The official version of this document can be found via the PDF button.

The below content has been automatically generated from the original PDF and some formatting may have been lost, therefore it should not be relied upon to extract citations or propose amendments.

STATES OF JERSEY

r

DRAFT TELECOMMUNICATIONS (AMENDMENT No. 3) AND CRIME (MISCELLANEOUS PROVISIONS) (JERSEY) LAW 201-

![]() Lodged au Greffe on 1st March 2016 by the Chief Minister

Lodged au Greffe on 1st March 2016 by the Chief Minister

![]() STATES GREFFE

STATES GREFFE

2016 P.19

DRAFT TELECOMMUNICATIONS (AMENDMENT No. 3) AND CRIME (MISCELLANEOUS PROVISIONS) (JERSEY) LAW 201-

European Convention on Human Rights

In accordance with the provisions of Article 16 of the Human Rights (Jersey) Law 2000, the Assistant Chief Minister has made the following statement –

In the view of the Assistant Chief Minister, the provisions of the Draft Telecommunications (Amendment No. 3) and Crime (Miscellaneous Provisions) (Jersey) Law 201- are compatible with the Convention Rights.

Signed: Senator P.F.C. Ozouf

Assistant Chief Minister

Dated: 17th December 2015

![]() REPORT Background

REPORT Background

The digital world moves extremely rapidly and any legislation in this area runs the risk of quickly becoming outdated. New devices are emerging at an unprecedented rate, and consumer behaviour is changing in often unpredictable ways.

It is important that the relevant authorities in Jersey have the ability, in appropriate cases, to prosecute people for sending communications that are grossly offensive or of an indecent, obscene or menacing character, including via social media. As part of this, the law should enable the appropriate authorities to tackle behaviour that constitutes cyberbullying.

On 15th October 2015, the Assistant Minister for Economic Development made a Ministerial Decision approving instructions to the Law Draftsman to prepare amendments to the legislation applying to harmful electronic communications (see MD-E-2015-0088). The purpose of these amendments is to ensure that the legislation in Jersey continues to effectively deter the sending of harmful online communications and provides appropriate and lasting protection for the Public, whilst also ensuring that it does not have a chilling effect on free speech. In short, it should allow for people in Jersey to take full advantage of the opportunities offered by new technology, safe in the knowledge that they will be appropriately protected by the law in so doing.

On 30th November 2015, the Minister for Home Affairs made a Ministerial Decision approving instructions to the Law Draftsman to prepare amendments to the legislation applying to restraining orders (see MD-HA-2015-0078). The purpose of these amendments is to ensure that legislation in Jersey continues to deter the commission of disorderly conduct and harassment and provides appropriate and lasting protection for the public.

