tool than ILGS but merely as the best available measure. The Hong Kong Court clearly considered the measures available as a "next best" rather than a "preferred" option."

A statutory introduction on Periodical Payment Orders in Jersey

In England and Wales, the Courts are required to consider, in all cases, whether to make a PPO. The Court can order a PPO even if the Claimant prefers a lump sum, where it is deemed to be in the Claimant's best interests (Sarwar v Ali & the MIB). Our experience is that virtually all UK insurers predominantly negotiate on a lump sum basis, often under Part 36 Civil Procedure Rules, carrying costs consequences for Claimants in failing to accept and fail to beat that offer. Many Claimants, who would prefer PPs, at least for future care, are often forced to settle on a lump sum basis as they are never given a PP based offer.

We fully support the introduction of PPO availability in Jersey, however the power to set the indexation applied to any PPOs should lie with the Courts. Leaving the power in secondary legislation, as is suggested in the Draft Law, is far too crude a measure, which risks falling out of step with use of PPOs. It is far more appropriate to grant the Courts wide discretion so that submissions can be made in individual cases insuring that the Claimants are fully compensated.

The Courts having the discretion to bespoke indexation of a PPO was crucial in the case of X v Estate of Y (Deceased) & oths, in which we represented the Plaintiff. If the PPO indexation had been set by secondary legislation, the PPO would have been entirely inappropriate considering that the Plaintiff is a Polish national who had returned to reside in Poland and consequently faced future losses that were not likely to rise in line with the Jersey economy.

Furthermore, if the indexation of PPOs were to be set by secondary legislation, it is not clear which index would be chosen. There appears to be three main options, being:

- Price indices, which we argue does not adequately reflect the overall economic trend to be suitable as the set benchmark for all heads of loss types;

- Jersey earnings indices, which is based on a relatively small group and also may have a high earner skew (due to the socio-economics of the jurisdiction), which may be unsuitable as a bench mark for carers earnings; or

- English indices, which are based on a sufficiently large sample group benefitting from the wealth of data from ONS as set out in the ASHE tables, notably those related to the earnings of carers. Thisis particularly important as the care claimis usually the largest head of future losses for those with serious injuries. If the indexation is inaccurate then over time the PPO will not provide for the cost of the claimants care claim and that phenomenon will compound year on year.

As shown in the above example, the setting of any of the above indices across the board would be inappropriate and would not sufficiently cater for all heads of losses. This issue is far better left to the judges to apply on the facts and evidence in each case, albeit as with the common usage of the ASHE 6115 index in England, it is likely that a few early court decisions will then establish a commonly applied norm.

What we would like to see in relation to the statutory discount rate?

It is our proposal that the annual revision of the discount rate follows a pre-established formula averaging the real yields on ILGS over the preceding 12 months. The new rate would then simply need to be published/announced by the Government Actuaries. A prescribed formula would remove the danger of subjectivity and personal views of the individuals otherwise chosen to set the discount rate, some of whom may be subject to pressures from different lobbying groups.

A broader review should be conducted by a panel of independent experts. The Government Actuary, acting on the advice of an expert panel, in order to set the differential rate for earnings heads of loss and, if necessary, report to the States of Jersey on any issues that warrant a change to the methodology concerning the discount rate.

We consider that the use of the Ontario model, splitting years and applying arbitrary rates to these periods should be avoided.

If the proposed assumed rate of return on a "low risk" portfolio is taken into account when setting the discount rate and a higher discount rate consequently applied, Claimants will be forced to take risk to overcome these issues. It is also unclear how you calculate the net return on alternative assets without basing data on past performance or simulated past performance which is neither reliable nor compliant with the FCA COBs 4.6.7 - 4.6.9.

We invite the States of Jersey to follow the decisions of the Privy Council in Helmot v Simon, the Bermuda Court of Appeal in Colonial Insurance Company Limited v Thomson and the PPO cases of Thompstone v Tameside and Sarwar v Ali & the MIB. This would allow a differential discount rate for earnings-related heads of loss, notably future losses for care and case management and loss of earnings, to reflect the real and very longstanding differential between pay and earnings inflation which has been variously put in the range of 1.5 - 2%.

We acknowledge that the Draft Law proposes the introduction of 0% floor to the discount rate. While we are not strongly opposed to this, we would like to see this implemented only in relation to price based heads of loss, with the courts being granted discretion to make further adjustments as is necessary, e.g. for cases involving earnings heads of loss, foreign nationals and other such differentials. Implicitly, this would mean departing from the aim of full compensation, which we contend the States of Jersey should not do absent the clearest of evidence and compelling policy reasons.

