The official version of this document can be found via the PDF button.

The below content has been automatically generated from the original PDF and some formatting may have been lost, therefore it should not be relied upon to extract citations or propose amendments.

Affordable Housing: Supply and Delivery

Affordable Housing: Supply and Delivery

The Jersey Construction Council's response to the Environment, Housing and Infrastructure Scrutiny Panel's request for written submissions.

18 June 2021

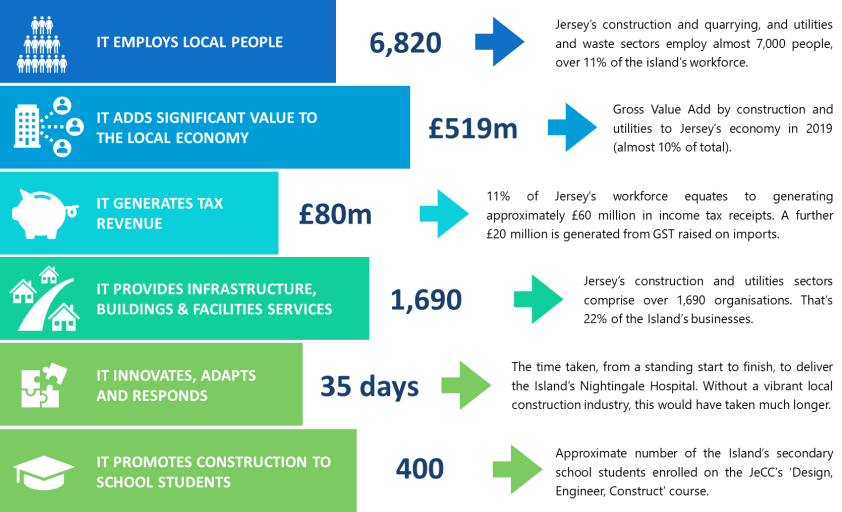

What does Jersey's construction industry do for the Island?

What does Jersey's construction industry do for the Island?

Jersey's construction industry and the JeCC

Jersey's construction industry and the JeCC

Jersey's construction industry provides the facilities and premises needed by the Island – the roads and infrastructure, housing, hospitals, schools, government buildings, community facilities – that serve the community in general plus premises the finance, retail, tourism and other industry sectors need to operate effectively.

The construction industry is Jersey's fourth most- valuable industry (by GVA). Almost 11% of the Island's working population depend on construction for their livelihood. Over 100,000 islanders depend on our services, goods and works to ensure the built infrastructure locally is delivered safely, efficiently and effectively.

A strong, healthy local construction industry is vital to the future economic success of Jersey as a whole (particularly as we respond to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on our local economy). Whilst some sectors can afford to specialise in order to compete on an international stage, Jersey's construction industry must only ever generalise, in order to continue to compete and deliver on the local stage.

The Jersey Construction Council (JeCC) is the voice of this industry Our list of over 130 members include clients (developers, Government agencies), utilities companies, contractors, subcontractors, suppliers, designers, and consultants.

![]() The JeCC occupies a unique role within the Jersey construction industry. The breadth and depth of its membership means that JeCC is the only body able to speak with authority on the diverse issues connected with construction without being constrained by the self-interest of any particular sector of the industry.

The JeCC occupies a unique role within the Jersey construction industry. The breadth and depth of its membership means that JeCC is the only body able to speak with authority on the diverse issues connected with construction without being constrained by the self-interest of any particular sector of the industry.

The JeCC's focus is on building Jersey better.

The JeCC is perfectly-positioned to take part in the EHI Scrutiny Panel review into making housing more affordable in the island. We see the challenge from both sides of supply and demand. We also see the challenge as end-users (as over 98% of our industry activity is delivered by on- island or local resource). The JeCC hope that this submission is informative and helpful.

Scope of the Scrutiny Panel review

Scope of the Scrutiny Panel review

"The Environment, Housing and Infrastructure Scrutiny Panel has launched a review examining affordable housing supply in Jersey.

