The official version of this document can be found via the PDF button.

The below content has been automatically generated from the original PDF and some formatting may have been lost, therefore it should not be relied upon to extract citations or propose amendments.

Common Population Policy - Submission to Scrutiny Jonathan Renouf : Jan 2022

Introduction

I welcome the publication of the Common Population Policy, and the accompanying report. It is particularly significant that the Council of Ministers have reinforced their commitment to progressively reducing the island's need for inward migration, with the aim of achieving a stable population.

However, beyond this simple principle, the report lacks ambition.

- It fails to make any kind of historical analysis, making it impossible to judge the success or failure of current and previous population policies.

- It attempts a sleight of hand that cannot be allowed to stand. In arguing that it is too soon to set any population targets, it perpetuates the myth that there is no current population policy. Clearly there are immigration rules currently in place. Someone is deciding who can gain a permit. The government must spell out its current immigration

policy.

- Finally, it is not tenable to argue that four more years of data collection are required before a new population policy can be formulated. This is policy paralysis that would be unacceptable in any other area of government business.

Background

When the Council of Ministers established its priorities shortly after the 2018 election, one of its main promises was:

"We will establish a Policy Development Board to develop an agreed population and migration policy that balances population pressures against economic and environmental needs."

Almost four years on, and we're still waiting. In fact, even on a best case scenario, we'll be waiting another four years before we get a new policy. That's eight years from the time the need for such a policy was announced. Yet even this does not capture the scale of the public policy failure on immigration and population. Despite widespread public concern, not since 2009 have the States Assembly debated setting a target for immigration. At that time, the figure of 325 a year became the "planning assumption", built into various government plans, and in particular baked into the Island Plan. Yet this figure was breached by very

large amounts in every one of the subsequent years.

Rather than reacting to this failure by trying to get back in control of the situation, the previous Council of Ministers abolished the post of Population Minister, and effectively abandoned population targets and immigration limits. This situation was however arrived at by default - no proposition was ever brought to the States Assembly to explain or legitimate this decision. Neither was any attempt made to align other aspects of government policy with the move to mass immigration. The Island plan - which had been designed to meet a housing need predicated on a population increase of 325 a year - was not changed. Unsurprisingly the result was a housing supply and affordability crisis that has escalated in scale ever since. Mark Boleat's 2010 report on population emphasises what a predictable outcome this was:

"Ifland is not made available [for housing] then the effect of rising immigration is to increase house prices." (Jersey's Population - A History, 2010, page 7)

Taken together, the failure to secure democratic consent for a de facto policy of mass immigration, the failure to align government planning with the realities of immigration levels, and the failure to bring forward new population policies despite repeated promises to do so must count as one of the most egregious and damning public policy fiasco's in the island's history.

It is a failure that has undermined faith in the entire process of government. It has exposed the governing class as weak and unable or unwilling to lead on an issue of primary concern to a majority of islanders. Ultimately it has also been self defeating. The housing (and related cost of living) crises have led to considerable labour shortages and almost certainly some outward migration. In other words, excessive immigration has undermined the economy, the very opposite of what it was supposed to achieve. Now, as a result of these failures, the massive rise in the island's population over the last decade has been used as a battering ram to fundamentally change planning policies, unleashing a wave of housebuilding on a scale and at a pace never seen before in the island's history.

In the face of all this, we are still being told that there is not enough information to set a population policy for the next 4 years. This stance does not stand up to examination.

In this short paper, I lay out some relevant information that has not been examined in the Population proposition and which Scrutiny may wish to consider. I end with a number of recommendations.

1) Context

It is important to establish that over the last 10 years (until 2019, the last year for which meaningful statistics are available), Jersey's net immigration levels were amongst the highest in the world. If Jersey were a country it would step confidently into the top 10 in the league table of countries with the highest immigration levels (see table below). It is important that politicians realise that Jersey's recent immigration policies make the island an outlier. It is not unreasonable for the public to have concerns about the speed at which the island is changing, once this context is understood.

Table: Annual net immigration per 1000 inhabitants

|

| 2015–2020 (forecast) |

| 31.1 | |

| 22.8 | |

| 18.6 | |

| 16.3 | |

| 14.7 | |

| 12.4 | |

| ||

| 9.9 | |

| 9.8 | |

| 8.0 | |

8.0 | ||

| 7.4 | |

| 6.6 | |

| 6.6 | |

| 6.4 | |

| 6.1 | |

| 6.0 |

5.3 | |

4.9 | |

4.7 |

Note that in this table, Jersey is grouped with Guernsey. In fact, Guernsey's net immigration level was close to zero, and so Jersey's average net immigration figure was actually around 12 per thousand. Other than Luxembourg, no other developed nation comes close to this level. (Source: World Population Prospects, United Nations, 2019)

2 Current policy

It is incorrect of the government to argue that we have to wait four years for a population policy. We already have a population policy; it is just that the government does not wish it to be revealed or discussed. The accurate way to phrase the government's policy is: "We do not wish to CHANGE the current policy for another 4 years".