If notwithstanding all of our submissions the States of Jersey remains minded to pass legislation as contemplated by the Draft Law, it is essential that the rate does not depart from the full compensation principle and does not result in a significant proportion of Claimants going under compensated with the result that their damages run out during their life time. The consequence of this is Claimants would be unable to meet their injury related needs and fall back on the state for support. If this approach is to be taken then we invite the States of Jersey to apply the appended methodology when determining the discount rate(s) to be set. You will see that, using the GAD's highest return on RPI+1%, the result would, on our analysis be, a discount rate of -2.75% for prices related heads of loss and of -4.5% for earnings related heads of loss. If the 0% floor is to be implemented, that would obviously override and so the before mentioned rates would not be considered. However, what this does illustrate is the implausibility of setting a positive discount rate while succeeding in upholding the long established 100% compensation principle.

Julian Chamberlayne

In the event of any queries, please contact Julian Chamberlayne via email at jchamberlayne@stewartslaw.com

Stewarts Law

Stewarts Law

Solicitors

5 New Street Square

London

EC4A 3BF

For the attention of Julian Chamberlayne

23rd October 2018

Your ref: Our ref: IGG

Dear Julian

MoJ call for evidence: summary of responses by FOCIS member firms

Thus far, you have received responses from seven firms providing professional deputyship/trustee services to clients with personal injury awards. The responses provide information about the cost of investment, including financial advice, investment management, transaction costs, custodianship and collective fund management costs.

The evidence shows a clear and unsurprising inverse relationship between investment costs and the amount of capital invested. In other words, as a percentage of the capital invested, investment costs decline as the amount of capital invested rises.

Five of the firms provided anonymised data about 98 individual clients, with a total reported value of a little under £120 million. One firm provided aggregate data for 31 clients, with a total value of £30 million, and aggregate data for a further 100 portfolios but without quantifying their value. Therefore, there is data for 129 clients with a total value of around £150 million. The average portfolio in the sample is £1.16m.

The first observation to be made is that, on average, these portfolios are significantly larger than those modelled by GAD for the MoJ. For the latter, GAD was instructed to model portfolios to provide for a loss of £10,000 per annum for 30 years (therefore £300,000 +/- depending on the discount rate applied). Averaging the cost data provided in the sample is therefore bound to understate the real-world cost for such an assumed claimant, and this is an important caveat to the comments overleaf.

Respondents indicated that:

• Annual fees for independent financial advice to manage cash flows and overall risk parameters were largely in the range 0.25% to 0.75% of the capital invested, with the majority in the middle of that range, i.e. around 0.50%. These fees are exempt from VAT.

• Some respondents use individual discretionary fund managers to construct a tailored portfolio, with or without an IFA. Their reported fees range from 0.85% to 1.0% plus VAT (1.02% to 1.20% including VAT). Additional costs with discretionary fund managers include: custody fees, internal (in-house) fund costs, market transaction, brokerage and third - party costs. Some of these are paid per transaction and some as a percentage of value. The data is very noisy' and no meaningful average can be calculated for these additional costs, although some allowance for them is necessary. IFA fees are additional, as above.

• Alternatively, respondents use collective investment fund managers with advice from an IFA. Fund management fees range from 0.5% to 1.5%. Additional costs with investment funds include custodianship, audit, accountancy and fund administration. The overall cost figure for collective investments tends to fall in the range 1.0% to 1.5%. No VAT is charged on these costs or fees. IFA fees are additional, as above.

• Platform fees are reported in the range 0.1% to 0.3% depending on the value of the portfolio. No VAT is charged on these fees.

• There are outliers above and below the ranges referred to, as would be expected in such a small sample size and with a diverse population of clients.

The broad indication is that overall costs, including advice, tend to fall in the range 1.5% to 2%. I should point out that the costs set out above are incurred by claimants in managing cash flows and risk, selecting what to buy and what to avoid, when to sell, holding and keeping track of investments, the income they generate, capital gains and capital losses, and all regulatory compliance. They are not performance fees, i.e. payments to an investment manager in the expectation of achieving superior returns compared to a benchmark, so that the investor ends up better off than without active investment management. This is often what conventional' investors are seeking, although on average they are unlikely to achieve it. This is a crucial distinction when considering the real world that claimants have to inhabit when exposed to investment risk.