Research and consultation

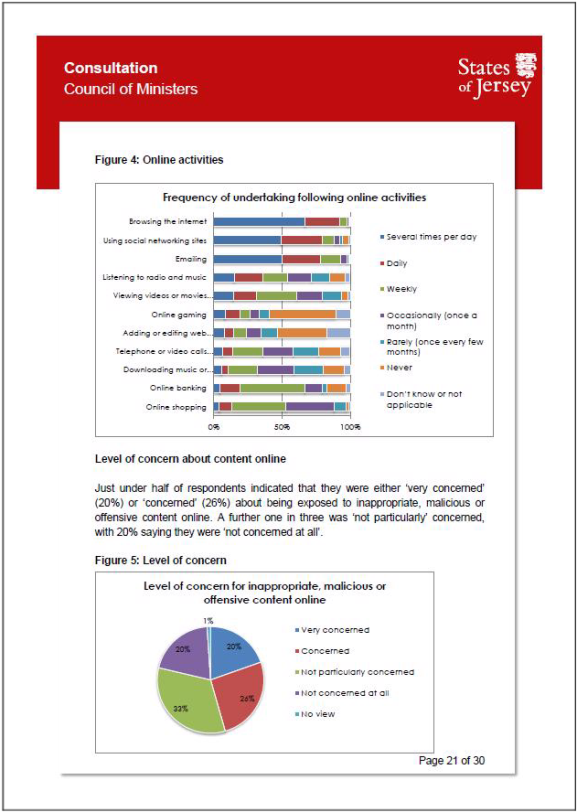

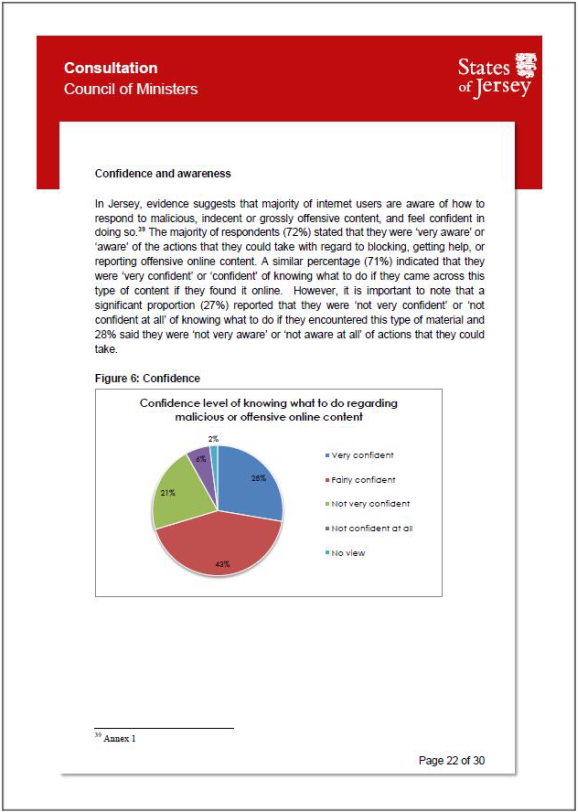

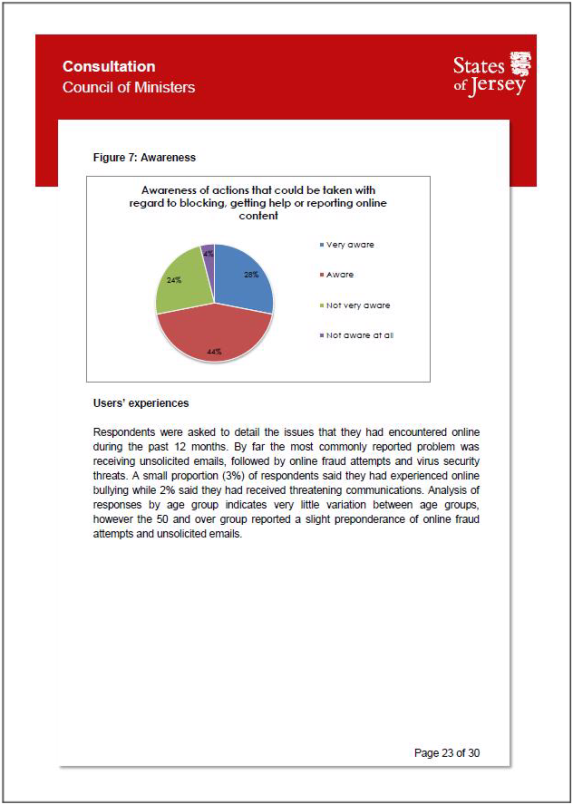

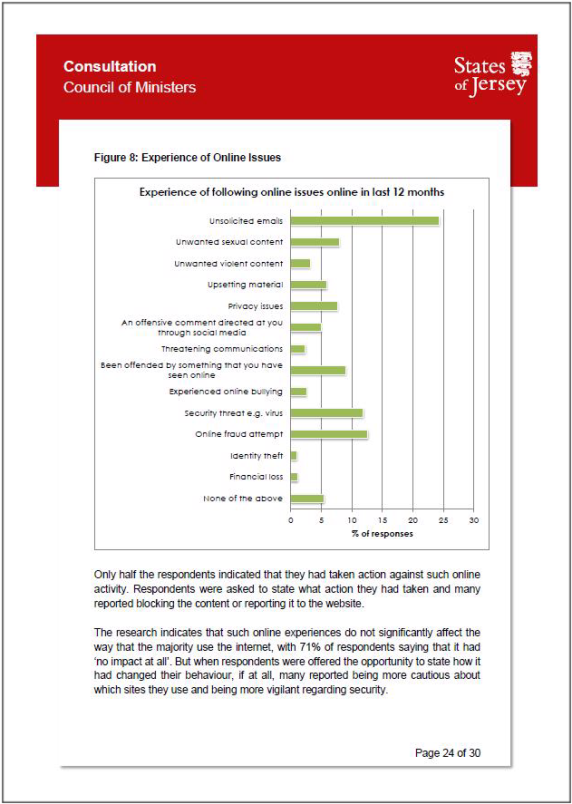

To inform the policy on harmful electronic communications, the Economic Development Department commissioned independent quantitative research to better understand the behaviour and attitudes of online users, as well as their experience of – and existing level of concern around – harmful electronic communications (e.g. cyberbullying). The policy team also examined a range of international case studies. These are described in detail within the consultation document attached to this report as Part 1 of Appendix 2; but in summary, they support the view that there is no gold standard' or single approach internationally, and that the behaviour that this paper considers is often covered by existing legislation that is not primarily aimed at addressing electronic communication (e.g. harassment laws). A summary of the responses submitted to the consultation is also attached to this report, as Part 2 of Appendix 2.

The case studies do demonstrate that some jurisdictions have enacted specific legislation however, or tailored guidelines to address cyberbullying. In the UK in recent years there have been a number of controversial cases in this area that led to concerns about ensuring a consistent and fair approach to prosecution. This led, in 2013, to the Director of Public Prosecutions developing guidelines on the prosecution of cases involving communications sent via social media (the "DPP Guidelines").

In particular, the DPP Guidelines recommend that prosecutors should take into account the intent and context of online communications when considering

prosecuting. The UK guidelines have helped inform the States of Jersey's policy in this respect.

In March 2015, the Council of Ministers (the Council) issued the aforementioned public consultation, based on the findings of the above research, and on the analysis conducted by officers. The consultation sought views on whether it would be appropriate to make changes to the legislation in Jersey applying to harmful electronic communications. Specifically, it sought views on whether the existing legislation should be amended to remove doubt about its application, and to ensure that it is future proof'. It also considered whether a new offence is required to tackle the publication of revenge pornography.

The responses to the consultation mainly offered personal opinion and highlighted individual experiences. As such, they provided limited new quantitative evidence; however, they did support the original quantitative research that was commissioned as part of the development of the consultation, as well as other analysis and evidence gathered throughout the process (e.g. international case studies) (see Appendix 2).