Clearly, immigration is happening. Someone, somewhere, is making decisions about who can and cannot come to the island. With births and deaths roughly cancelling each other out, immigration policy is effectively population policy. Failure to discuss current policy seems to be aimed at maintaining maximum freedom for manoeuvre with minimum accountability. This is not good enough. We need to be told what policy is currently being pursued.

The existence of a de facto population policy is also clear from the various assumptions that are used by government in various planning documents. These congregate around plus 700 to plus 1000 a year. According to the report, the aim of policy is to reduce reliance on inward migration - yet these planning assumptions suggest that if there is to be a reduction, it is going to be minimal. Once again, this points to the urgent need for clarification around current immigration and population policy.

It is also worth pointing out that current policy is not being held to the same standard as a potential future policy. According to the government, we do not have enough information to pursue a new policy, but apparently we do have enough policy to continue with existing policy. This exposes the gaping hole at the centre of the report: there is no analysis of the benefits and costs of immigration policy as it has been pursued over the last twenty years. The underlying assumption is that it is safer to stick with existing policy rather than risk adopting a new one. However, this assumption is entirely un-evidenced. Once the experience of the last twenty years is examined, it is clear that current policy has been disastrous, even on its own terms. Waiting (at least) another four years before changing policy in these circumstances is reckless.

3) Economic growth and migration

For decades, islanders have been sold a story that immigration was good for economic growth. The economy could not grow without the labour market being "topped up" from outside. In practice this boiled down on the one hand to a demand for low wage labour in the hospitality sector and the rural economy, and on the other hand the need for highly skilled workers to fill gaps at the top of the labour market (particularly in finance). What were the results? Jersey's economy has essentially flatlined. In terms of per capita economic growth, the economy has not grown for 20 years. It is striking that the government's report contains no analysis of the supposed link between growth and immigration, even though this was the rationale behind the policy.

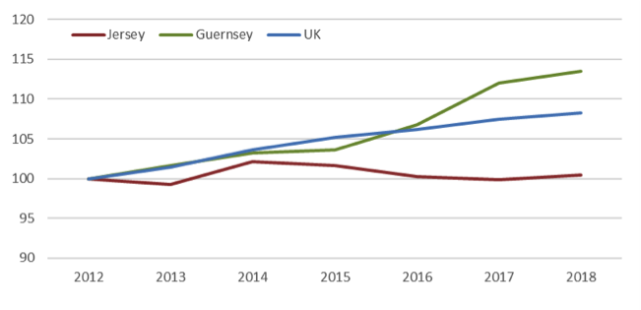

This is particularly surprising, given that there is a comparison right on our doorstep. Guernsey has seen virtually no population growth and yet its economic output per capita has grown considerably (see graph below).

The year 2012 is taken as a baseline (100) (Source: Statistics Jersey)

Guernsey has outperformed Jersey economically with a virtually stable population. The government should analyse the experience of Guernsey to see what lessons can be learnt. If the comparison with Guernsey has no relevance to Jersey, then we should at least be told why this is the case.

4 Dependency ratios

Whenever the subject of immigration is raised, so too is the subject of dependency ratios. Many tables are produced in the report that show the supposedly positive impact of higher levels of immigration on dependency ratios. They are grossly misleading.

If we look at predictions of dependency ratios from 20 years ago, we see that despite high levels of immigration, dependency ratios have worsened significantly. In the year 2000, the government published a report that examined the future of the Social Security Fund. It laid out predictions for the old age dependency ratio; that is, the ratio of people of working age to people of retirement age. A higher figure is obviously better; it means more workers paying taxes to support the elderly.

Assuming net immigration of 200 a year, the report said that the old-age dependency ratio would be 2.6 in 2060; in other words there would be 2.6 workers for each person over 65. Since then, we've had immigration much higher than 200, which should have substantially improved the outlook for the dependency ratio. So what actually happened? The most recent update of the dependency ratio figures was published in 2016. The nearest comparison to the predictions published in 2000 is for net immigration of 325 a year, which by the year 2065 yields a dependency ratio of 2.1. So despite all those years of high immigration, we've ended up with a worse old-age dependency ratio than was forecast in the year 2000.