![]() The review will investigate the challenges and barriers to development that are impacting on the ability to deliver more affordable homes. It will explore the relationship between planning and housing policies and how the Draft Bridging Island Plan 2022-25 seeks to address the supply issues and enable the delivery of more affordable homes. The Panel will also examine how other affordable housing policy mechanisms can be used, alongside planning policy, as part of a wider strategy to combat housing affordability.

The review will investigate the challenges and barriers to development that are impacting on the ability to deliver more affordable homes. It will explore the relationship between planning and housing policies and how the Draft Bridging Island Plan 2022-25 seeks to address the supply issues and enable the delivery of more affordable homes. The Panel will also examine how other affordable housing policy mechanisms can be used, alongside planning policy, as part of a wider strategy to combat housing affordability.

The Panel will explore the following key issues which have emerged:

- House prices are at an all-time high and without Government-led intervention, housing is becoming increasingly unaffordable for islanders.

- High land costs and challenges and barriers to development are impacting on the ability to deliver affordable homes.

- There is a lack of up-to-date strategy in relation to how planning policy can be used, in conjunction with other housing policy mechanisms, as part of a wider strategy to combat housing affordability and whether there are adequate Government resources to produce and deliver a strategy.

- The target for the delivery of affordable homes is an ambitious one given the timespan of the Bridging Island Plan 2022-25, and although the Housing Land Availability and Site Assessment has determined that there is capacity to cater for housing demand over the next 5 years, it nevertheless concludes that challenges will remain to ensure the complete delivery of affordable homes.

- Individual parishes have different models for the provision of first-time buyer homes, which lacks clarity and consistency of a joined-up policy approach.

- The Island Public Estate Strategy provides an opportunity to provide land for affordable homes, although the extent to which it will is currently not definitive. It is, however, estimated by the Government of Jersey that up to 425 affordable homes will be delivered from government-owned sites over the plan period. "

Our submission is in two parts:

Our submission is in two parts:

![]() Some ideas for A response to each of the managing the key price six key areas of focus of influencers in the the EHI Scrutiny Panel

Some ideas for A response to each of the managing the key price six key areas of focus of influencers in the the EHI Scrutiny Panel

availability of affordable review.

housing.

Part One

Part One

Some ideas for managing the key price influencers in the availability of affordable housing.

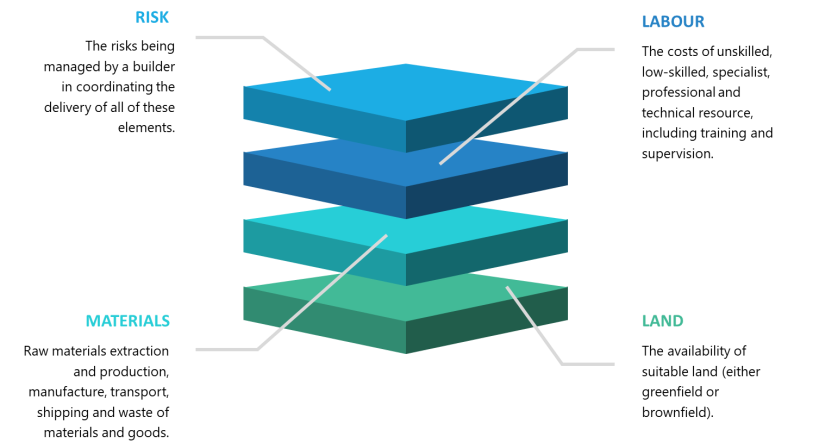

In Jersey, there are four main areas that have the most influence on costs of building.

In Jersey, there are four main areas that have the most influence on costs of building.

These input factors, more than any other, have the largest influence on the price of building in Jersey.

