The official version of this document can be found via the PDF button.

The below content has been automatically generated from the original PDF and some formatting may have been lost, therefore it should not be relied upon to extract citations or propose amendments.

Jersey Landlords Association Tuesday 26 November 2019

Public Health & Safety (Rented Dwellings) (Licensing) (Jersey) Regulations

OPPOSING PAPER

from the Jersey Landlords Association [the "JLA"]

to the Environment, Housing & infrastructure Scrutiny Panel [the "Panel"] PREAMBLE & LACK OF CONSULTATION

1 The Draft Rented Dwellings Licensing Regulations (P106/2019) is due to be debated in the

States Chamber on 21 January 2020, following its consideration by the Panel.

2 Regarding any Orders or Regulations to be drafted in accordance with the Public Health

and Safety (Rented Dwellings) (Jersey) Law 2018 [the "HSRD Law"], certain undertakings were given, orally, in the States Chamber by Ministers, including the present Minister for the Environment. For examples, see Hansard, 25 Sep 2018, item 5.1; and 7 June 2018, item 10.1.11). These undertakings were essentially that full Consultations would take place with all key stakeholders (including the JLA in particular) before any such Orders or Regulations were put before the Assembly for approval. This did not happen, either before the "Standards & Hazards" Order was made on 1 December 2018 or before the Licensing and Inspection Regulations (p106/2019) were lodged Au Greffe on 1 October 2019.

3 The Panel's own website carries a helpful summary of this present review. However, it

includes an assertion that consultation took place this last summer (2019), in respect of the currently proposed regulations. So far as the JLA is concerned, this assertion is incorrect.

The Environment Minister's 11-page Report, leading into P106/2019, makes no mention of there having been any such consultation this last summer and reports no views received either from landlords or from tenants or from agents. On the other hand, he does make assertion after assertion of "facts", which are simply not in evidence and his report provides little, if anything, in support of its assertions of "fact", other than minimal anecdotal (but completely non-specific and uncorroborated) evidence. For example, the following "factual" observation appears prominently at paragraph one of his Report:

"The Department responsible for enforcement continues to uncover rented dwellings in really poor condition, some in the control of allegedly good' landlords. It is certain that there are many more that the regulators simply have no knowledge of."

So, we ask:

o Which Department is responsible for enforcement exactly?

o How many poor condition dwellings have they continued to uncover?

o And in what time-frame have they been uncovered?

o What is the definition of "really poor"?

o Exactly how many is "some"?

o What is an "allegedly good' landlord"?

o Is this an implication that there are, in fact, none?

o How certain is "certain"?

o How many is "many more"?

o Who are the regulators, exactly; and what are their qualifications to regulate?

o And, if the regulators have "no knowledge" of a fact asserted in the quote, how can the Minister be so "certain" of that fact's actual integrity?

It is difficult to accept that those who read this short anecdotal quote are intended to rely upon it as meaningful evidence. Yet it is a premier point (if not the premier point) set out in the Minister's case. By way of support for this view, the JEP has selected it for repetition in an article at the top of page 5 in its edition, dated Monday 25 November 2019 (see PDF attachment). It is effectively the JEP's summary of this 11-page ministerial report, for public consumption.

4 So far as government consultations are normally defined; they would usually involve a

frank, face-to-face, exchange of views between the government and key stakeholders, at least some of which views would colour and/or generate amendments to the thinking of the opposing team. Despite the promises made and undertakings given, no such consultations have ever taken place with our Association on these presently proposed Regulations. Nor, so far as we know, have there been any "true" public consultations on these proposed Regulations, either with private landlords or with tenants or with taxpayers and nothing has been published to demonstrate otherwise.

Last Summer, there was merely a lecture (with PowerPoint presentation) given on 11 June 2019, by the outgoing director of the Environmental Health Department (Mr Petrie). His presentation set out the Department's proposals for new Regulations. There were three or four repeats of the lecture that day and the JLA had one or more attendees at each of them. The JLA's request to be allowed to express our views to the audience was promised at first but was eventually denied. So we could only place our opposing literature on each audience member's seat with the hope they would read it.

However, out of several thousand private rental-sector landlords in Jersey, the total attendees that day barely reached into 3 figures (after deducting the Department's own staff attendees). This was primarily because very few people had been made aware of the event taking place at all. The JLA's written views (copies of which were handed to Mr Petrie and his staff that day) received no subsequent acknowledgment or response. They were effectively ignored and were certainly not published or circulated publicly after the lecture event day.

Yet, all the key stakeholders will incur material start up and annual costs, which have so far been given little publicity by the Environment Department, the Housing (ie Population) Department or the States Treasury.

5 Consequently, States Members remain mostly unaware of the many reasons why these

Regulations are unnecessary and why they would, in our view, be bad for Jersey's economy as a whole and should, therefore, be rejected by the Assembly.

6 P106/2019, if approved, will open a pit of red tape. This is despite almost all politicians,

who recently stood for election, having declared that they wished to see an overall reduction in the volumes of red tape, with which Islanders and Island businesses now have to cope.

7 In the circumstances, the JLA would welcome an opportunity for its representatives to

address the Panel on this issue, mainly in order to answer questions on this Paper. It would enable the Panel (and States Members generally) to be appraised of, and to understand, the opposing viewpoint of the Island's private rented-sector dwelling owners, who provide about a quarter of all dwelling accommodation in the Island and almost 60% of the rented dwelling accommodation in the Island.