What are the changes to the Telecommunications (Jersey) Law 2002 intended to achieve?

Having undertaken the research mentioned above, it became apparent that the existing legislation in Jersey is, in fact, largely fit for purpose and does provide protection from cyberbullying and other types of behaviour on social media that would be considered criminal if conducted via traditional means of communication. However, the legislation in question was enacted before social media became pervasive, and thus was not designed for the digital era', nor was it explicitly intended to deal with behaviour conducted via social media. The policy view is that some minor amendments are required therefore, in order to –

- ensure that existing legislation applies to harmful electronic communications sent without use of a public network;

- increase the maximum penalties for existing offences which may be applied to electronic communications, to reflect the seriousness of the potential harm to victims of such conduct; and

- ensure that existing offences do not have a chilling effect on free speech, in particular by removing ambiguity about the circumstances in which a prosecution may take place, especially where the sender might not have intended the communication to be grossly offensive or of an indecent, obscene or menacing character.

The amendments were drafted with a view to offering an approach that is light-touch and proportionate, whilst delivering value for money. The aim is not to create new legislation where it is unnecessary, but to ensure that there is the ability to prosecute in all appropriate cases.

In respect of all of the above, it must be remembered that the digital world moves extremely quickly and, therefore, any legislation runs the risk of soon becoming outdated. So far as it is possible to do so, these amendments are designed to ensure the law is future-proof, by which we mean it should remain applicable even as technologies and trends in behaviour change and develop.

This requires the legislation to be platform neutral', which is to say that it must cover all types of electronic communication, irrespective of the device used or the technology that facilitates it. It also accounts for technological development, as well as

for changes in the use of existing technologies, including in ways that may not be foreseeable or commonly practiced today.

The intention is that these amendments to the legislation should not result in a disproportionate increase in the number of prosecutions being brought about. It should be remembered that the existing legislation is largely fit for purpose, and that these amendments are designed to bring clarity to the law and resilience to change. As such, this legislation should not be used to stifle free speech, for example criminalising legitimate political debate and discussion, humour and satire, and restricting people's right to be offensive, etc.