Yours sincerely

Ian Gunn Consultant

2

Adjustments for consideration in setting the discount rate

Step 1: Estimated annual investment rate of return1 1.00%

Adjustment to account for possiblity that 10% of claimants

Step 2: will be under compensated2 -1.50% Step 3: Adjustment for investment management fees and tax3 -1.75%

Adjustment to account for differences between UKRPI and

Step 4:

JRPI -0.50% Discount Rate for price related heads of loss -2.75% Step 5: Adjustment for earnings inflation[1] -1.75% Discount rate for earnings related heads of loss -4.50%

*Please note that even making the above assumptions claimants are still exposed to other risks including: risk that inflation may actually be higher (as only a very limited proportion of the model low risk Portfolios are inflation linked assets); the longevity risk that they may outlive their life expectancy; risk that their needs worsen; the risk that RPI is not representative due the nature of goods required for their specialist needs; and currency risk.

1RPI+1%, chosen as it is the highest return analysed in the GAD report 2017. 2from figure 1 (page 3) of the GAD report 2017. From that graph, this is the

discount rate that would result in roughly 10% under compensation risk with reference to Portfolio A. Therefore adjustment is the difference between +1% (our assumed nvestment return) and -0.5% (the discount rate that ensures only 10% undercompensation risk) = +1.5%

3Based on our initial analysis conducted with PFP (please find appended). Taken the midpoint between 1.5% - 2%.

The Discount Rate

A report for the Ministry of Justice

Prepared by

Paul Cox,

Richard Cropper, Ian Gunn &

John Pollock

7 October 2015

This report has been prepared within the context of guidance provided by the Ministry of Justice on the parameters within which the advice has to be provided. The authors can provide more extensive comment and advice if this is considered helpful.

The content of this report is the considered opinion of the authors but, for the avoidance of doubt, does not necessarily represent the opinion of any professional bodies or working parties where the authors are fellows, members or participants. In particular any input made to this report by Dr Pollock cannot be assumed to be necessarily reflective of the opinions of the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries or the Ogden Working Party.

AUTHORS

Dr Paul Cox is Senior Lecturer of Finance at Birmingham Business School, University of Birmingham and an Investment adviser at The National Employment Savings Trust (NEST). Since 2007 he has provided pension and investment expertise to the Department of Work and Pensions, the Personal Accounts Delivery Authority, and the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills. Paul has been involved in drafting several government consultations on pensions and investments and recently authored reports include Helping consumers and providers manage DC wealth in retirement' (2015) and Metrics and models used to assess company and investment performance' (2014). Prior to academia Paul was a fund manager at Kleinwort Benson and RCM Global Investors. He has been a representative on many regulatory and institutional investment working groups. He's currently a chief examiner of higher level practitioner examinations at a large chartered professional body.

Richard Cropper and Ian Gunn are consultants at Personal Financial Planning Limited, a company of Independent Financial Advisers dedicated to advising recipients of personal injury damages. Richard and Ian provide post-settlement advice on investment planning and management of personal injury damages, personal injury trusts, State Benefits entitlement, statutory provision of care and assistance, taxation and assurance. In addition, they both provide pre-settlement expert opinion on form of an award' issues (periodical payments or lump sum). Richard provided expert financial advice for the claimants in all four of the Thompstone et al indexation of periodical payments' cases, which have been pivotal in changing the damages landscape in favour of periodical payments in maximum severity.

Dr John Pollock is a Consulting Actuary. He has a background in institutional investment management and within the University sector but has specialised for the last 20 years in providing expert evidence in the UK Courts on a range of matters where actuarial input is required. He has been the representative of the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries on the Ogden Working Party' since the publication of the 4th edition of the Actuarial Tables with explanatory notes for use in Personal Injury and Fatal Accident Cases (the Ogden Tables') in 2000. He was recently involved in drafting the Actuarial Professional Standard X3 : The Actuary as an Expert in Legal Proceedings.

- The current legal framework and a reworking of the past approach in current economic circumstances.

- A review of actuarial practice in setting discount rates more generally.

- What is the appropriate measure of inflation?

- A financial economics approach to the discount rate.

- Should discount rates vary by duration of loss?

- Summary and recommendations.

Appendices

- Sources of data and evidence used.

- A financial economics approach to the discount rate – an expanded discussion.

- Trigger for review.

Set out below is a list of the issues the panel of experts has been asked to consider, cross- referenced to the relevant section(s) of our report.