![]()

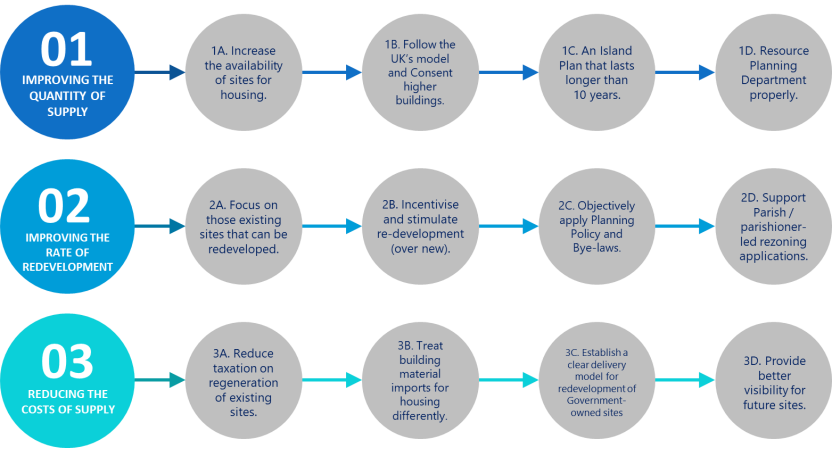

The JeCC's approach to making housing affordable focuses on three themes.

The JeCC's approach to making housing affordable focuses on three themes.

The three themes lead to 12 suggestions on ideas that will help to make housing affordable.

The three themes lead to 12 suggestions on ideas that will help to make housing affordable.

Part Two

Part Two

A response to each of the six key areas of focus of the EHI Scrutiny Panel review.

Within the responses, we have referenced each of the 12 ideas that we've provided.

"1. House prices are at an all-time high and without Government-led intervention, housing is becoming increasingly unaffordable for islanders."

"1. House prices are at an all-time high and without Government-led intervention, housing is becoming increasingly unaffordable for islanders."

The average earnings index (June 2020) from June 2001 to June 2020 shows a near zero increase (when adjusted for price inflation) (118.0 to 118.8 over the period, when 1990 = 100). Over the same period, the average price of a house in Jersey has risen by over 100% (when seasonally-adjusted).

![]() In June 2020, the average weekly earnings in the construction sector was £820.00, against an average all-sector earnings of £780.00. At the same time, average weekly earnings in the financial services and public sectors were £1,080.00 and £1,010.00 respectively.

In June 2020, the average weekly earnings in the construction sector was £820.00, against an average all-sector earnings of £780.00. At the same time, average weekly earnings in the financial services and public sectors were £1,080.00 and £1,010.00 respectively.

These are the factors that the JeCC believes are most-influencing the rising costs of house pricesonly those whose earnings that have maintained the pace of increase in house prices have been able to afford to purchase a house. The matter of house prices' and affordability' therefore needs to be seen not just in the context of the costs of the supply of housing, but also in the context of average earnings.

That cross-sector earnings have have failed to keep up with the price of housing over the past 20 years is not a problem unique to Jersey (numerous studies from OECD or World Economic Forum have found similar outcomes in both developed and developing countries). However, the problem in Jersey is compounded by: a) the relative scarcity of land either suitable for or zoned for residential development; and b) the willingness of the island's general population to accept a need for more homes to be created (sometimes referred to as NIMBYism'). And this is where the JeCC believes the collective agencies of Government SHOULD be investing their resource.

The JeCC believe that more supply will help – all other factors being equal – in the availability of housing (1A, 2A). This will help to meet the demand, and slow the present rate of house price inflation. More supply can only come from the availability of sites and the willingness of the Island-wide community to "play their part" and accept that without both the redevelopment of existing economically-obsolete stock and the identification of new sites (1A, 2A, 2C, 2D) , our children and grandchildren will find home ownership increasingly unaffordable.