It should be noted that these examples are not exhaustive, and are given for the benefit of States Members, as a means of contextualising the amendments.

How are we going to achieve this?

It is apparent that prosecutions for harmful electronic communications can already be made under the Article 51 of the Telecommunications (Jersey) Law 2002 (the "TJL") or the Crime (Disorderly Conduct and Harassment) (Jersey) Law 2008 (the "CDCJL"). However, there is no room for complacency. Both technology and peoples' behaviour online are changing all the time.

Whilst the consultation process did not highlight any particular difficulties, it would be beneficial to make certain small amendments to the TJL to ensure that single acts of harmful electronic communication, which do not form part of a course of conduct, can be suitably and proportionately punished.

In particular the amendments made to the TJL will –

- Ensure the legislation in this area remains future-proof and platform neutral', the proposed amendment to Article 51 would prohibit improper use of any telecommunications system, not just a public' telecommunications system (such as the telephone network) as it is currently defined. This will ensure that a prosecution can take place where a message of the requisite character is sent over either a private network, or from one device directly to another, for example. It is not to say that this behaviour would not be covered by the current legislation, but that it will ensure there is no uncertainty in the future.

- Ensure the legislation does not have a chilling effect on free speech by making provision so that an offence of sending a message or other matter that is (or conveys anything that is) grossly offensive or of an indecent, obscene or menacing character would be committed only if the sender knew or intended the message to be of such a character or was aware of the risk that the message would be viewed as such by a reasonable member of the Public. The introduction of this mens rea (guilty mind) element of the offence will reflect current practice in the criminal courts, which have drawn on English case law in respect of the equivalent offence in the Communication Act 2003 as persuasive when interpreting the existing Article 51 TJL offence. This element of the new offence has been formulated to clarify the application of Article 51, but allow the courts to continue to draw on English case law where appropriate.

- Ensure fair and proportionate penalties, the proposed amendment to Article 51 would increase the penalty for this offence to a maximum of 2 years' imprisonment and an unlimited fine (either or both of which may be imposed by the court, under Article 13(3) of the Interpretation (Jersey) Law 1954).

It is worth highlighting one further point with regard to acts of revenge pornography (i.e. the non-consensual disclosure of private sexual images). The consultation that

was undertaken earlier this year sought input on whether the Council of Ministers should consider a new offence to deter and prosecute acts of revenge pornography.

Such an offence was recently introduced in the UK in the Criminal Justice and Courts Act 2015, and it carries a maximum penalty of 2 years' imprisonment and an unlimited fine. However, further analysis indicates that this is not necessary in Jersey, and would not be proportionate at this time. It has been demonstrated since publishing the consultation that prosecutions can and have been made under existing legislation for distributing revenge pornography.

Further, it is felt that a new offence tailored to address a specific form of online behaviour would contravene the future-proof' approach proposed by the consultation, in that it would risk becoming quickly outdated, given the pace at which online trends develop.

What are the amendments to the Crime (Disorderly Conduct and Harassment) (Jersey) Law 2008 (the "CDCJL") intended to achieve

Whilst preparing instructions to amend Article 51 of the TJL, it was recognised by the Home Affairs Department that there would also be advantages to amending the CDCJL at the same time, offering additional protection to victims of harmful electronic communications.

To provide some context to this, Article 5 of the CDCJL currently enables prosecutors to apply to the Court for a restraining order where a person has been convicted of harassment. Restraining orders may be drafted to meet the particular risks presented in the case. For example, in cases involving cyber-bullying, the restrictions may prohibit the offender having contact with the victim (by any means online or offline), and prohibit the publication or sharing of any material relating to the victim. The restraining order may be made for a specified or indeterminate period of time. Breach of a restraining order is itself a criminal offence, and carries a maximum sentence of 12 months' imprisonment and a fine.

Restraining orders will be imposed where the Court considers the restrictions necessary (and proportionate) to protect the victim and/or prevent further offences. They play a significant part in managing the risks to the victim and preventing further harassment. However, restraining orders are not available where the offender is convicted of the Article 51 TJL offence, or indeed any other offence. This can leave the police and prosecutors with difficult decisions to make as to how to best protect victims of cyberbullying.