8 We also seek to draw a bigger picture, illustrating how Jersey's housing needs (particularly

its urgent need for many more rental housing units) is a vital element of the Island's economy, which will be placed in jeopardy by the implementation of these unnecessary Regulations.

MISLEADING REPORT in P106/2019

9 Whilst the principles of the HSRD Law were indeed approved unanimously by the States

Assembly on 13 December 2017, what is not said in the Report to P106/2019 is that the approving vote was held in the complete absence of any details relating to any prospective Order or Regulations, subsequently to be associated with the said Law. The JLA objected strongly to that unparliamentary haste to approve a law, in relation to which no practical details had yet been made available and which was unlikely to come into effect for almost a year. Our concerns were ignored, save that, in the meantime, they were temporarily assuaged by assurances in the Assembly that serious consultations would take place before any such Orders or Regulations were drafted and made by the Minister at that time, Deputy Luce of St Martin.

10 The HSRD Law did not then come into effect until 1st October 2018 (10 months later), by

which date, no associated Order or Regulations had yet been made or published. That was despite the previous Minister for the Environment's assurance in the States on 13 December 2017 (when referring to the General Election scheduled for May 2018) that he would "move mountains to try to get those Regulations back to this Assembly before the elections" (See Hansard 13 Dec 2017, item 4.2.3).

11 At that time, thoughts of annual licensing and inspection of ALL rented dwellings in Jersey

were in their infancy and would not become public knowledge but the HSRD Law was passed anyway on the pretext that existing laws, relating to the physical condition of rented dwellings, gave the Environmental Health Department insufficient control over landlords to ensure the safety of tenants.

That was a matter of opinion as existing laws (and their amendments) had, in practice, provided tenants with adequate protection for over 80 years. The Report to P106/2019 mentions the 1934 Public Health Law (but not its much more recent amendments) and the 1999 Statutory Nuisances Law but fails to mention the very relevant 1977 Fire Precautions Law or the 2002 Planning and Building Law (or its multiple Building Bye-law amendments, all of which are cited in Article 21 of the HSRD Law as not intended to suffer from any derogation effect following the promulgation of the HSRD Law. There are probably others which are not specified individually but are covered by Article 21(e) which refers to "any other enactment relating to public health and safety".

States Members are reminded that many of the most poorly maintained dwellings in Jersey during the last 30 years (pre Andium Homes) were, in fact, those owned by the States of Jersey itself and rented out to locally-born people, in the form of "social housing".

12 The main reasons given in the proposition to justify the proposed new Regulations are:

- To provide Government with new data to establish the number, whereabouts, suitability and occupancy of all rented dwelling accommodation in the Island, so that it can be subjected to these proposed regulations and will permit Government to formulate future policy.

This information is already available to several arms of Government but it has just not been shared and collated adequately and/or published. Here are four examples of the availability of such data and there are probably others:

- Since the 2012 Control of Housing and Work Law came into force on 1 July 2013, it has been a requirement, under Article 9(3) thereof, that any person in control of a property must provide the Chief Minister (on the form downloadable from the Population Office website – see PDF copy attached) with the full details of any persons residing in that property for three months or more and, under Article42(1) thereof, the Chief Minister may provide statistical information to any other Minister for the purpose (inter alia) of "assisting in the development and evaluation of public policy". The ready availability of that information, if and when requested, could hardly be clearer.

- Under the Planning Law & the Building Control Bye-laws, appropriately detailed applications must be made by any property owner, wishing to change the use of his or her property. So a property that is to be rented out as dwelling accommodation, where such was not its use previously, must first be granted ministerial permission for that change of use. That application and any associated information is then made public on the website managed by or on behalf of the Planning and Environment Department and could be searched by anyone who wished to examine the published details about any particular property.

- Under the Parish Rates Law, property owners must file an annual declaration, which provides the Connétable and Rates Assessors with details of any change in the use and/or configuration of any property in their Parish and with the details of any adult who is eligible to vote in Jersey. This information and the rateable value of each property is entered into a publicly accessible Register, which would readily be made available to any person authorised to inspect it.

- Many property leases (ie contract leases) are recorded in the Royal Court of Jersey Registry and the Register is open for public inspection. This a fourth method of obtaining information on property in Jersey which has been rented out privately.

- To be able to inspect the quality and the ongoing maintenance state of rented dwelling property annually (so as to ensure minimum standards of health and safety are maintained), without first having to wait for a complaint to be received from a dissatisfied tenant.

This proposed licensing and inspection regime will be a costly and time-consuming process for ALL private-sector landlords and their tenants, despite there being only a very small number of delinquent landlords in Jersey. No real or recent evidence that there are many more than a few has been provided in support of the proposition; only anecdotal evidence has been presented in support.

More importantly, by the existing Regulations to the HSRD Law, which were already brought into effect in December 2018 by ministerial Order, Environmental Health officers are permitted to enter and inspect all rented dwelling properties and to order the owner of ANY sub-standard rented dwelling property to carry out appropriate remedial work to bring any such property up to basic minimum standards.