Finally, a note on Government subsidisation of demand. Whilst the costs of wages in the construction sector are on a par with the mean sector average earnings, for example, those in financial services and public sector are presently an average 34% higher than the mean all-sector wage levels. Subsidising the initial costs of purchaseor rental payments does work (look, for example, at the success of the Government's recent assisted purchasing scheme; or indeed the successes in the past of the rent rebate' scheme that used to be operated by the Parishes). This is clearly to be encouraged and expanded.

The JeCC supports these schemes, though the means testing' that is used should clearly be focussed on those individuals and families that work in essential sectors that are paid lower than (for example) financial services. These schemes are though somewhat helpless and ineffective if there is not enough supply to meet the demand; and that is where the Island faces arguably its biggest challenge.

"2. High land costs and challenges and barriers to development are impacting on the ability to deliver affordable homes."

"2. High land costs and challenges and barriers to development are impacting on the ability to deliver affordable homes."

The availability or scarcity of land for housing development in the Island is managed by the Island Plan. The present Island Plan was agreed in 2011 and updated in 2014. The Island Plan is presently being updated with a bridging' Island Plan that – when approved – will last until 2025.

![]() The average small-scale (5 – 10 unit) housing development can take upto five years to complete (from inception to occupation), with significant-scale developments taking significantly longer (upto 10 years). The majority of this time is spent in pre-planning, planning and sourcing the permissions required to build, and the time period required for this activity has increased significantly over the past ten to 15 years, as the increased use of social media has led to more organised and active involvement in the planning process.

The average small-scale (5 – 10 unit) housing development can take upto five years to complete (from inception to occupation), with significant-scale developments taking significantly longer (upto 10 years). The majority of this time is spent in pre-planning, planning and sourcing the permissions required to build, and the time period required for this activity has increased significantly over the past ten to 15 years, as the increased use of social media has led to more organised and active involvement in the planning process.

Much of the island's town and urban area contain much existing housing stock that is economically- obsolete or run-down. JeCC calculations show over 2,000 units of accommodation (if developed) presently either in planning, in consultation or awaiting Planning Consent (via appeal or planning enquiry). These sites have the cheapest nett' cost per unit of accommodation with much of the infrastructure required already installed, and could be delivered swiftly following their consenting (3D).

The JeCC would also like to see the Island Plan incentivise the redevelopment of urban and town-centre sites for housing over the development of either new, countryside and Green Zone areas (2A). This could be done by following the UK Government's strategy of seed-funding redevelopment schemes that, for a variety of reasons, require works that impact their financial viability of make them cost-prohibitive for typical private-sector investment (e.g., the risks of contaminated land, impact of planning gain or planning supplement).

Finally, neither the present Island Plan or the Bridging Island Plan do anything to encourage the "intensification" of the development of this land to accommodate greater numbers of households (1A, 1B, 2B). In fact, present Planning Policy actually has the opposite effect: almost always referring to the height, mass, density of a site's surrounding areas as limits' to the scale / height / massing of new development. High-rise development is perceived or associated with social housing or poor-quality, 1970's drab housing blocks. However, in most major towns and cities in the UK, where demand for property outstrips supply, high-rise residential live / work' tower living has become desirable, resulting in significant numbers of low-cost units being provided by private-sector working in conjunction with local authorities and Planning agencies to ensure more social value impact is realised from this intensification of development.

"3. There is a lack of up- to-date strategy in relation to how planning policy can be used, in conjunction with other housing policy mechanisms, as part of a wider strategy to combat housing affordability and whether there are adequate Government resources to produce and deliver a strategy."

"3. There is a lack of up- to-date strategy in relation to how planning policy can be used, in conjunction with other housing policy mechanisms, as part of a wider strategy to combat housing affordability and whether there are adequate Government resources to produce and deliver a strategy."

The JeCC support this view. Work on the present Island Plan commenced over 14 years ago. The time taken to progress the Bridging Island Plan (2 years) is disproportionate to the time that it will remain in force for (3 years). It will require replacing in less than three years, which means the work on the next Island Plan will likely commence in 2023. This is an example of the counter-intuitive approach to developing planning policy: more time and resource is spent on developing and agreeing the policy at the expense of applying and implementing the policy.