Requirement | Chapter(s) |

The types of investment suitable for a personal injury claimant of the type envisaged by the law relating to the setting of the discount rate who is in receipt of an award of damages for future loss caused by personal injury | 1,2,3,4 |

The risks attached to investments | 2,3,4, Appendix 2 |

If more than one type of investment is considered suitable, the balance or mix of these investments that should be made by the claimant | 4, Appendix 2 |

The rate of return that each of these types of investment could reasonably be expected to produce, what assumptions apply to these rates of return (including assumptions about the economic cycle and economic outlook), and how those rates of return are calculated | 4, Appendix 2 |

Whether, and if so to what extent, these results depend on the amount of the lump sum to be invested, or on the period for which the investment is expected to be needed | 5 |

Whether more than one rate should be set | 5 |

What specific data and evidence sources were used to calculate the proposed discount rate, and why these are the right sources compared to other alternatives | 1, Appendix 1, Appendix 2 |

The specific methodology applied to calculate the proposed discount rate, including any assumptions about inflation, tax and investment management and administration expenses | 1,2,3,4, Appendix 2 |

For how long a period the rate of return proposed would be expected to remain an accurate indication of the rate of return to be taken into account under section 1 of the Damages Act 1996 and whether (and if so how) the length of that period could be affected by setting a different rate | Appendix 3 |

The balance between simplicity of administration of a rate and the accuracy of the rate | 6 |

The current legal framework and a reworking of the past approach in current economic circumstances

- The function of this report is to assist the Lord Chancellor, and his counterparts in the devolved administrations, in their review of the responses to the first of the two consultation papers issued by the Ministry of Justice in 2012 and 2013. The first was entitled Damages Act 1996: The Discount Rate and how should it be set. 1 The second was entitled Damages Act 1996: The Discount Rate - Review of the Legal Framework. 2

- The review of these consultation responses, this report and other investigations that are deemed necessary, will assist the Lord Chancellor, and his counterparts in the devolved administrations, in their decision making about at what level the discount rate (or rates) should now be set, how the rate (or rates) should be calculated and what circumstances should trigger future reviews.

- The Ministry of Justice has provided us with copies of the responses to the first consultation paper. Our brief review of these responses is summarised in Appendix 1 to this Report.

In England and Wales the Lord Chancellor has the power to prescribe the discount rate to be used in cases of personal injury and fatal accidents under Section 1 of the Damages Act 1996. More than one discount rate can be set and the Courts retain

In England and Wales the Lord Chancellor has the power to prescribe the discount rate to be used in cases of personal injury and fatal accidents under Section 1 of the Damages Act 1996. More than one discount rate can be set and the Courts retain

1 Ministry of Justice. (2012). Damages Act 1996: The Discount Rate. Available:

https://consult.justice.gov.uk/digital-communications/discount-

rate/supporting_documents/discountratedamagesact1996consultation.pdf. Last accessed 19th May 2015. 2 Ministry of Justice. (2013). Damages Act 1996: The Discount Rate. Available:

https://consult.justice.gov.uk/digital-communications/damages-act-1996-the-discount-rate-review-of-

the/supporting_documents/damagesact1996discountrateconsultation.pdf. Last accessed 19th May 2015.

[1]flexibility to diverge from the prescribed rate should they be persuaded that the circumstances of the case merit such a departure.

- Our instructions are that the report content is to be framed with the context of the first consultation exercise. This is the approach to the setting of the discount rate within the prevailing legal framework. We cannot comment with authority on the legal issues involved but summarise for completeness and ease of reference our lay understanding of these main principles below.

- We are grateful for the guidance provided to us by the Ministry of Justice who have in turn sought advice from Counsel.

- The decision in 1998 by the House of Lords in the conjoined cases of Page -v- Sheerness Steel, Wells -v- Wells and Thomas -v- Brighton Health Care Authority 3 detail the background to the current legal framework adopted by the Courts in the UK. The decision of their Lordships was followed in principle by the Lord Chancellor in 2001 when he exercised his power under Section 1 of the Damages Act 1996 and set the discount rate at 2.5%. There has been no variation in the rate since this time. The Lord Chancellor had the power to set more than one rate, but declined to do so. The legal issues considered in Wells have been revisited in a more contemporary financial environment in the Judgment of Sumption JA in the case Helmot -v- Simon heard in the Guernsey Appeal Court, and the subsequent appeal of the decision in this case to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. [2] 5 The principal investment related issues which arose from consideration of these various cases can be summarised as follows.

• The purpose of assessing the amount of a lump sum award as compensation for future financial losses is to place the claimant into, as far as is possible, the same financial position as if he had not been injured. In Wells, Lord Steyn referred to the "100% principle", i.e. that the victim is entitled to be compensated as nearly as possible for all future losses.