So, the only aspect of the proposed new Regulations that is truly additional to the HSRD Law and its existing Regulations is the proposed need to register and licence all rented dwelling properties (that are not already Registered Lodging Houses under the Lodging Houses Law) and the requirement for owners to pay a large annual licence fee in respect of each unit of rented dwelling accommodation, for the privilege of being Registered, Licensed and Inspected annually.

- To be able to withdraw the Licence for a sub-standard property (or any sub-standard part thereof) and to shut it down if deemed necessary.

Whilst shutting down a privately rented dwelling property, on the whim of an overly enthusiastic inspector, may punish a delinquent landlord, it will also punish the tenants by rendering them homeless. It will also reduce the availability of rented dwelling stock in the Island.

So, what process is being proposed for rehousing such tenants, quite possibly at very short notice? Those same tenants may, in fact, be perfectly satisfied with their present accommodation (even if the inspector is not happy) and may never have lodged any complaint about it in the first place; perhaps because the rent was cheap and they only intended living there for a few peak season months.

Fining a seriously delinquent landlord would be a much more practical solution than shutting down a property. This is because any landlord faced with a fine, will prefer to spend his money on repairing his property than paying the same money over to the Government.

To reinforce this point, the size of such fines should be realistically aligned with the likely cost of the remedial work required. It should be notified to an offending landlord in writing, together with a reasonable timetable within which the notified remedial work is to be carried out in order to avoid payment of that fine. Any such timetable should obviously take into account the availability (or scarcity) of professional tradespeople to do the work.

As further encouragement for landlords to do the right thing, fines levied (or a percentage thereof) could be rebated to an unduly slow landlord, once the required remedial work has been completed. In any event, the rent, of any such sub-standard property, should be allowed to rise to reflect a reasonable return on the cost of improvement works, once they have been completed.

- Children's life-chances and future well-being will benefit from an improvement in housing standards.

This reason is a worldwide given; but it reflects 13-year old research, which has already been taken into account by Government in Jersey and by the vast majority of the Island's landlords. Even so, tenants can only afford to pay, in rent, what they believe they can afford and cannot realistically expect to go through life, being "given" everything that they may not otherwise be able to afford.

- Registration without licensing does not work.

We disagree. The example cited in the Minister's Report is an irrelevant comparison, relating to research on a quite different local issue. Market forces should never be distorted in an effort to enforce a law which the market believes to be unreasonable and/or undesirable. Carrots are always preferred to whips.

- To ensure that rented dwelling properties are compliant with improved standards before they are permitted to be rented out.

This is pure duplication of other laws. The Ministers declared objective is exactly what the existing Building Bye-laws and Fire Service certification (to name but two) are intended to achieve. Excessive or duplicate legislation will increase costs when market forces should be allowed to determine the desirability or undesirability of all units of dwelling accommodation. Rents will best be moderated by encouraging investors to build more dwellings for rent and reduce scarcity. The present proposals will discourage investment and will increase scarcity and, consequently, rents.

Also, complaints from tenants or prospective tenants will generally bring material defects in a rented dwelling to the attention of the Environmental Health Department. In the meantime, the Department should concentrate more on publicising (in several languages) the difference between acceptably safe standards and unacceptably unsafe standards, so that tenants will know what they should and could properly complain about and they might also be able to learn what maintenance is the duty of tenants.

- To ensure that all recipients of rent are paying their due income tax on that revenue.

As this enforcement is not the duty of the Environmental Health Department, this objective has not yet been put in writing; but it has been spoken of in the background.

13 It is implied in the Minister's Report that these proposed Regulations will have no material

effect on Island manpower. This is patently untrue. There will, in fact, be a very significant effect. The Report section of the proposition (at the middle of page 4) actually says:

".. ensures that there are no additional resource implications through the approval of these Regulations.".

Not only will there be a significant increase in inspectorate personnel, in order to inspect (and police by revisiting) some 11,000 or more dwelling units but the relevant tradesmen, needed for professional testing and subsequent remedial works, are also in desperately short supply in Jersey. This tradesperson shortage results directly from insufficient Right-to-Work permits and immigration licences having been granted by our authorities where needed. Furthermore, any lack of supply and increased demand for professional tradesmen will inevitably result in their further increased charge-out rates; increased costs to landlords and consequently increased rents.

In suggesting that these proposed new Regulations will come fully into effect by mid-2020, it seems clear to us that the practical viability of this whole licensing and inspection project has simply not been thought through carefully enough.

14 As stated in the first paragraph of the Report section of the Minister's proposals, the

"principles" of the HSRD Law 2018 were approved unanimously by the States Assembly. However, the Panel is reminded that no Orders or Regulations had yet been drafted at that time and that the Minister promised full consultation on these essential matters before they were to be enshrined in Law. As already mentioned above, no such consultation has ever taken place. Perhaps that was why only "the principles" of the Law were approved by the Assembly in the first instance.

15 If these new Regulations are now approved by the States, despite being (in our view) wholly

unnecessary, they will then be pro-actively applied, retrospectively, to ALL 11,000 privately rented self-contained units of accommodation in Jersey. Primarily, the proposed new Regulations are unnecessary because the reasons given, in support of the proposition, have neither been substantiated with hard evidence nor do they otherwise offer any real merit.

16 It is apparently intended that the Registered Lodging Houses Law will shortly be repealed

too. This may well be a good repeal but one hopes that face-to-face consultation, on the detail and implications, will take place with the key stakeholders and the JLA, well before any repeal happens.