Where a course of conduct can be established, prosecutors will often proceed under the harassment legislation rather than prosecute multiple charges of TJL offences so that a restraining order can be obtained following conviction.

Where a course of conduct cannot be established, but a prosecution could be brought under the TJL, the limits on the availability of restraining orders mean that it may be appropriate to wait and see whether further harassment of the victim takes place that would establish a course of conduct. A prosecution could then be brought under the CDCJL, and a restraining order could be obtained following conviction to safeguard the victim from further harassment. However, given the potential seriousness of even one harmful electronic communication, it was felt that amendments to the CDCJL would be appropriate, proportionate and would avoid the necessity to adopt a wait and see approach in such cases.

Therefore –

- To provide additional protection to victims of harmful electronic behaviour, the amendments made by Article 2 would have the effect of permitting the court to make or impose a restraining order on conviction for any offence (not only an offence of harassment), if the court is satisfied that it is necessary to do so to protect the victim or any person named in the order from further conduct which would amount to harassment, or from a perceived threat of violence.

- It should be noted that restraining orders are available to prosecutors dealing with revenge pornography cases in the UK (whether the prosecution is brought under the Communications Act or harassment legislation).

- To ensure parity with the new penalties under the TJL offence, the penalties for an offence of harassment, and for breach of a restraining order, would be increased correspondingly to a maximum of 2 years' imprisonment and an unlimited fine.

Conclusion

By enacting the amendments described above therefore, the States of Jersey will ensure that people in Jersey are appropriately protected from all forms of harmful electronic communication, now and in the future.

Specifically, the amendments will do this by ensuring that the wording of the legislation in Jersey is future-proof, so that people are protected even as technologies and behaviour change. Further, the amendments will ensure that the specific context of online communication is taken into account, and that an offence would only be committed if the sender knew or intended the message to be of a grossly offensive, indecent, obscene or menacing character. The penalties in this area have also been updated to ensure that they are appropriate and proportionate.

Lastly, the consultation document attached as Appendix 2 to this report provides a detailed background to the policy development in this area (though it should be noted that the final policy position was adopted on the basis of a range of evidence, including the consultation, after it was issued), and human rights notes prepared by the Law Officers' Department are attached as Appendix 1.

Financial and manpower implications

There are no financial or resource implications for the States arising from the adoption of this draft Law.

Human Rights

The notes on the human rights aspects of the draft Law in Appendix 1 have been prepared by the Law Officers' Department and are included for the information of States Members. They are not, and should not be taken as, legal advice.

APPENDIX 1 TO REPORT

Human Rights Notes on the Draft Telecommunications (Amendment No. 3) and Crime (Miscellaneous Provisions) (Jersey) Law 201-

These notes have been prepared in respect of the Draft Telecommunications (Amendment No. 3) and Crime (Miscellaneous Provisions) (Jersey) Law 201- (the "draft Law") by the Law Officers' Department. They summarise the principal human rights issues arising from the contents of the draft Law and explain why, in the Law Officers' opinion, the draft Law is compatible with the European Convention on Human Rights ("ECHR").

These notes are included for the information of States Members. They are not, and should not be taken as, legal advice.

The purpose of these amendments is to ensure that the criminal law in Jersey continues to effectively deter the sending of harmful online communications, and provides appropriate and lasting protection for the public, whilst also ensuring that it does not have a chilling effect on free speech.

The draft Law makes amendments to the Telecommunications (Jersey) Law 2002 ("the 2002 Law") (see Article 1 of the draft Law) and also to the Crime (Disorderly Conduct and Harassment) (Jersey) Law 2008 ("the 2008 Law") (see Article 2 of the draft Law). As the amendments to each of those Laws raise different issues with respect to ECHR compliance, they are analysed separately below.

Amendments to the 2002 Law

Article 1 would amend the 2002 Law to expand the scope of the offence currently found in Article 51 of that Law. The substituted Article 51 would prohibit improper use of any telecommunications system, not just a public telecommunications system such as the telephone network. The purpose of this change is to ensure that the offence applies to communications over private networks, or sent directly from one device to another without the use of a public network (e.g. via Bluetooth).