How can this be so? There's a clue on page 12 of PWC's "Ageing Population" report produced in November:

"Looking ahead the dependency ratio is likely to accelerate in the next two decades given the significant inward migration of young people to Jersey in the 1970s and 1980s - who are getting close to pension age." (Impacts of an Ageing Population on Jersey's Economy, Nov 2021)

In other words, increasing immigration reduces the dependency ratio in the short term, but at the expense of increasing the dependency ratio in the longer term. This is an iron law that cannot be evaded. The failure to acknowledge this simple truth risks condemning the island to be forever chasing its tail. Only by stabilising population can we stabilise the dependency ratio. Otherwise in another 30 years we can look forward to another report that repeats the quote above with a very minor variation: "Looking ahead, the dependency ratio is likely to accelerate given the significant inward migration of the 2010's and 2020's"

5 False predictions

Another problem with all the dependency ratio scenarios in the report is that they are based on a retirement age of 65. This makes the figures look a lot worse than they actually are, because in fact Jersey's retirement age is scheduled to rise to 67. On its own, this single factor reduces the long term dependency ratio by around 6% (source: email communication from Statistics Jersey). In other words - to pick an example at random - the 2065 predicted dependency ratio for a plus 700 scenario drops from 68% to 62%.

Once Jersey's actual retirement age is factored into dependency ratio calculations, we compare very favourably with other jurisdictions. It is alarmist to use dependency ratios based on an incorrect retirement age; this should be acknowledged in the report, and dependency ratios produced in future that reflect the actual retirement age in Jersey.

6 Alternative scenarios

Various population scenarios are modelled in the Proposition but one critical option is missing; a stable population policy. This differs from a "net nil migration" scenario (which is modelled) because it is dynamic: as fertility declines, immigration increases to compensate. This is particularly surprising given that the report identifies a stable population as the ultimate objective of government policy. It is also important because a stable population policy allows immigration to gradually but steadily increase over time, to compensate for an ageing population. Finally, a stable population policy will have better

long term outcomes for the dependency ratio.

Modelling the dynamic immigration scenarios necessary to achieve a stable population is likely to be complex, but it is vital if we are to make properly informed decisions.

7 Importance of immigration

None of these comments are intended to suggest that immigration is unimportant to Jersey. Quite the reverse. Jersey is an immigrant island - it always has been and always will be. We need migrants to bring skills to the island, and to compensate for declining fertility. Particularly at a time of intense uncertainty, it makes sense to maintain flexibility in immigration policy for a limited period. However, even within this framework, it should be possible for the Council of Ministers to give some idea now about what size of population it believes is sustainable in the long term.

- Quality of life

Whilst the government prefers to see population as the outcome of other factors that control our quality of life, for most islanders population is in itself a factor that affects quality of life. The island's identity will change profoundly if population is allowed to rise to

- let's say - 150,000. This would be a crowded island with a proliferation of high rise buildings and considerable encroachment of the built environment into the countryside. It may bring a notionally higher economic output, but this would be an island that many people would not like to live in.

Questions of population are therefore not just about the economy. They are about identity, the environment and wellbeing, amongst many other issues. The government's report is reductionist in its focus on the economy. It would be helpful if the issue of population was considered alongside other government initiatives such as environmental policies and the carbon neutral strategy. In focusing almost exclusively on the perceived needs of the economy, there is little opportunity for population policy to also reflect wider issues. To put it most bluntly: there is a strongly held view - that I share - that we should be prepared to

sacrifice some economic growth in order to preserve our quality of life.

If the report accompanying the proposition had not dedicated so much time to explaining why the can should be kicked down the road, then there might have been space to consider these trade offs. Instead, the report returns to the overused mantra that a "balance" needs to be struck, without ever explaining where the balance might lie.

- Setting a new population target

It is simply untenable to argue that no new population targets can be devised for another four years. The government could for example publish a population range rather than a single target. It could also qualify this range by saying that it may need to be revisited in the light of circumstances. Without some kind of figure, we are accepting policy paralysis on one of the most important issues facing the island. The suspicion is that the failure to set a population target reflects more the inability to achieve a political consensus than a lack of data.

Recommendations

- The Council of Ministers must publish and explain its current Immigration/Population Policy as a matter of urgency.

- The government should analyse the impact of existing population policies on the economy, the environment and quality of life.

- Future modelling of dependency ratios should include a "stable population" scenario.

- The dependency ratio should be modelled on the basis of the actual retirement age (67), not the old retirement age (65).

- At the very least, the government should publish an indicative range for where it believes Jersey's stable population should be set.