DOING THE MATHS

17 According to the March 2011 census, the Island population at that time was 97,857 and

there were some 41,600 occupied dwelling units. This gave an average occupancy rate of 2.35 persons per household, when adjusted to include 1,883 people reported as "living in communal establishments" (of which there were 157 such properties, including hospitals, care-homes, hotels, hostels, etc and the prison). This average occupancy rate per household had fallen over the previous 10 years by about 0.07 persons per household (ie from about 2.42 persons per household to 2.35 persons per household).

According to Jersey Government's Statistics Dept, our population at the end of 2018 had risen to 106,800. This represents an increase of 9.1% in just under 8 years; about 1.1% per year on average. So, the resident population today can reasonably be estimated at about 108,000 persons.

Dividing this 108,000 population by 2.30 persons per household (to allow for an ongoing small reduction in the average occupancy rate per household), suggests that there are now about 46,950 occupied dwelling units in Jersey (plus the aforementioned "communal establishments").

In the March 2011 census, there was a total of:

41,600 occupied dwellings, housing 97,857 persons and divided up as to:

Privately rented dwelling units:

being 32% of the total households (ie 13,300 homes, housing some 31,300 persons).

Publicly owned rental units (ie the States [now Andium], Parishes & Housing Trusts)

being 14% of the total households (ie 5,840 homes, housing some 13,700 persons).

Owner-occupied dwellings:

being 54% of the total households (ie 22,460 homes, housing some 52,857 persons).

Consequently, for the purposes of the projections set out in this paper, the following assumptions for late 2019 have been calculated and adopted by us: Totals: 47,000 occupied dwellings, housing 108,000 persons and divided up as to: Privately rented dwelling units: 11,000 homes, housing some 25,300 persons being 23.4% of the total households (rather than 32% as in 2011). Publicly owned rental units: 8,000 homes, housing some 18,400 persons being 17.0% of the total households (rather than 14% as in 2011). Owner-occupied dwellings: 28,000 homes, housing some 64,300 persons being 59.6% of the total households (rather than 54% as in 2011). |

18 Hopefully, one can be forgiven for wondering why the well-resourced Environment

Department (with the assistance and co-operation of other government departments) has been unable to produce the same (or similar) calculations as have been assessed by us for inclusion in this opposing Paper, in the two rectangular statistic boxes set out above.

In particular, this would have enabled States Members to take note of the 8% or so reduction, since 2011, in the investment by private landlords in Jersey's rented dwellings industry. That investment appears to have fallen from 32% to 23.4% of the total stock of dwellings in Jersey. Some 13,300 dwellings (housing 31,300 tenants) appears to have reduced to about 11,000 dwellings (housing about 25,300 tenants).

19 Continuing to do the licensing and inspection regime maths, we calculate that Jersey will

need at least 12 full-time Environmental Health inspectors to implement and police the annual inspection regime proposed under the new Regulations. This assertion is based conservatively on 11,000 privately rented dwelling units in Jersey, which is 2,300 less than the 13,300 in the 2011 census, when the resident population was 10,000 fewer than today.

Our assessed requirement of 12 inspectors assumes 940 inspections per inspector per year (ie 5 per day for 4 days per week for 47 weeks per year). This calculation allows one day per week for other business visits in the course of their duties; plus return follow-up visits after conducting inspections and finding defects requiring remedial work; plus completing all the relevant paperwork; not to mention possible court attendances in the event of prosecutions. Our calculation makes no allowance for sickness or pregnancy amongst the inspection staff or their partners. If inspectors could only achieve an average of 4 inspections per day instead of 5 per day, then 15 full-time inspectors would be needed instead of 12.

Any law which demands constant policing would quickly become toothless without that regular policing, so how can the Environment Minister realistically assert, in his proposition, that these regulations, if adopted, will have no manpower implications for the economy?

20 Based on the proposed licence-fee structure of about £150 (on average) per dwelling unit

per year, the total revenue from this "non-profit" scheme will be in the region of about £1.65 million per year. That suggests that each of the estimated 12 inspectors will earn about £138k per year. In the alternative, the Environmental Health Department will generate a profit of £1million or more per year. Perhaps it is reasonable to ask on what this windfall profit is likely to be spent; or will it just be acknowledged by Government as being just another a "stealth" tax?

21 Based on the figures calculated in the previous paragraph, the new Regulations will

obviously be inflationary, as have also been the Deposit Protection Scheme, the Health & Safety Regulations for registered rental homes and the Tenancy Law (2013) amongst others.

More recently it has been suggested by certain politicians that rent controls should be brought back into operation. Yet, recent reductions in the supply of privately rented accommodation (due to landlord concerns about excessive recent legislation and their consequent departure from the home-letting industry in Jersey) have already caused rents to increase, in the last two or three years, by 10% or so.

On the other hand, despite the various law changes imposed during the last decade, domestic rents have increased, during the last 30 years by an average of less than 4% per year, which has been roughly in line with inflation over the same period. In other words, market forces have prevailed without the need to re-impose Rent Controls.

ECONOMIC & LEGAL EFFECTS ON LANDLORDS & INVESTORS

22 We believe that the 8% or so reduction, in private sector rented dwellings, incorporated in

our projections (at paragraph 18 above), has been the result of investors now withdrawing from (or placing their funds elsewhere than in) Jersey's rented dwelling sector. In our submission, this has occurred (exactly as might readily have been predicted) following the significant legislative and other red tape pressures imposed on Jersey's privately rented residential sector since 2011.