• The availability of Index-Linked Government Stock (ILGS) enabled the Court to consider a theoretical framework within which a claimant could invest in a portfolio of ILGS which, if held to redemption in an adequately structured portfolio, would provide for the future losses or costs as they fell due, without risk of erosion through inflation (to the extent the loss in future would have moved from current levels in line with the RPI, the basis of indexation of ILGS), or loss of capital. The availability of ILGS then provided the most accurate way of assessing the value of future losses in real terms (at least relative to RPI inflation).

• The claimant is not an "ordinary investor" in the sense of being able to wait for long-term returns to materialise, or to ride-out volatility in asset prices.

• The claimant may choose to invest in other securities offering the promise of higher rates of return but this is not relevant to the calculation of lump sum damages. Consideration of what is actually done with an award, how it is spent or how it is invested is not to be taken into account.

• A notional annuity' approach is envisaged with income from the lump sum award being drawn annually with an additional on-going diminution of capital, this being exhausted over the expected period of loss (itself a function of life expectancy).

• Simplicity of calculation of the discount rate and relative infrequent adjustment to the rate was seen to be desirable.

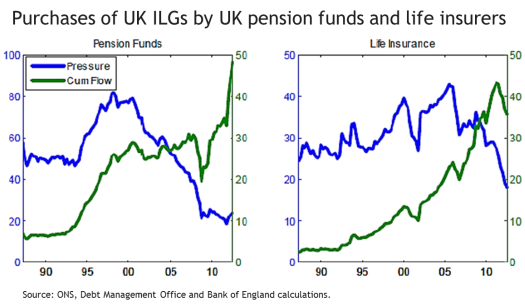

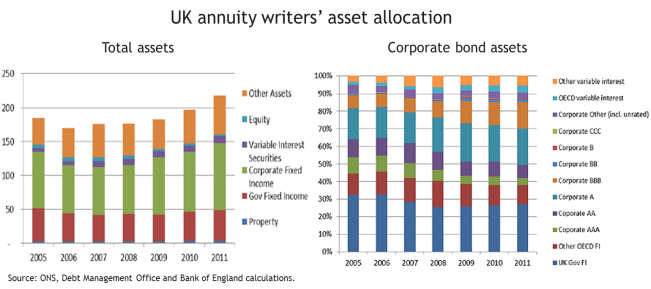

• An investment in equities was deemed inherently risky. Expenses to meet a future loss for a claimant could not be deferred until financial markets recovered (if they had fallen). Lord Hope noted in Wells that there could be no question about the availability of the money when the investor requires repayment of capital and there being no question of loss due to inflation'. It was noted in Wells that insurers and pension funds invest in ILGS to meet index-linked liabilities. Such action was deemed prudent'.

- Our subsequent review of investment alternatives to ILGS in Chapter 4 is framed with these clearly stated constraints in mind. This is the basis of our instructions.

- Our additional instructions are that neither general improvements in living standards nor qualitative improvements in an element of the claimant's loss over time are relevant to the Lord Chancellor's task of setting the discount rate. We are therefore instructed not to take these matters into account. The consequences of this constraint on our advice and opinions is considered in Chapter 3 where measures of inflation are reviewed.

- Given the requirement for this review of investment alternatives to be made within the current legal framework it seems appropriate to review how the Lord Chancellor set the rate in 2001 and to consider what discount rate (or rates) would now result from a comparable analysis being undertaken at the present time.

- In Wells -v- Wells their Lordships considered average gross ILGS yields over one and three year periods and made a pragmatic reduction for taxation, as a claimant investor bears taxation on income payable from ILGS. At the time the Judgment was made the average net annual ILGS yield (in excess of inflation) was around 3% and the conjoined cases were decided based on multipliers calculated at this rate. What this implied in practice was that if the award of damages was calculated using a 3% discount rate, and the claimant then invested in ILGS securing such a rate of return (if he desired to do so), then the "100% principle" would have been met.

The Lord Chancellor sourced ILGS yields from the Bank of England Debt Management Office for the three-year period to June 2001. The rationale behind Lord Irvine's decision is reproduced in Appendix A.1 of the first consultation paper referenced above. Additional insight is gained from the comments of Baroness Scotland in the House of Lords debate on the matter on 29th November 2001. In brief terms, Lord Irvine used a three-year average of those ILGS yields with over five years to maturity. The resultant figure was 2.46%.6 A 15% reduction for tax was deemed appropriate giving a yield of 2.46% – 0.37% = 2.09%. The discount rate was then set at 2.5%. What can be seen is that the Lord Chancellor followed the precedent set in Wells and set the rate with reference to ILGS, but it is known that he additionally considered returns on other securities to be relevant, together with the interests of claimants and those of defendants more generally. The authors presume this further review, beyond the largely arithmetic exercise of calculating and then referring to average net ILGS yields, was reflected in the rounding upwards' decision that was made in 2001. The authors note that only the interests of claimants are deemed

