The official version of this document can be found via the PDF button.

The below content has been automatically generated from the original PDF and some formatting may have been lost, therefore it should not be relied upon to extract citations or propose amendments.

SCRUTINY PANEL MENTAL HEALTH REVIEW SUBMISSION BY STATES OF JERSEY POLICE (SOJP)

Terms of reference

The panel invites submissions on some or all of the following questions from people and organisations who run or have accessed or used mental health services in Jersey. The deadline is 5pm on Friday, 28 September 2018.

- What are the current trends in mental health in Jersey?

- What progress has the States of Jersey made on implementing its mental health strategy? What further work is required?

- How have mental health services changed since the launch of the mental health strategy in 2015?

- What support is in place to ensure the organisations which provide mental health services are able to work in partnership in the best interests of the individual concerned?

- What are the potential risks and benefits of separating child and adult mental health services? How could any potential risks be mitigated?

- What examples of best practice are available from other jurisdictions that Jersey could learn from?

- The current trends are shown below.

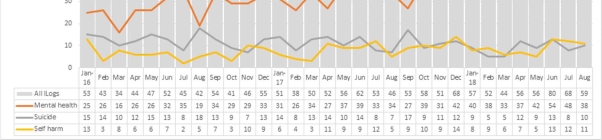

The number of individuals detained in police custody 2016 -2018 (ytd)

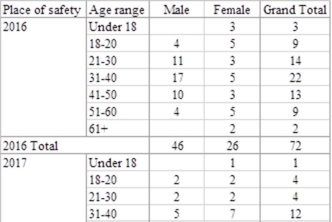

The age range and sex of those detained in police custody 2016 – 2018 (ytd)

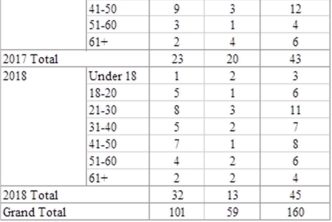

The amount of time spent in police custody 2016 – 2018 (ytd)

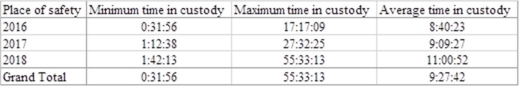

The number of incidents requiring a police response involving mental health, suicide or self-harm

- The Mental Health Criminal Justice Forum (MHCJF) was established in 2015 following the completion of the Mental Health (MH) strategy. The MHCJF was allocated circa £250,000 and an initial business plan developed. Very little progress appeared to have been made and as a result of certain matters coming to a head the SoJP called a meeting with partners on the 1st May 2018 where it became very clear that joint working around MH matters had lost its way. This group has since stopped meeting in favour of needing to refine priorities and a new structure has been put in place. In our opinion the future work required is as follows :

Legal view – A clearly defined piece of work is need to interpret the varying pieces of legislation and guidance in order to provide clarity on roles and responsibilities. At present the subjectivity around such pieces of law and national guidance (NICE guidelines and Authorised Professional Practice) is unhelpful.

Pathways and process maps – Once the legal position is clear, time needs to be invested in mapping out pathways for all eventualities around MH detentions. There is no route map for staff to follow. Once developed, this would provide for a commonly agreed reference point to benchmark what should happen, particularly when there is a professional difference at operational level.

Training – Once the law and pathway is clear training is needed for all staff to ensure the awareness of such guidance.

Development of facilities and resources – Any pathway is likely to highlight the absence of suitable provisions in terms of secure accommodation, an appropriate place of safety suite and resource constraints. Whilst accepting this is likely it may also provide opportunities for workarounds to be developed. Such opportunities have not yet been clarified or capitalised upon.

Conformity - And finally once the above is in place, partners will have an agreed process that will need to be followed. When deviations are made then a culture of learning can be created whereby instances are debriefed and corporate learning can be improved. The hope of course is that in bringing clarity to the process, professional differences will become less and joint working will become much more cohesive.

- The one significant change since 2015, from a police perspective, was the launch of Community Triage. Community Triage was trialled between October 2017 and March 2018. The SoJP invested significantly in trawling data to be in a strong position to assess outcomes from the trial and a health analyst completed a piece of work to overlay shared data analysis. This piece of work reflected an overwhelming need for Community Triage. An extension of the triage was initially agreed but at very short notice was withdrawn by partners in H&SS due to staffing capacity. This meant that agencies had to revert to detentions for assessment being required for cases that could have otherwise been resolved at home and away from the need to formally detain.

- The main obstacles to successful partnership working, which is in the best interests of the patient, are the issues highlighted in questions 2 & 3 above and the lack of provision in terms of appropriate secure facilities and suitably qualified staff to restrain and manage problematic patients as well as an appropriate place of safety suite.

- The SOJP have no strong views on this issue other than there is a need for a service that seeks to cater for all communities and has properly auditable pathways to reflect how different communities can be accommodated. At present, ideally children get routed through the Emergency Department (ED) to Robin Ward as a place of safety and adults go from ED to Orchard House with an overflow to Emergency Admission Unit (EAU). However, the reality is the police often end up with young people and adults in police cells due to inadequate facilities and insufficient resource levels.

- The UK has had a steep learning curve regarding the facilitation of mental health work. The Jersey issues mirror those that were experienced in the UK approx. 5 years ago. The UK has develop "136 suite" type facilities together with great examples of street triage and joint facilities. 136 suites are bespoke health led facilities that are used and tailored to cater for people in crisis and cater for those who are intoxicated, violent or ready to receive that initial assessment.

Following a number of UK forces vocalising similar concerns over many years the UK response has seen investment in such facilities, together with national guidance and agreed protocols being developed, to properly deal with people in crisis. That is exactly what is needed locally but there has been a continuous default position that blames the absence for facilities and resources as to why such work hasn't progressed. Most cities across the UK boast good examples of collaborative working 136 facilities.

Locum staff working in Jersey are regularly surprised by the absence of facilities in Jersey. The default position is that Police and ED staff are often left to use either ED or police cells/facilities as an operational workaround.

NHS Northumbria has initiated bespoke multi service hydra type training services around the workings of 136 suites which would be a good model to follow should we resolve the issues laid out in 2 above.

In summary the UK is a good example of where our focus should be and one that has risen to the challenge of providing suitable facilities for people suffering from mental illness. The Jersey challenge is no different apart from scale but there appears to be a reluctance to develop services to adequately meet the needs of those who need it most – the community. We maintain that police cells should only be used for those suffering from mental health crisis in the most exceptional of circumstances