This investment reduction is also coupled with a multiplicity of legislative threats, some of which are already current and some of which are understood still to be in the political melting pot. Included in this list (in no particular order) are:

o capping of rents and other market-eroding rent controls;

o banning restrictions on families with children, living in privately let accommodation;

o banning commissions payable to introduction agencies by prospective tenants;

o banning of non-resident investors from investing in Jersey's privately rented sector;

o overly stringent taxation on property rental income, whereby property expenses (such as repairs, improvements & loan interest) cannot be set off against taxable income;

o lack of help for landlords who suffer trashing of their property by uncaring tenants;

o imposition of minimum three-month notice periods for tenants who cannot pay a 3-month deposit but then default on the rent they agreed before taking up residence;

o continuation of the costly, inefficient and time-consuming deposit protection scheme;

o planning restrictions on creating small, self-contained, dwelling units suitable for relatively short-term immigrant workers;

o A political mindset which is reluctant to recognise & accept the long-established fact that many short-term immigrant workers prefer to pay a low rent during their working stay in Jersey rather than to occupy superior quality (or excessively spacious) accommodation. This lifestyle choice enables them to send home as much of their pay as possible, in order to maintain their home-based families to a materially better economic standard than would otherwise be possible.

23 Recently (on 3 October 2019), the JEP quoted Housing Minister, Senator Mezec, as saying:

"These new Regulations will only punish those who break the law."

This is simply not true in practice. The new Regulations will financially affect (and thus "punish") EVERY landlord of privately rented, self-contained accommodation. Whilst the proposed Licence Fees and other additional costs would, in the first instance, be payable by landlords, that extra annual expenditure will simply be passed on to tenants by way of increased rents and will thus "punish" them too. Surely, this net financial effect would be wholly counter-productive to the best interests of tenants generally.

24 The only real offences under the proposed new Regulations should be for refusing or

obstructing entry to, and inspection of, relevant premises, following receipt of a tenant's complaint or for refusing to comply with an official notice to repair and/or maintain a defective dwelling property up to a basic minimum standard of health and safety (as defined by the Law). Such offences should only be punished by proportionate fines (see explanation of this at paragraph 12(c) above).

However, whatever the legal process, it should not (in our view) be policed by ubiquitous annual inspections but solely by receipt of a complaint from a dissatisfied tenant, as always used to be the case. On receipt of any such complaint by the Environmental Health Department, an appropriate inspector already has: (a) a right of entry and inspection (by appointment with the landlord) and (b) the right to issue an appropriate enforcement notice with which the landlord must comply. This is also how the hospitality industry, in Jersey, and the Registered Lodging House sector, in Jersey, are both regulated.

Following compliance with an enforcement notice, a landlord must be permitted to increase the rent to the property's new market value, so as to reflect the improved quality of the property and provide the landlord with a reasonable return on his investment.

LEGAL PROTECTION FOR RESIDENTIAL LANDLORDS

25 Tenants are rarely (if ever) "bullied" out of their accommodation, as suggested by certain

politicians who are overly cautious or idealistic. In practice, no investor landlord will ever evict a good tenant. Why would they? The income from the tenant is the landlord's livelihood; whereas voids in occupancy or having to search for a replacement tenant inevitably reduces a landlord's revenue and profitability.

26 Not every landlord is a good landlord, of course; but, similarly, not all tenants are good

tenants. Regrettably, asking a tenant for references is not always a reliable method of avoiding bad tenants. Sometimes references are forged or written by friends of the tenant. As far as immigrant tenants are concerned, obtaining references from overseas landlords can be very time-consuming (if not impossible) and it can be even more difficult to establish how genuine any such reference actually is.

Consequently, there should be changes to relevant Jersey laws, specifically designed to give some protection to landlords. For example, if tenants do not pay their agreed rent or other expense commitments relating to the property, it should be possible to evict them much more quickly than at present. Also, if they materially damage or otherwise fail to maintain their accommodation to a reasonable standard, or if they permit more people to reside in the accommodation than permitted by their tenancy contract, speedy eviction should also be possible.

A grading system in respect of tenants and their families could be devised and maintained (just like the RentSafe scheme, which now provides tenants with grading information about Jersey landlords and their properties). This tenant's grading scheme could then be used by landlords for reference checking purposes. In the alternative, a black-list of delinquent tenants would achieve the same purpose, so long as it was permitted within the law.

27 Imagine a case where a tenant takes a lease on a hitherto well-maintained property.

Imagine that the tenant then becomes delinquent and, contrary to the terms of his tenancy agreement, either damages the landlord's property or otherwise lets it fall into a state of disrepair, due entirely to the tenant's own uncaring breach of contract.

Imagine that the lease or tenancy agreement obliges the tenant to maintain the property in specified ways; such as:

mowing the lawn; keeping drains and gutters clean and free from debris; fixing leaking tap washers and bath plugs; regularly wiping condensation from kitchen and bathroom walls; replacing defective light bulbs; disposing of refuse frequently and hygienically; repairing any of his own damage to the fabric or contents of the property so as to keep it at the same standard in which it was first handed over; and, finally, notifying the landlord promptly of any other maintenance issues that appear to need the landlord's urgent attention.