The amendments made by Article 1 would also increase the maximum custodial penalty for an offence under the substituted Article 51 from a maximum of 6 months' imprisonment to a maximum of 2 years' imprisonment.

Article 1 also introduces an express mens rea' (guilty mind) element into the substituted Article 51 offence of sending a message or other matter that is grossly offensive or of an indecent, obscene or menacing character. Under new Article 51(2) and (3), the offence in Article 51(1) would only be committed if the sender knew or intended the message to be of such a character or was aware of the risk that the message would be viewed as such by a reasonable member of the public.

The principal ECHR right that may be engaged by the amendments made to the 2002 Law is the right to freedom of expression under Article 10, which states, as relevant:

"1. Everyone has the right to freedom of expression. This right shall include freedom to hold opinions and to receive and impart information and ideas without interference by public authority and regardless of frontiers

2. The exercise of these freedoms, since it carries with it duties and responsibilities, may be subject to such formalities, conditions, restrictions or penalties as are prescribed by law and are necessary in a democratic society, in the interests of national security, territorial integrity or public safety, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, for the protection of the reputation or rights of others, for preventing the disclosure of information received in confidence, or for maintaining the authority and impartiality of the judiciary."

The amendments to the 2002 Law made by Article 1 capture additional means of communication and substantially increase the penalty for misuse of a telecommunications system. Therefore the amendments may amount to an interference with the right in Article 10(1) of the ECHR.

The right to free expression is fundamental to the maintenance of a free and democratic society. However, despite the high importance attached to this right, it is possible for restrictions on the right to be justified under Article 10(2) of the ECHR. Any such interference must pursue a legitimate aim set out in Article 10(2), must be prescribed by law and be "necessary" in a democratic society (i.e. proportionate to the aim pursued).

Tackling the misuse of telecommunications systems to send grossly offensive, indecent, obscene or menacing messages clearly falls within the scope of the legitimate aims set out in Article 10(2) ECHR.

The offence in Article 51 of the 2002 Law (now and as substituted), can be applied by the courts in a way that, in the circumstances of a particular case, protects the public while allowing free speech, including rude or distasteful comment or banter, to continue.

The extension of the application of the Article 51 offence to communications sent without use of a public telecommunications system is important to ensure the offence can be applied to new technology and does not change the type of offending behaviour captured. The increase in the maximum custodial penalty for commission of the substituted Article 51 offence reflects that conduct amounting to cyberbullying may have a very significant effect on the victim, particularly in a small community. The increased penalty will give the prosecution and the criminal courts greater latitude to reflect this in sentencing in serious cases.

The new mens rea element of the substituted Article 51 offence has been formulated to reflect the decisions of the courts in England and Wales relating to the application of the equivalent offence in section 127 of the Communications Act 2003 (in particular the decisions in Chambers v DPP [2012] EWHC 2157(Admin) and DPP v Collins [2006] UKHL 40). That case law would be persuasive here in any event, so this addition might not substantially alter the nature of the Article 51 offence. However, it does provide additional certainty and clarity as to the circumstances in which an individual will be liable to prosecution and will help to ensure that Article 51 is applied in a manner that is proportionate in practice.

Taking into account the points above, the amendments made by Article 1 are proportionate to the pursuit of a legitimate aim.

Amendments to the 2008 Law

Article 2 would amend the 2008 Law so as to permit the court to make or impose a restraining order following conviction for any offence (not only an offence of harassment), if the court is satisfied that it is necessary to do so to protect the victim or any person named in the order from further conduct which would amount to harassment, or from a perceived threat of violence. The new Law would also increase the maximum penalty for breach of a restraining order to 2 years' imprisonment and an unlimited fine.

The ECHR right most likely to be engaged by this amendment is Article 8 ECHR, which provides:

"1. Everyone has the right to respect for his private and family life, his home and his correspondence.

2. There shall be no interference by a public authority with the exercise of this right except such as is in accordance with the law and is necessary in a democratic society in the interests of national security, public safety or the economic well-being of the country, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, or for the protection of the rights and freedoms of others."

The imposition of a restraining order may infringe the right to private life under Article 8(1) ECHR of the person on whom it is imposed. However, the imposition of such an order also serves to protect the Article 8(1) ECHR rights of any potential victim of harassment or threatening conduct. Interference with Article 8(1) ECHR rights can be justified where the interference is in accordance with the law and proportionate to a legitimate aim identified in Article 8(2) ECHR.