The Lord Chancellor sourced ILGS yields from the Bank of England Debt Management Office for the three-year period to June 2001. The rationale behind Lord Irvine's decision is reproduced in Appendix A.1 of the first consultation paper referenced above. Additional insight is gained from the comments of Baroness Scotland in the House of Lords debate on the matter on 29th November 2001. In brief terms, Lord Irvine used a three-year average of those ILGS yields with over five years to maturity. The resultant figure was 2.46%.6 A 15% reduction for tax was deemed appropriate giving a yield of 2.46% – 0.37% = 2.09%. The discount rate was then set at 2.5%. What can be seen is that the Lord Chancellor followed the precedent set in Wells and set the rate with reference to ILGS, but it is known that he additionally considered returns on other securities to be relevant, together with the interests of claimants and those of defendants more generally. The authors presume this further review, beyond the largely arithmetic exercise of calculating and then referring to average net ILGS yields, was reflected in the rounding upwards' decision that was made in 2001. The authors note that only the interests of claimants are deemed

6 Although in a document entitled "Damages Act 1996: Briefing Note on Index-Linked Gilt Average Yield Calculation (Data Issues)", dated 6th July 2001, written by the UK Debt Management Office (DMO), obtained by PFP under a Freedom of Information Request, the DMO confirms that their calculation of the yield on all index-linked gilts for the three years up to and including 8th June 2001 was 2.61%. This was said to be based on the following assumptions:

• All IGs were used in the calculation, with no adjustment for the near maturity portions of IGs close to redemption, the rump stock, or WI stock;

• Daily data yield observations;

• Simple average;

• The use of the standard market convention of a 3% inflation assumption in the calculation of real yields from prices.

This figure was then adjusted to 2.50% for various technical reasons and corrections.

[1]relevant in Wells, the impact of any decision about the discount rate on defendants was not deemed relevant.

- The Courts have the power to use a different discount rate, or rates, if they can be persuaded that the features of the case justify a departure from the rate set by the Lord Chancellor. The authors are aware of a number of cases involving non-resident claimants 7 and are also familiar with the reported decisions in a number of cases considering changes in economic circumstances more generally 8 and where periodical payments are not available. 9 The Courts have not yet used a rate other than 2.5% in circumstances where the Damages Act 1996 applies, although they have in jurisdictions where the Act does not apply and when assessing future losses in cases not necessarily involving injured persons. [2]

- Before reworking the analysis made in 2001 in the context of current economic circumstances it may be helpful to detail some of the basic features of ILGS.

• ILGS offer coupon payments and redemption proceeds that are linked to the Retail Price s Index (RPI). There has been some debate over whether Consumer Price s Index (CPI) linked ILGS should be issued in future but none have been issued to date.

• The substantially greater part of the return from ILGS comes from the return of indexed capital. In recent years stocks have been issued with trivially small coupons (as low as £1/8 p.a. per £100 nominal). A claimant investor would be taxed on income but not on gains in capital.

• The ILGS market is both substantial and liquid. There are securities with redemption dates ranging from 2016 to 2068. The crude average future term is c21 years.

• There are two types of security, those with an eight-month lag in indexation and those with a three-month lag. For practical purposes this can be ignored. The actual level of future inflation is essentially irrelevant; ILGS protect again inflation as measured by the RPI.

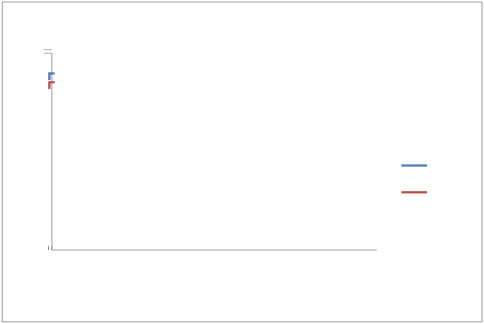

- The graph below shows the three-year moving average of yields on ILGS securities with over five years to maturity (as were considered by the Lord Chancellor in 2001). [3] Figures are publicly available for 0% and 5% inflation assumptions (only relevant for the lag') and the 0% figures have been used below. The differences are not material, as noted above.

Gross over 5 year ILGS yields - 1 and 3 year averages

Gross over 5 year ILGS yields - 1 and 3 year averages

3.00

2.50

2.00

1.50

1.00

1 year 0.50

3 year 0.00

-0.50

-1.00

- Current and historic average real yields are noted in the table below.