Imagine that the tenant begins drinking heavily and completely fails in all those agreed duties, resulting in a house that is physically sound as well as being wind and watertight but it has become dark, damp and mouldy, with leaking plumbing and rat and cockroach infestations; not to mention a jungle for a garden.

What would happen if the tenant then makes a formal complaint to the Environmental Health Department (or even to a Rent Control Tribunal if reinstated) about the state of the property.

It would surely be wholly unfair, in such circumstances, if a visiting inspector were to have no regard for who had caused all the damage, before issuing an enforcement notice against the landlord to carry out remedial work (at the landlord's own expense); possibly with notification of a fine or (possibly a reduction in rent) and/or cancellation of the property's letting Licence, for having failed to do the essential repairs promptly.

Imagine that the tenant refuses to pay for the repair work (which would obviously be his or her real cost) and the landlord runs out of money due to non-payment of rent by the tenant and, therefore, cannot afford to carry out the remedial work. Yet the delinquent tenant refuses to vacate the premises without an appropriate order from the court. In such circumstances (which do happen a few times each year), where would there be any protection at all, under the law, for the landlord?

Imagine that an unsympathetic inspector then cancels the property's Registration and letting Licence, on the grounds that the property has clearly become unfit for habitation. The landlord then loses further revenue until the property has been sufficiently reinstated to an acceptable standard and re-licensed for letting.

Yet there is no proposed provision in the law, which requires a tenant to comply with the terms of his lease or punishes him if he wilfully fails to do so, possibly at great personal cost to the landlord.

How is the Environmental Health Department proposing to deal with such scenarios? The fundamental point is that good landlords need protection from bad tenants in just the same way as good tenants need protection from bad landlords. Why are we seeing discrimination that favours bad tenants whilst not assisting good landlords?

Now imagine that the landlord, in this case, is actually a landlady who is also a frail (albeit reasonably healthy) 85-year old widow with no children but is fiercely independent, even though committed to the rest of her life in a wheelchair. How will she cope with this scenario, whereby the property quite probably represents her pension pot?

PROSPECTIVE EXPANSION OF UNNECESSARY CONTROLS

28 When rented dwelling accommodation is inspected, a natural follow-on by the inspector

would be to question whether that accommodation's space is adequate for the number of persons occupying it. Such space criteria are already set out in the laws relating to registered hotels and registered lodging houses. This same type of challenge, over habitable space per person in privately rented dwellings, would generate a whole new area of Regulation as to what space per person is deemed to be safe and healthy.

This aspect has not, so far, been raised by the Environment Minister, presumably because it would be too provocative for the owners of privately rented accommodation to accept (without howls of anguish) that there may be many 3-generation families, who may have to be evicted from properties that are too small for all of them.

The issue will, however, add a serious constraint on the number of people (particularly families with children and grandparents residing together in a single property). The prospective number is presently an unknown but could be ascertained by asking the question at the next census and collating the answers. However, the next big question would be: "who is then going to accept responsibility for rehousing those who have to be displaced by eviction, so as to be dwelling-space-compliant with any new Regulations, not yet drafted to control this issue?"

Such intrusive Regulation may, of course, then be followed by the opposite and even more intrusive proposition as to whether a particular tenant or family actually has too much space and should, therefore, (in order to be politically correct) be willing to share it with people who are homeless!!!

ONGOING NEED TO HOUSE IMMIGRANT WORKERS

29 Many short-term immigrant workers search for the lowest rent possible and will frequently

move house within Jersey in order to save just a few pounds per week, in rent. This decision is often taken regardless of the quality or condition of the accommodation either on offer or being vacated. Understandably, their priority in Jersey, is often to avoid superior quality housing with higher rents, in order to facilitate their sending back home as much of their Jersey earnings as possible. This repatriation of pay supports their families and pays the mortgage on a house in their home country.

If Jersey chooses to offer no low-priced accommodation at all, this omission would more than likely deter immigrants from choosing to come to Jersey for seasonal work in the first place. This case is especially exacerbated by the cost of transport to and from Jersey, the cost of paying for a registration card on arrival, the lack of healthcare benefit for six months after arrival, the cost of finding and renting accommodation in Jersey, all coupled with the high cost of living in Jersey generally.

30 Yet there is a desperately urgent need for immigrant labour to help run Jersey and to pay

a proportionate share of Jersey taxes and Social Security. In many cases, these workers are "short-term" employees such as seasonal agricultural and hospitality staff. Nevertheless, there are presently 200 vacancies at the Hospital, 20 teachers for Education, 70 chefs for Hospitality, an unknown number of other vacancies in the Civil Service, construction, agriculture, tourism and even hairdressing and the finance industry. Almost all Island businesses have been detrimentally affected by overly stringent constraint on the issue of employment licences.

31 We particularly need more immigrants because we need more tax-payers to pay the

pensions, health care and housing needs of the elderly who continue to grow older and have, over the last 50 years, quadrupled in numbers as a proportion of our population. As a rough rule of thumb, Jersey needs at least two tax-paying workers for every pensioner and we already have almost 35,000 pensioners, despite the recently announced increases in retirement age. But we do not yet have 70,000 or more full-time working adults, to generate the taxes the Island needs to balance its books.