![]() The matter of resourcing the Planning process is also of significance and one that the JeCC have been working on with the Planning Department. Despite the costs of Planning applications increasing at a rate far higher than inflation, the reasons provided by the Planning Department to our members for delays in processing Planning applications have become ever-more frustrating. There are presently over 500 Planning applications awaiting determination. The process of registering and validating an application (before the targeted 13-week determination period commences) has also become ever more longer. The Department target determination time for a Major Application is 13 weeks from validation, but often the registration period adds another 6 weeks to the process. Of 70 Major Application Planning approvals determined since the beginning of 2021, the average validation period was 6.52 weeks and the subsequent determination period was 16.16 weeks, or a total period of 22.68 weeks. This period of over five months excludes the subsequent time required due to either Third Party Appeals, or appealing the decision of a Planning Officer to the Planning Committee. The Planning process has become a significant challenge and a major factor in making housing projects affordable (1D).

The matter of resourcing the Planning process is also of significance and one that the JeCC have been working on with the Planning Department. Despite the costs of Planning applications increasing at a rate far higher than inflation, the reasons provided by the Planning Department to our members for delays in processing Planning applications have become ever-more frustrating. There are presently over 500 Planning applications awaiting determination. The process of registering and validating an application (before the targeted 13-week determination period commences) has also become ever more longer. The Department target determination time for a Major Application is 13 weeks from validation, but often the registration period adds another 6 weeks to the process. Of 70 Major Application Planning approvals determined since the beginning of 2021, the average validation period was 6.52 weeks and the subsequent determination period was 16.16 weeks, or a total period of 22.68 weeks. This period of over five months excludes the subsequent time required due to either Third Party Appeals, or appealing the decision of a Planning Officer to the Planning Committee. The Planning process has become a significant challenge and a major factor in making housing projects affordable (1D).

The JeCC would like to see an Island Plan that is directly-mapped to an immigration and population policy the Planning Department being resourced and operated efficiently to implement it (1C, 1D. 3D)Once an Island Plan is agreed, the Plan should be worked within, with only matters of architectural style and scheme design left to be resolved through the Planning process (2C). Future Island Plans should be reactive to changes in circumstances. The Government should ensure a fit-for-purpose, independently-regulated Planning Department is maintained, one that works to a service-level agreement, and with industry to identify those resources required to manage future Planning applications (1D). The process of validating a Planning application should be automated, and user-driven through an online portal. This would relieve the Planning Officer of the need to validate, and ensure that the Applicant and the Agent submitting have the responsibility to include all the required documents, in the required format, at the outset. The Planning Department provide more objective, professional upfront advice and guidance on the application of Planning policy to a particular scheme. Our members would willingly pay for a pre-application consultancy and advisory services (several of them already routinely invest sums in planning advisory services). However, were this service to be linked to those delivering the Planning service, it would provide better visibility early on about the planning risks associated with a particular scheme (1D, 3D).

Finally, the JeCC would also propose an Island-wide public register of land ownership which identifies the costs of sale of the land at the last transaction, similar to the Land Registry in the mainland UK. The use of the register could increase the transparency of land prices in the island, and enable better benchmarking and valuation outcomes, particularly for that land in a given Planning Use Class (3D). This approach will ensure greater certainty and reduce the costs of land supply through auction or open sale (3D).

"4. The target for the delivery of affordable homes is an ambitious one given the timespan of the Bridging Island Plan 2022-25, and although the Housing Land Availability and Site Assessment has determined that there is capacity to cater for housing demand over the next 5 years, it nevertheless concludes that challenges will remain to ensure the complete delivery of affordable homes."