Term | Current Yield | 1-Year Average Yield | 3-Year Average Yield |

0 to 5 years | -0.73% | -1.02% | -1.31% |

Over 5 years | -0.84% | -0.73% | -0.30% |

All stocks | -0.83% | -0.74% | -0.32% |

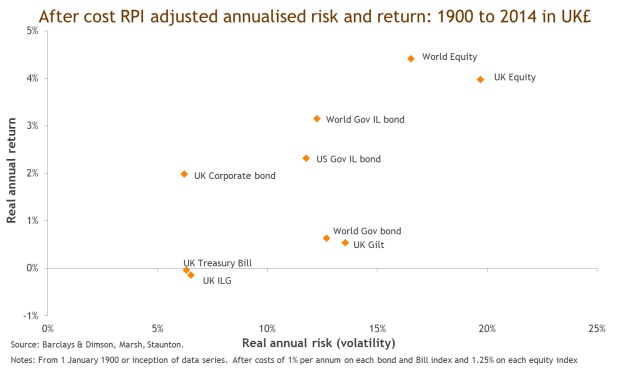

- The graph shows quite clearly that there has been a marked decline in ILGS yields since 2001, when the current 2.5% discount rate was set. This is an investment phenomenon that has not been confined to the UK. In the US real yields on Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPS) currently average 0.7% [4] and in the Eurozone real yields on inflation-protected securities are 0.1%. [5] The lower ILGS yields in the UK relative to yields available on inflation protected securities in the US and Europe may be explained, at least in part, by the basis of indexation, being the RPI in the UK and CPI measures in other countries. Inflation measures are discussed in more detail in Chapter 3.

- This is to be expected. Real yields will be higher when economies are experiencing growth in real terms and demand for credit is high, and will be low in periods of weak economic growth when consumers and businesses focus on saving, not consumption. The pace of the decline in ILGS yields accelerated after the financial crash in 2008. Those wishing to invest conservatively have had to accept lower rates than in the past.

A Report by the International Monetary Fund contains a useful summary of trends in

this regard. [6]

- Although opinions can differ on the matter, from an economic perspective one might expect the real yields on ILGS to reflect investor opinions on likely real economic growth in the UK (or real yields in other countries to reflect likely real economic growth in those countries). Government debt has to be financed and repaid from taxation revenue, which is a function of economic activity.

- Anticipated levels of real economic growth have implications for anticipated levels of earnings growth relative to inflation. One would expect real earnings growth to be high when real economic growth is high (which in turn would most likely be associated with higher levels of real yields on ILGS) and real earnings growth to be low when real economic growth is low (which in turn would be most likely associated with lower levels of real yields on ILGS).

- The issue of the appropriate levels of inflation to consider in this exercise is discussed in Chapter 3. In this discussion we are mindful that our instructions are that neither general improvements in living standards nor qualitative improvements in an element of the claimant's loss over time are relevant to the Lord Chancellor's task of setting the discount rate. The discount rate is, put simply, the return after tax and management expenses relative to inflation', whatever that might be considered to be.

- A further consideration mentioned by their Lordships in Wells was the fact that a lump sum award based on a discount rate calculated with reference to ILGS would most closely match the outcome for a claimant in respect of a Periodical Payment Order (PPO). At the time of Wells these could only be arranged by consent (this situation still prevails in Scotland, Guernsey, Jersey and the Isle of Man) but since the Courts Act 2003 the number of PPOs established, primarily for care costs, has grown significantly. If there is to be consistency between those cases settled by means of a PPO and those cases settled by means of a lump sum, then the purchase of a portfolio of ILGS might be considered to most closely replicate the expected PPO cash flows (setting aside for the moment the issue of the measure of PPO indexation, which now conventionally departs from RPI).

- If the current Lord Chancellor were to replicate the analysis made by his predecessor in 2001, then:

• The starting point would be the historic average of over five year ILGS yields.

• This is -0.30% over a 3 year period or -0.73% over a 1 year period.

• A modification then needs to be made for tax on the (indexed) coupon payments. The tax burden will vary from claimant to claimant, and their Lordships in Wells and, subsequently the Lord Chancellor, took a broad brush approach to solving this problem by simply reducing the prevailing gross real yield by 15%, suggesting a reduction to the gross yield at the time of 0.37%. The change in yields since 2001 and steady issuance of more securities with lower coupons complicates matters. The deduction for taxation will be modest. Time constraints have not allowed us to consider the issue of taxation in detail and for practical purposes we would suggest that this issue can be addressed in the rounding aspects of the calculation.