The imposition of a restraining order following conviction for an offence may pursue a legitimate aim falling within the scope of Article 8(2). Further, where it is proposed that a restraining order should be made, the court will be required to balance competing Article 8(1) ECHR rights to ensure that the extent of any restriction imposed by a restraining order is proportionate. This requirement is reflected in Article 5(4)(b) of the 2008 Law as amended by Article 2(4), which makes it clear that the court can only make a restraining order where it is satisfied, on the balance of probabilities, that it is appropriate to make the order to protect a person from conduct that would amount to harassment or would be likely to cause the person to be in fear of violence.

The requirement for the court to balance competing Article 8 ECHR rights when exercising its powers to make, vary or discharge a restraining order also arises from Article 6(1) of the Human Rights (Jersey) Law 2000. That Article requires the court to act in a manner compatible with Convention rights, including Article 8 ECHR.

Taking into account the points above, Article 2 is also compatible with the ECHR, as any interference with Article 8(1) ECHR rights arising from it will be in accordance with the Law and should only be such as is necessary in a democratic society for the protection of the rights of others.

In view of the above, the draft Law is compatible with the ECHR, as any infringement of the rights in Articles 8(1) and 10(1) is capable of being justified under Articles 8(2) and 10(2).

![]() Explanatory Note

Explanatory Note

This draft Law would make amendments for the purpose of introducing more effective sanctions against "cyberbullying" and other offensive or malicious uses of online social media in particular, and telecommunications in general. Article 1 would amend the Telecommunications (Jersey) Law 2002 to expand the scope of the offence in Article 51 of that Law. The substituted Article 51 would prohibit improper use of any telecommunications system (not just a public telecommunications system such as the telephone network). An offence of sending a message or other matter that is (or conveys anything that is) grossly offensive or of an indecent, obscene or menacing character would be committed only if the sender knew or intended the message to be of such a character or was aware of the risk that the message would be viewed as such by a reasonable member of the public. An offence would also be committed where a person sends a false message or persistently uses a telecommunications system for the purpose of causing annoyance, inconvenience or needless anxiety to another. The penalty for an offence under Article 51 would be increased to a maximum of 2 years' imprisonment and an unlimited fine (either or both of which may be imposed by the court, under Article 13(3) of the Interpretation (Jersey) Law 1954).

In the Crime (Disorderly Conduct and Harassment) (Jersey) Law 2008, the amendments made by Article 2 would have the effect of permitting the court to make or impose a restraining order on conviction for any offence (not only an offence of harassment), if the court is satisfied that it is necessary to do so to protect the victim or any person named in the order from further conduct which would amount to harassment, or from a perceived threat of violence. The penalties for an offence of harassment, and for breach of a restraining order, are increased correspondingly with the change to the Telecommunications (Jersey) Law 2002, to a maximum of 2 years imprisonment and an unlimited fine. New provision is also made for amendment or revocation of a restraining order, on the application of the Attorney General or the person against whom the order was made.

Article 3 would give the title by which this Law may be cited and provide for it to come into force 7 days after it is registered.

DRAFT TELECOMMUNICATIONS (AMENDMENT No. 3) AND CRIME (MISCELLANEOUS PROVISIONS) (JERSEY) LAW 201-

![]() A LAW to amend further the Telecommunications (Jersey) Law 2002 and to amend the Crime (Disorderly Conduct and Harassment) (Jersey) Law 2008

A LAW to amend further the Telecommunications (Jersey) Law 2002 and to amend the Crime (Disorderly Conduct and Harassment) (Jersey) Law 2008

Adopted by the States [date to be inserted] Sanctioned by Order of Her Majesty in Council [date to be inserted] Registered by the Royal Court [date to be inserted]

![]() THE STATES, subject to the sanction of Her Most Excellent Majesty in Council, have adopted the following Law –

THE STATES, subject to the sanction of Her Most Excellent Majesty in Council, have adopted the following Law –

1 Telecommunications (Jersey) Law 2002 amended

- The Telecommunications (Jersey) Law 20021 is amended in accordance with paragraphs (2) and (3), and in those paragraphs a reference to an Article is to an Article of the same number in that Law.