"4. The target for the delivery of affordable homes is an ambitious one given the timespan of the Bridging Island Plan 2022-25, and although the Housing Land Availability and Site Assessment has determined that there is capacity to cater for housing demand over the next 5 years, it nevertheless concludes that challenges will remain to ensure the complete delivery of affordable homes."

The JeCC disagrees that the target for the delivery of affordable homes is an ambitious one. Further, the target should also be wholly-unrelated to the delivery of any Island Plan (the Island Plan should be simply an ordinary course of normal business for the Planning Department and it should not have any influence on diverting or impacting business as usual).

![]() We believe the reason why the target is perceived as ambitious is because of the lack of any real cohesion between the different agencies of Government that are responsible for achieving it. Planning, for example, are not incentivised to meet any targets on housing numbers. Neither are Treasury Department. Nor indeed the IHE Department. Indeed, even the Government's social housing provider, Andium Homes, aren't under any financial or non-financial incentives to realise their own target of housing numbers. So, without any collective focus across these agencies – linked to incentives – why should they allocate resource to focus on working with industry to deliver a target' (which, without repercussions associated with not achieving, is simply a marker in the road that keeps getting moved further and further away) (1A, 1D, 2B, 3D).

We believe the reason why the target is perceived as ambitious is because of the lack of any real cohesion between the different agencies of Government that are responsible for achieving it. Planning, for example, are not incentivised to meet any targets on housing numbers. Neither are Treasury Department. Nor indeed the IHE Department. Indeed, even the Government's social housing provider, Andium Homes, aren't under any financial or non-financial incentives to realise their own target of housing numbers. So, without any collective focus across these agencies – linked to incentives – why should they allocate resource to focus on working with industry to deliver a target' (which, without repercussions associated with not achieving, is simply a marker in the road that keeps getting moved further and further away) (1A, 1D, 2B, 3D).

The JeCC completely support the good work that Andium and other registered social landlords (RSLs) are doing to meet the Island's future housing needs. However, the RSLs – and all developers / imvestors / providers for that matter – have no control over the processes required to meet the target. The recent examples of the Tunnell Street (former Gas Works) and Ann Street Brewery sites, where over 400 units of social accommodation in town locations adjacent to the Millennium Park have been either delayed or curtailed, serve as a reminder of how difficult the Island's present Planning system makes the achievement of any sort of target possible (1A, 1B, 1D, 2A, 2B, 2C).

The Housing Land Availability and Site Assessment has indeed determined the capacity is available to meet the target. And the former Planning Committee Member (and now Minister for Housing) Deputy Labey himself has published a plan only this week setting out an aim' for delivering over 1,000 units. Further, the Bridging Island Plan has identified sites throughout the island for over 1,500 units. Yet, as a cross-industry representative body, the JeCC have very little confidence in any of these targets, aims or aspirations being met under the present disaggregated approach to planning their delivery.

The JeCC note that the capacity of the construction industry to meet the target is not, by itself, a factor in achieving any of the targets published. For example, 1,250 new homes over five years equates to 250 completed homes each year. The local construction industry, with the notice and early-engagement, is more than capable of meeting this target. Finally, it is worth remembering that, when a contractor is appointed to deliver a housing development, they are always incentivised through a number of ways (payment, damages for late completion, key performance indicators) to achieve the completion date. The JeCC would like to see more use of the Government's not inconsiderable influence to incentivise other parts of the development process and provide better visibility on a Planning pipeline' that can be used to allocate resources in the future to resolve and approve these Planning Consents (1D, 3D).

"5. Individual parishes have different models for the provision of first- time buyer homes, which lacks clarity and consistency of a joined-up policy approach."

"5. Individual parishes have different models for the provision of first- time buyer homes, which lacks clarity and consistency of a joined-up policy approach."

The JeCC supports this assertion. The JeCC also notes that rules applicable to each of the models differs between Parishes, making it very hard for potential first-time buyers (FTB) to understand how to qualify. It is also arguable that there is a lack of transparency on the criteria required to qualify for a Parish first-time buyer scheme, and the way that members of the Parish sometimes apply the criteria.