- The calculations outlined above suggest that the discount rate in current circumstances, if set using exactly the same methods used by the Lord Chancellor in 2001, would be between -1% and -0.5% depending on the allowance for taxation and the averaging period being used. From an actuarial perspective, the one-year average is considered to be more appropriate, and the panel is in agreement that rounding should be to the nearest half-percentage rate for use in the current Ogden Tables. On this basis, the discount rate would be -1%.

- A practical consideration which merits comment is that the ILGS market extends at the current time to 2068, a period of 53 further years. At the time of the decision in Wells the ILGS market extended for 31 years to 2030 [7]. This period of 53 years exceeds the life expectancy of many claimants (those in their early to mid-thirties in normal health) but is less than the life expectancy of some young claimants (if they have average life expectancy, although many do not). Life expectancy at birth is now around 90 years and this is an effective upper bound on the duration of losses likely to be considered by the UK Courts. The concept of discount rates trending towards an ultimate forward rate' features in insurance applications as will be discussed in the following chapter. Currently, nominal discount rates used for terms beyond those available in the conventional gilt market are somewhat higher than those at the longest available terms. This might suggest use of a modestly higher discount rate to apply to cash flows in the very longest tail of the spectrum being valued. The issue of different discount rates for different terms of loss is discussed in Chapter 5.

- A focus on ILGS returns can however hide more subtle features of the problems under consideration. If an award of damages is calculated at, say -0.5%, and a claimant invests in ILGS of approximate terms securing a net yield of -0.5%, then he would be fully compensated, but only to the extent that the heads of claim being valued will increase in future in line with the RPI. Chapter 3 will discuss whether claimant inflation is indeed properly estimated by the RPI or if alternative measures are more appropriate. These would impact on the discount rate assessed solely by an inspection of ILGS yields. Put crudely, if a head of claim was expected to grow faster than RPI in future then use of an ILGS based discount rate would overstate the discount rate, leading to under-compensation, and vice versa. To the extent that low real interest rates may be predictive of weak economic growth, and hence earnings growth, this issue may be of less importance than at times in the past when real interest rates were higher.

A review of actuarial practice in setting discount rates more generally

- The assessment of the present value of future earnings, care costs, services or pension rights is fundamentally an actuarial exercise. The Courts now accept this and the Actuarial Tables with explanatory notes for use in cases of personal injury or fatal accidents (known as the Ogden Tables') [1] are widely used by the Courts in the UK when making future loss calculations. In England and Wales they are admissible in evidence by virtue of Section 10 of the Civil Evidence Act 1995 and they are universally applied in other legal jurisdictions in the UK. This was not always the case. [2]

- The essentially actuarial aspects of the matter are, firstly, that the expected duration of

the payments being valued is a function of the projected mortality experience of the claimant (which varies by both age and gender) and, secondly, that the future payments require to be discounted' for accelerated receipt. The future payments are generally predictable' in real, inflation adjusted, terms and the discount rate is chosen accordingly. This means the Courts can conveniently make their calculations in current money' terms, the impact of inflation' being disregarded. Comparable calculations are made by actuaries in a large range of commercial applications, pricing insurance contracts, valuing pension liabilities and in all reserving and solvency assessment exercises. From the defendants' perspective the sum of money paid by them to a claimant (unless settled by a PPO) is a transaction which

extinguishes the liability they have incurred for restitution of the damages under consideration. By contrast, from the claimants' perspective the sum of money awarded represents a reserve to provide for the future cash flows as they fall due, anticipated to be exhausted over the period of assumed loss.

- The basic process followed when assessing the present value of any set of future cash flows is to determine the amount and timing of the future payments and then to discount these to a current time, having assigned to each future cash flow an estimate of the probability that it will be paid. As an example, consider a multiplier selected from the Ogden Tables. The future cash flows being valued are £1 p.a. and the probability that each future annual cash flow will be paid is the probability that the claimant will have survived to this future time of anticipated receipt. The multiplier is then the sum of the discounted expected' future cash flows. The impact of the discount rate is crucial. At a 2.5% discount rate for a term certain of 50 years, the value of a payment of £1 p.a. is £28.72 (see Table 28 of the Ogden Tables). Of this total around 1% is contained in the value of the 50th payment (see Table 27 of the Ogden Tables). At a -1% discount rate the value of a payment of £1 p.a. is £64.96 and of this total 2.5% is contained in the value of the 50th payment. Not only does the discount rate influence the size of the award but lower discount rates necessitate more accurate estimates being made of the future survival probabilities.