32 The bottom line is that some of our politicians do not seem to recognise or understand the

costly extent and effect on Jersey's economy of having had a rapidly ageing population for the last 20 years or so.

33 A century or more ago, most people died by the age of 50. Half a century ago, people were

living to at 70 on average. But due to wonderful advances in medical science and healthcare, people are now living into their 90s.

34 The simple number of births over deaths is causing the population to increase by about

300 to 400 people per year. This annual increase requires 150 to 200 new units of accommodation per annum and this trend will likely continue and possibly grow, as the average age of death continues to rise; though there is presently a human skeletal age limit of about 120.

35 But the Government has taken approximately 20 years to begin admitting that the Island's

population will reach 125,000 or so within the next 10 to 20 years. Frankly, if medical science continues to progress, our population is more likely to be approaching 140,000. Honest projections of these figures need to re-assessed and published annually so that we can all know just how big our new hospital has to be, how many schools we shall need, how much water has to be in our reservoirs and how much has to be spent on better infrastructure, such as roads and cycle tracks and pavements and the bus service.

DETERRING HOUSING INVESTMENT BY PRIVATE LANDLORDS

36 To summarise some of the issues which have, in the last 7 years, acted as deterrents to

housing investment by private landlords:

o The 2013 Residential Tenancy Law went way beyond what was really necessary to protect tenants but, in particular, it contains not a word of legal protection for landlords as some justification for the Law.

o The 2015 Deposit Protection Scheme is hugely costly to tenants and administratively cumbersome – with deposit rebates taking weeks (and sometimes months) to be repaid. Very inadequate government statistics have been issued – eg £12.5m taken in deposits and removed from the Jersey economy. Is that in total to date (ie gross) or as held at present (ie net)? Ditto the value of fees taken by MyDeposits.Com. A more comprehensive table of MyDeposits.Com statistics should be published quarterly rather than annually.

o The JLA maintains that it would have been (and still would be) a much more efficient and cheaper option to adopt a different deposit protection scheme, such as the simple and inexpensive one we proposed in 2014.

o The 2017 voluntary Rent-Safe scheme had virtually zero take-up in its first two years. It is now effectively being used to blackmail landlords to join – or face significantly higher registration fees under the new Regulations for Registration of all rented housing in Jersey.

o The 2018 Health & Safety protection scheme for registered rental accommodation, now proposed for extension to ALL rented dwellings in Jersey, is quite likely very soon to be extended to EVERY dwelling in Jersey (both rented and owner-occupied). This is not because such an extension is needed but just to keep the increased number of Environmental Health inspectors in full employment.

SUNDRY CONCLUDING POINTS

37 One Jersey Government office with a single full-time civil servant could easily manage and

administer a deposit protection scheme as well as the arbitration of any resulting disputes between landlords and tenants. There are only 20 or 30 such disputes per year. Unlike MyDeposits.Com staff, that officer would be "on the ground" in Jersey and able to visit properties where photos are inadequate (eg it is impossible to photograph an unsavoury smell). He or she could also impose necessary discipline on delinquent landlords and delinquent tenants, including the maintaining of "blacklists" of the relatively few "baddies" on both sides. There's nothing to beat naming and shaming to ensure relatively inexpensive disciplinary control over the few individuals who spoil it for the rest. Perhaps we should bring back the stocks and the throwing of rotten tomatoes!

38 The proper way of dealing with this problem, politically and economically, is to cater fully

for the prospective population increase, including the taxation revenue that will have to be generated to cater for our elderly residents. One real (but, in the opinion of most landlords, highly undesirable) alternative would be to set about destroying our own economy so that people will leave Jersey in much greater numbers than are leaving the Island at present.

There are really no magic in-betweens that might make the local electorate happier and thus give our States Members a materially better chance of retaining their seats at each successive future election. Therefore, we must either opt for a strong and growing economy or a weak and falling economy.

A strong economy will bring with it a slowly growing population. This is because, in common with the rest of the world, almost every country has an ageing population, resulting almost entirely from improvements in medical science and Jersey cannot escape from this fact. So we need, for example, to be rather more selective in our choice of immigrant labour.

They must be able to demonstrate that they are honest, law-abiding, peaceful and have a responsible attitude; also that they have work experience with a skill that (however great or however humble), would make a desirable contribution to Jersey's economy and social wellbeing. This means being able to speak, read and write in English to a minimum specified level. A written agreement, in advance, not to contest deportation if ever convicted of a serious crime, would deter misconduct.

A weak economy will see a rapid fall in both population and in the price of houses. This second option will be good for those who want to see constraint in population growth and also for young people who are not yet on the housing ladder. However, the downside will be the collapse of the local business structure and a scarcity of jobs for those who are keen to work. There will also be greatly reduced government tax revenue, with which to pay for pensions and for healthcare.

39 As any immigrant workers (including short-term immigrant workers) will need to be

housed, of course. Yet Jersey's Government, on its own, does not have the money to fund this need, unless it is willing to borrow a further £1 billion to £2 billion to lend-on to Andium Homes for the provision of a great deal more social housing. According to the JEP, in a recent article on these new Regulations (3 October 2019, page5), Andium told them that any additional costs involved in providing accommodation would drive up rent prices and lead to less investment from landlords. This is a view with which the JLA entirely agrees.