- In Article 1(1), in the definition "message" for the word "means" there shall be substituted the word "includes".

- For Article 51 there shall be substituted the following Article –

![]()

![]() "51 Improper use of telecommunications system

"51 Improper use of telecommunications system

- A person (the sender') who, by means of a telecommunication system, sends a message or other matter that is (or conveys anything that is) grossly offensive or of an indecent, obscene or menacing character, is guilty of an offence if either paragraph (2) or (3) applies.

- This paragraph applies if the sender knew or intended the message to be grossly offensive or of an indecent, obscene or menacing character.

- This paragraph applies if the sender was aware, at the time of sending the message, of the risk that it would be viewed as grossly

![]() Draft Telecommunications (Amendment No. 3) and Crime Article 2 (Miscellaneous Provisions) (Jersey) Law 201-

Draft Telecommunications (Amendment No. 3) and Crime Article 2 (Miscellaneous Provisions) (Jersey) Law 201-

![]() offensive or of an indecent, obscene or menacing character by any reasonable member of the public.

offensive or of an indecent, obscene or menacing character by any reasonable member of the public.

A person who, for the purpose of causing annoyance, inconvenience or needless anxiety to another –

A person who, for the purpose of causing annoyance, inconvenience or needless anxiety to another –

- sends, by means of a telecommunication system, a message that the person knows to be false; or

- persistently makes use of a telecommunication system, is guilty of an offence.

- In paragraphs (2) to (4), message' includes a message or other matter, and anything conveyed by the message.

- The States may make Regulations amending this Article if it is considered necessary to do so to take account of changes in technology, and such Regulations may contain –

- provision consequentially amending or modifying, for the purposes of this Article, an expression used or defined in this Law; and

- incidental, supplemental or consequential provision.

- A person guilty of an offence under this Article shall be liable to imprisonment for a term of 2 years and to a fine.".

2 Crime (Disorderly Conduct and Harassment) (Jersey) Law 2008 amended

- The Crime (Disorderly Conduct and Harassment) (Jersey) Law 20082 is amended in accordance with paragraphs (2) to (5), and in those paragraphs a reference to an Article is to an Article of the same number in that Law.

For Article 3(3) there shall be substituted the following paragraph –

For Article 3(3) there shall be substituted the following paragraph –

"(3) A person who commits an offence under paragraph (1) shall be

liable to imprisonment for a term of 2 years and to a fine.".

- For the heading to Article 5 there shall be substituted the following heading –

![]() "Restraining orders".

"Restraining orders".

- In Article 5 –

- in paragraph (1) the words "under Article 3(1)" shall be deleted;

- in paragraph (2) for the words "in order to ensure that the person will not commit a further offence under Article 3(1)" there shall be substituted –

![]() "for the purpose of protecting the victim of the offence, or any other person named in the order, from conduct by the person against whom the order is made, which would, if carried out –

"for the purpose of protecting the victim of the offence, or any other person named in the order, from conduct by the person against whom the order is made, which would, if carried out –

- amount to harassment of the victim or other person named in the order; or

be likely to cause the victim or such other person to be in fear of violence against them.".

be likely to cause the victim or such other person to be in fear of violence against them.".

For Article 6(2) there shall be substituted the following paragraph –

For Article 6(2) there shall be substituted the following paragraph –

"(2) A person who commits an offence under paragraph (1) shall be

liable to imprisonment for a term of 2 years and to a fine.".

- For Article 7(1) and (2) there shall be substituted the following –

![]() "(1) An order under Article 5 may be amended or revoked by the court

"(1) An order under Article 5 may be amended or revoked by the court

which made the order, on the application of –

the Attorney General; or

the Attorney General; or - the person against whom the order was made.

(2) The court to which an application is made under paragraph (1) may amend or revoke the order if (and to the extent that) the court is satisfied that it is appropriate to do so.".

3 Citation and commencement

This Law may be cited as the Telecommunications (Amendment No. 3) and Crime (Miscellaneous Provisions) (Jersey) Law 201- and shall come into force 7 days after being registered.

![]()

![]() Endnotes (Miscellaneous Provisions) (Jersey) Law 201-

Endnotes (Miscellaneous Provisions) (Jersey) Law 201-

1 chapter 06.288 2 chapter 08.115