![]() However, the JeCC does not agree that this, in itself, is a significant issue in respect of making homes more affordable. For whilst there are obvious problems arising from the registering and qualifying processes for the Parish FTB projects, the fact is they at least count as homes being made available to meet FTB demand, and that is something to be encouraged given the patent (rising) demand for new homes on the island. This, more than any centrally-controlled process, should be supported and incentivised (1A, 1C, 2D).

However, the JeCC does not agree that this, in itself, is a significant issue in respect of making homes more affordable. For whilst there are obvious problems arising from the registering and qualifying processes for the Parish FTB projects, the fact is they at least count as homes being made available to meet FTB demand, and that is something to be encouraged given the patent (rising) demand for new homes on the island. This, more than any centrally-controlled process, should be supported and incentivised (1A, 1C, 2D).

The real issue with Parish support for FTB schemes is one of land-use and constraining the Planning Use Class to its present historical use. Several Parishes have recently applied for sites in their parish to have their present Planning Use Class changed from agricultural or Green Zone to housing as a part of the Bridging Island Plan, and were unsuccessful. The next opportunity they will have to do this (noting that any further change of use' applications are now being deferred until after the present Bridging Island Plan) could be as late as 2025. A change of use application can take anything up to 18 months to realise. Then there is the applications for Planning Consent and Building Bye-law permissions (another 18 months). So, it may be 2028 before work even starts on some of these sites (which, it must be remembered, were potential development sites SUPPORTED by the Parishes and their parishioners when making the representations to the Bridging Island Plan) (1A, 1D, 2D).

The JeCC believes the present approach to controlling the use of land within a parish is flawed and simply isn't consistent with a modern government. In the UK, most regional planning matters are devolved to local and regional planning authorities, which are resourced by county and city councils who are elected locally to hear argument and apply locally-set planning policy. Further, devolving decision-making from centre to outset has been a key aspect of the legislative framework in the UK and western Europe for some time now.

In Jersey, we feel that the Government needs to be able to permit the parishes to have a greater say in their own planning and development matters. Together, the Government and the parishes should devise a scheme that will encourage parishioners and Parish governance to interact and identify ways of accommodating more FTB homes and the community-based infrastructure (shops, hospitality, etc.) to support them (1A, 1D, 2D, 3D).

Finally, the JeCC notes that the matter of Parish allocation and management of FTB homes within their communities should not cloud the bigger picture: the overall need to deliver more affordable housing. This can only come from improving the quantity of supply, decreasing the spend on supply, and helping to manage the demand (1A, 3A, 3B, 3D).

"6. The Island Public Estate Strategy provides an opportunity to provide land for affordable homes, although the extent to which it will is currently not definitive. It is, however, estimated by the Government of Jersey that up to 425 affordable homes will be delivered from government-owned sites over the plan period."

"6. The Island Public Estate Strategy provides an opportunity to provide land for affordable homes, although the extent to which it will is currently not definitive. It is, however, estimated by the Government of Jersey that up to 425 affordable homes will be delivered from government-owned sites over the plan period."

The JeCC supports this approach. The situation of the former Les Quennevais School, which was left dormant for 18 months after the opening of the new school despite the Government having eight years notice of the date that it proposed to vacate, serves as a timely example of what the Government must word to avoid in the future. (Note: there is still no permanent plan for the development of the former school, and but for the temporary use arising as a part of the Our Hospital programme, it would still remain vacant as we speak). The Government simply must get better with the management and disposal of its redundant estate.

![]() The Island Public Estate Strategy is strong on promise, but yet again weak on firm, measurable, committed dates that it will achieve (and be measured by). The JeCC would like to see the allocation /.management / disposal of these sites undertaken through open and transparent tendering procedure that ensure: a) the Government agencies that might ordinarily be allocated these sites are tested in competition as providing the best value' solution; and b) the private-sector is afforded the chance to benefit from their availability and take on the risks of achieving the successful outcome at no risk to the taxpayer (1A, 3D).