40 In our view, discouraging private landlords from investing in more rented housing in Jersey

is an economically stupid and wholly flawed philosophy, as the wholesale abandonment of the private rented dwelling industry, will throw a much greater financial burden onto government and the tax-payer.

41 Those who believe that private landlords will not reinvest their funds elsewhere need to

visit the House of Commons Library and read the economic history of England between 1914 and 1984. During that 70-year period, the implementation of rent controls and protected (ie secure, long-term) tenancies decimated the number of private landlords from their ownership of 92% of all housing in 1914, down to only 8% in 1984. Since the UK government abandoned rent controls and implemented shorthold tenancies in 1984, that

8% figure has now recovered back to about 21%. Some 50% of all homes are now owner-occupied, whilst the remaining 30% balance of homes is social rented housing, provided by local authorities such as town and city councils.

42 Ironically, every home-owner in Jersey, who resides in a property which he or she owns,

can now reasonably wonder how soon it will be before these licence-fee and annual inspection Regulations (if adopted by the Assembly) are then extended to include ALL home-owners and ALL owner-occupied homes in Jersey.

Regrettably, this is not a humorous observation but simply a logical extrapolation of the annual licensing and mandatory inspection regime, presently being proposed for tenanted properties.

Some will say that a guaranteed basic standard of health and safety in the home is a "luxury" that ought not to be reserved solely for families who are tenants of a property rented to them by someone else! So, in order to avoid claims of governmental discrimination against Jersey's residential home-owners and their families, it would seem a fundamental right that they be equally entitled to enjoy a similarly guaranteed minimum standard of health and safety in the home.

Presumably, therefore, home-owners will soon be assisted in proving that they live in a "safe" and "healthy" home by being required to demand random visits to their homes every year or so (without prior notice) by government inspectors. The Ministry for the Environment would undertake to monitor the defect situation in each home in return for the payment by the home-owner of an annual "licence-to-occupy-fee". This fee would obviously be coupled with an undertaking also to pay for the prompt remediation of any defects found by the Inspectors.

The whole process will only become truly surreal when someone decides that it will be less expensive to place a CCTV camera in everyone's home so as to monitor remotely its state and condition. For better understanding, "1984" ("Big Brother is watching you"), written by George Orwell in 1949 is recommended reading.

43 Jersey seems to have become a community that can be relied upon to employ

sledgehammers to crack nuts. The Council of Ministers really needs to review all the promises to minimise red tape.

PAPER ENDS (8,136 words)

![]()

![]()

![]()

Jw/Word/JLA/PublicHealth&SafetyRentedDwellingsLicensingRegs2019-JLA-scrutinyPanelComment-21nov2019

![]()

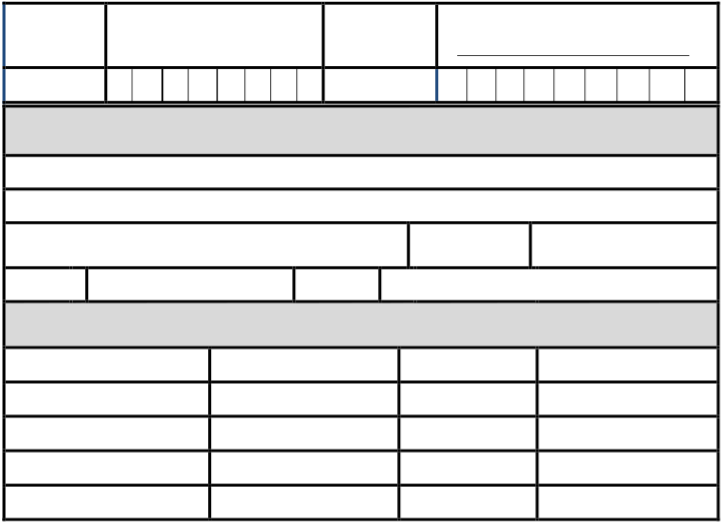

Notification of Change of Address Population Office

Notification of Change of Address Population Office

Control of Housing and Work Law (Jersey) 2012

Application under Part 4 of the Law – Any person who moves to an address in Jersey and is, or expects to be, ordinarily resident at that address for a continuous period of 3 months or more must notify the Minister.

Title |

| Mrs | Miss | Ms |

|

Surname Forename(s) Social Security

Surname Forename(s) Social Security

Date of Birth Number

Address of property occupied (Full postal address):

Postcode

Tel: Email:

List any other individual who has moved to that address with you below (include children of all ages)

Forename Surname Date of Birth Social Security Number

DECLARATION

I hereby notify the Minister of the change of address detailed above and declare that all the foregoing particulars are true and correct. By completing this form I acknowledge that the Population Office and the Customer and Local Services Department will be notified of my change of address.

Print Name Signature Date ![]()

The Chief Minister is registered as the Controller for data relating to Housing Control and Business Licensing for the purposes of the Data Protection (Jersey) Law 2018. The Housing Control and Business Licencing teams are part of Customer and Local Services and collect and process this personal data about you on behalf of the Chief Minister. Data collected may be made public. For information on how we use your data please go to our privacy statement on www.gov.je or request a written copy by phoning +44 (0) 1534 444444.

On completion, this application should be delivered to:-

Customer and Local Services, PO Box 55, La Motte Street, St Helier, Jersey, JE4 8PE