The Island Public Estate Strategy is strong on promise, but yet again weak on firm, measurable, committed dates that it will achieve (and be measured by). The JeCC would like to see the allocation /.management / disposal of these sites undertaken through open and transparent tendering procedure that ensure: a) the Government agencies that might ordinarily be allocated these sites are tested in competition as providing the best value' solution; and b) the private-sector is afforded the chance to benefit from their availability and take on the risks of achieving the successful outcome at no risk to the taxpayer (1A, 3D).

It is argued that the agencies' of Government provide value to the taxpayer through reinvestment of all profits back into the Government. However, the fact remains that the risks of development are only ever managed or underwritten by the Government. It should not be for the Government to manage those risks that there is ordinarily a willing, capable, market already available. The workings of the Government's Regeneration and Steering Group and Council of Ministers are not fully-visible to the public, meaning that the process of site allocation is neither transparent or tested through competition (how are the assertions being made at either RSG or COM by a public agency tested for bias or authenticity?).

The JeCC would like the process of disposal of any Government sites to have more transparency: a) sites for sale should be advertised and tenders pitted against each other; b) factors other than price (e.g., scheme design quality, social value impact, levels of profitability, tax generated, time to deliver) should all be scored and evaluated; and c) commitments to deliver on the schemes proposed within given time constraints should be made binding on the successful tenderer. Weighted criteria, stated at the outset, should be published and applied. An electronic tendering system should be used to ensure standards of probity and transparency are met. Advisors should be appointed to validate assertions made by tenderers (1A, 2A, 2B, 3C, 3D).

The JeCC would also like to see a visible timetable of when these sites will be made available for development (3D). The present Island Public Estate Strategy contains no roadmap' or targeted series of milestones when the sites will be released for development. (It is worth noting that 425 affordable homes now will have a significant impact on local supply; in ten years, with similar circumstances to those at play at present, this may not have as significant an impact) (1A, 3D).

Finally, the JeCC would like to see the Planning Department provide Supplementary Planning Guidance on their expectations for Planning Use Class of these sites (1C, 1D, . The example of the existing Cyril Le Marquand House, in which a SPG was published in February 2020 identifying not just the potential use of the site as residential or offices but also confirming their aspiration for the type of residential use (in this case key worker' housing) is noted. This advice was helpful to ensure that time was not wasted progressing a scheme that would not have met with Planning policy. Similarly, Guernsey's use of Development Frameworks is another good example of early visibility on aspired uses for a particular site. This information is much-needed to ensure organisations are able to help respond to the demand for more affordable housing (1A, 1D, 2B, 2C, 3D).

![]() The Jersey Construction Council (JeCC) is the voice of the island's construction industry. Our focus is on building Jersey better.

The Jersey Construction Council (JeCC) is the voice of the island's construction industry. Our focus is on building Jersey better.

Our 130 member organisations include clients (developers, Government agencies), utilities companies, contractors, subcontractors, suppliers, designers, and consultants. The JeCC occupies a unique role within the Jersey construction industry. The breadth and depth of its membership means that JeCC is the only body able to speak with authority on the diverse issues connected with construction without being constrained by the self-interest of any particular sector of the industry.

This document has been prepared by the JeCC as a response to the request for written submissions made by the EHI Scrutiny Panel. This document contains the views of the JeCC as a collective, and does not comprise the views of any one individual within the JeCC. It contains the views on those matters identified as areas for consideration in the document.

Any comments or requests for further comment from the JeCC shall be directed to the address and contact below.

Jersey Construction Council Limited

Company registered in Jersey, Channel Islands. Company registration number 87793

Level 2, 1 Brittania Place St Helier

Jersey JE2 4SU

Channel Islands, UK

+44 (0)1534 725417 info@jerseyconstruction.org

www.jerseyconstruction.org